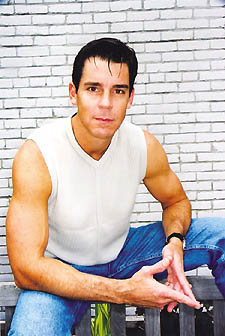

Out of the Park

Former pro-baseball player Billy Bean pursues a new field of dreams

Photos by Michael Wichita

|

Billy Bean may be in the middle of a long and overscheduled book tour, with speaking engagement and signing parties crowding every free minute of the day, but it’s not that hard to find a way to carve out some extra time for, say, a visit with a reporter.

Just ask if he wants to play some early morning tennis. He’ll be up for it.

At 38, Bean still has the earnest, boy-next-door look of an athlete fresh out of college, and when he talks about his love of sports, you can’t help but feel a bit of longing for those little league glory days that may lurk in your own past. His competitive streak is just as apparent — playing a few quick, games on Adams Morgan’s public tennis courts, he plays every point as if it were a tournament. It’s not necessarily about winning, but about playing the best he can, whatever and wherever the game may be.

When Bean left behind his life as a professional baseball player, he let go of a dream he had pursued since childhood. But his life as a closeted gay man had grown too stressful, and he could no longer balance the closet with the clubhouse. As a closeted player, he had divorced his wife and secretly moved in with his first lover, Sam. When Sam died of AIDS, Bean was so frightened of his secret being revealed that he didn’t attend his lover’s funeral.

“Why was it so impossible to think that a baseball player could grieve for a man?” he says. “I just didn’t think I was worth enough to ask, and that sucked. That was a terrible, terrible decision I made.”

Once out of the closet, Bean found himself in love with man who is now his partner, Efrain Veiga. And he found himself the center of attention in a gay and lesbian community looking for ways to break down the barriers of homophobia in sports. Bean is blunt about how strong that barrier remains — he doesn’t foresee any professional baseball player coming out and continuing to play in the near future, a view that has caused some critics to question his commitment to encouraging people to come out.

His new book, Going the Other Way ($23.95, Marlow & Co.), is in part an answer to that criticism — while he hopes for gay players to eventually be as commonly accepted as any other, he also believes his experience shows what a hard road that will be for the one who chooses to take it. Even so, he says his goal is to deliver a positive message for gays and lesbians, and their friends and families.

“This book is not a sad story about a victim of homophobia, or baseball mistreating me,” he says. “It’s about what it’s like to live in the closet and to try to realize a dream under those restrictions.”

METRO WEEKLY: I understand you won the gay tennis tournament in Miami recently.

BILLY BEAN: I did. It was the first tournament that I entered — I just started playing three years ago. I’ve always been a tennis fan, and it was the healing thing I needed to let go of baseball emotionally. It’s not like I left baseball to play tennis, but I love to get out there and compete. When your life is a sport and your job is to get up every day, stay in shape, and be at the ballpark, and then you just stop, your body goes into shock. I played at 195 pounds, and I got down to about 170 pounds. I felt terrible, I didn’t like the way I looked.

[So] instead of playing tennis once a week, I played twice a week. You have to play to get better. Then I met a couple guys and we made up our minds to try to play three times a week: doubles on Saturday, and then singles twice a week. The whole tennis tournament was such a great experience — the vibe from the guys, meeting everyone, the people who wanted to see if I could even hit a ball. I hope to play about three tournaments a year — I’m going to really to focus and see how it goes.

MW: It sounds like you’ve solved that problem with the body shock, so what do you get out of playing sports now?

BEAN: It’s what I love to do. I love to be around sports. You just don’t eliminate something that’s your passion your whole life. I tried to eliminate sports because there was a lot of pain associated with it at the beginning. Now I realize that it’s what I like to do. As far as the book is concerned, it gives me a great platform where I feel comfortable talking about things. I may not be an expert, but I know a lot about sports. It’s a really cool bridge for giving young gay and lesbian kids a positive environment to be in, and to try to create opportunities for them. I hope to be involved in sports for the rest of my life.

|

MW: In the book you talk about the perfectionism and intensity you brought to baseball and other sports. Do you do the same when you’re playing now?

BEAN: Oh, yeah. Yesterday I played great, and today I’m obsessing because I didn’t [this morning]. It’s always going to be a part of my personality. It drives my partner crazy, it drives me crazy, but it’s just the way I am. I feel most comfortable when I have a sense of control over little things, because I know you can’t control life and you have to roll with the punches. I’ve always had that mindset, wanting to get better every day, do something that makes you a little bit better of a person.

MW: On kids and sports, do you think there is less use of words like “faggot” these days than there was when you were a kid? And do you think gay and lesbian kids are feeling any more comfortable playing sports?

BEAN: I think kids now know a lot more than we did. They are more aware that you can’t talk a certain way. But I think when you get in certain environments, it still exists completely — just because people aren’t verbalizing it as much doesn’t mean they don’t believe it. Thirty years ago, we were being told not to run like a faggot, that if you dropped the ball you were a sissy — all these stupid names. The responsibility that I have is to make [sure they’re] taught that you can’t talk like that or treat people like that. It’s not asking a ten-year-old, “Are you a gay kid?” It’s training all kids, [giving them] the proper environment to grow up in.

MW: Did anyone ever direct that kind of “faggot” language at you when you played sports as a kid?

BEAN: When you’re the best player on the team — whether you’re the best player on your tennis team, a gay softball team, or a little league baseball team — you’re treated a little bit special. That doesn’t make it right or wrong. I just seemed to be sort of exceptional in sports. I was a very sensitive kid and if I would have been called something like that I think it would have just devastated me, whether you called me a faggot or a terrible football player, because I yearned to please the coach. I don’t remember it being directed at me specifically. But I just remember hearing it directed all around me.

MW: Is it still common, at least in team sports?

BEAN: Absolutely. In the clubhouse, cocksucker jokes and all that kind of stuff are always in your ear — you can always hear it. If they knew there was a gay person in the clubhouse, they probably wouldn’t say it. But in a million years they never thought that there would be. So, if someone throws at your head, if somebody makes you mad, it’s just like using the “f” word. People get used to saying it and the word “faggot” is just sort of ingrained as a cuss word of comfort when you’re really pissed off at somebody.

MW: Did you ever use it yourself?

BEAN: I think I never used the word like that. I’ve cussed my whole life, just being outdoors and around guys and stuff like that, but I just was always a little bit more conscious of that word. But you learn you have to be careful. Let’s say two guys [from the team] are in the front of the airplane telling a gay joke. If someone in the back chimes in, “Hey, you shouldn’t talk like that,” they’ll both turn around and say, “What are you, gay?” If you raise an issue or make an issue of something, it draws attention to you. When I was playing I didn’t want that attention. So I just kept my mouth shut and put it down to the guys being idiots. Believe me, there’s a lot of stupid behavior going on — it’s not just people bashing gays.

|

MW: So in professional sports is it just a maturity thing?

BEAN: People forget how young pro athletes are — they’re in their early twenties. How much have you grown up in the last ten or fifteen years? Maybe you were mature in your recognition of sexual orientation, and racial diversity and those kind of things, but most of these guys don’t know anything except how to hit a baseball or throw a ball, because that’s all they’ve been doing. It’s like pro tennis players — they’re thrust into the limelight and expected to have this polished vocabulary and have views on certain things, and they’ve been on tennis courts since they were five years old. They live, eat, breathe and drink tennis. Baseball’s exactly the same way. [Sometimes] they have this simplistic view that they’re a tough guy and if you’re not tough it must be because you’re queer.

MW: It sounds like you knew you were different as a kid. When did you start getting a clear idea what that difference was?

BEAN: The first time I felt that something was up was an accidental experience I had in a trainer’s room. I was on the road with my college team. I had a slightly pulled hamstring, and the trainer starts massaging and kneading the muscle. He just touched me ever so slightly, like it would have been if it was an accident — your hamstring is close by there. I got excited and I got an erection, and he just started stroking me right there [on the training table]. It was such a public environment that you would never think that something like that was going on. I wasn’t looking at him, I was laying down, it was sort of exhilarating. It wasn’t a finished sexual encounter, but when I got done I was trembling. I was like, oh my god, I can’t believe I just let somebody do that to me. I’m 22-years old and a senior in college, I’ve got a girlfriend I’m very serious with and I’m thinking, does that make me gay? It just freaked me out a little bit, but it certainly piqued my curiosity. [The team] flew home the next day and I ran home made love to my girlfriend.

After I had been married about two-and-a-half years, I got sent down to the minor leagues in Albuquerque. My wife was back in L.A. and I was alone a lot and feeling pretty shitty. I was going out with the guys a little bit more. [One night] I had about five or six beers and then left. I got in a cab and I just asked the cabbie if he knew where any gay bars were. It was like a little investigative journey. And it was so intoxicatingly scary. I didn’t know what the hell I was looking for. The idea that I was going to reach over and touch somebody, it seemed impossible. It’s kind of embarrassing in the book, because I really had no idea what I was doing.

I was probably not the best or the most giving lover. It was just beyond exciting, but I felt so bad about myself every time I did that. And after a day or two I would start thinking about it again. If I was playing pretty good, I would give myself that little gift, like a window of time and go see what I could do. I never believed that two guys could live together and be happy together. But for me, my whole life changed when I ran into my partner Sam, because I fell in love with him — upside-down, crazy in love. That complicated everything else, because I had a wife, I was a baseball player, and I became very confused. I wasn’t really confused anymore about the physical thing but the emotional part. That was when my life became really, really difficult. It started to erode my ability to be clearheaded at the park, I couldn’t stop thinking about it all the time.

That’s why my book is an explanation of why people haven’t come out [in baseball]. It’s not like an authoritative person is saying “Don’t come out because it’s not good.” It’s just not possible in a player’s mind, at this moment, to exist in a comfortable environment and just play.

MW: When that first openly gay pro baseball player comes along, what special thing will he need to have to make it work for him?

BEAN: They’ll have to have the desire to carry an added pressure that has nothing to do with playing. When you’re playing, there are a lot of things you can’t control, but you can control your discipline and your focus. But this is going to invite a lot of attention that has nothing to do with playing. It’s just easy to foresee. Let’s say Mike Piazza had said, “Yes, I’m gay.” They would be following him home, looking in every place he goes to see who he’s with. After the revelation of a player then they want to know who, what, why, and how. I think a player would think, why did I do this? Why did I complicate my life? It would be an amazing accomplishment for someone to withstand all of that outside pressure and play great. I think it would be really sad if we saw a great player start to recede or fail. We’ve all seen how the media salivated over the possibility of Sandy Koufax or Mike Piazza, so it’s going to get exponentially more crazy if someone does come forward and is playing at the same time. So we have to focus on making the environment better, and keep capitalizing on these great, courageous people who are coming out everywhere else. And hope that pretty soon being gay will be no big deal, which is a dream of mine.

|

MW: Which do you think is more likely: a baseball player coming out of the closet while playing on a major league team, or somebody who is openly gay from an earlier point getting themselves signed to a major league team?

BEAN: It’s probably going to be the latter, unless someone’s outed. The environment is much more comfortable at the high school level now. I think that they would be sort of hardened and ready just from being out to their family and friends and schoolmates. Then maybe we would have a chance to rally around that person and make sure that he has a fair opportunity. Because if it happens at the big league level, they’re going to be in a little bit of shock at the beginning. I’m telling you from experience, the amount of attention I got was unbelievable, and I wasn’t even playing anymore. It was a little scary. You immediately become a political person, just because you’re representing a large community. It’s a lot to ask from someone who’s just a baseball player.

MW: Why did you want to publish a book?

BEAN: I kept finding I was having trouble talking to my parents about what happened. After the story came out there were a lot of gray areas about how my partner died, why he died, and how that affected me. It was very scary for them. I don’t think it matters that I’m gay or straight, but I don’t like talking about sex with my mother. I wanted to sit down and write a letter to her, and it kept getting bigger and bigger.

Also, I had been speaking for HRC and I did a show for Arli$$, and [afterward] people were misconstruing my politics about coming out and living an open and honest life. I really felt frustrated and hurt by it, because I had generously opened up my life. I don’t make money doing that, it’s not like it’s a lifestyle or livelihood. I felt that it was my responsibility to go out there. The book allows me to say in my own words what I believe and don’t believe. I’m not telling people not to come out. I live out, I’m an example of being open, everyone knows who my partner is, my life has improved in every way. All I have done is give an explanation — from my own experience — of why baseball players haven’t done it yet. Because by the time you get to the big leagues, you’ve dedicated your life to it. I don’t know how many people would dedicate their lives to a career and then be willing to throw their career away. You have to respect people’s privacy, and everybody’s time and place is different. We don’t all start from the same place. If your only obstacle is telling your mother, that can be just as important as being a big league ballplayer not telling your teammates. My life isn’t more important than yours, and yours isn’t more important than mine. So the book has been a big project, and I put my heart and soul into it, but I feel this release of pressure to explain myself, and that’s nice.

MW: What is your job in Miami?

BEAN: Efrain and I used to own a couple of restaurants, and we sold those. Now we buy properties, renovate them and resell them. I like it a lot more, because we have a wonderful network of friends and business relationships. Efrain is a very creative person, and I manage things well and I’m organized. So we’re doing the same thing but we’re not doing the same exact work. I feel like things have really come around for me.

MW: When you’re working with clients, do you ever have moments where you think, “God, I wish I were playing ball again?”

Advertisement

|

BEAN: [Laughs.] About ninety-five percent of the time. It was very hard for me to accept that I walked away from my career. I loved being a baseball player. I don’t think I’ll ever feel so great about my own accomplishments as I did when I was paying center field in the big leagues. It’s fun to run out to that position and hear your name on the scoreboard and go up to bat. A lot of people would like to be doing that. So sure, I think about that all the time. But I know I have a great life, I have a great partner, I have wonderful friends that I never allowed myself to have before. I’m so excited that I still get giddy sometimes. Life gets better each day. The book really was a nice therapy for me, to finally get out all that stuff about letting go of the game and my partner Sam. I feel a real burden’s been lifted.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!