Signature Moments

Paris Barclay talks about the Vietnam War, gay marriage, and the fabric of hate

“My mother won’t explain it,” says Paris Barclay of his offbeat but memorably elegant first name. “She claimed she was reading mythology when I was born, but I’m not so sure I really believe that. My name is just the weird one in the whole family.”

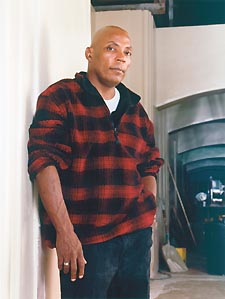

Mrs. Barclay must have known that out of seven children (six of whom had “normal names” — like William, Neal, Mark and Brian), her son Paris was unique, a man destined for extraordinary achievements. At 48, the Harvard-educated Barclay is an up-and-coming composer, an established Emmy-winning television director and a strongly opinionated columnist for The Advocate. He’s currently aloft on his own cloud nine: his most treasured project — One Red Flower, a musical based on the bestselling 1985 book Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam — has finally come into full bloom with a magnificent world premiere production at Arlington’s Signature Theatre.

Barclay |

Barclay has been working on the project since the late eighties, and it’s gone through an astounding (some might say perfectionist’s) twenty-four drafts to get it to the stage as it is now.

“It’s never been shown in this particular form,” he says. “There are new characters, new songs. [Signature Theatre Artistic Director] Eric SchaefferÂ… [helped to] develop it into a finished piece.

“Other people have attempted to direct it,” he continues, “and they’ve done jobs that have varied from okay to just awful. Eric has taken it to a whole new level. It’s just much more moving and the production is as professional as I’ve ever seen. It’s not trivial, it’s not superficial, it’s deep and extremely well-accomplished.” Given the underlying political nature of the work — and its unspoken correlations between Vietnam and the current situation in Iraq — Barclay couldn’t be more thrilled that it’s making its debut in the nation’s capital.

“I wish I could have a Congress night,” he says, noting that several invitations have gone out to congressmen and other high-level politicians. “Some are coming — I’m not going to reveal their names — but we really need everybody to come. Then they would see the impact of their decisions on the fighting man, because Vietnam is a great mirror of that.”

Barclay has no delusions when it comes to One Red Flower ever hitting the Great White Way.

|

“I don’t think One Red Flower is going to be a Broadway musical. I don’t think the audience that goes to Broadway wants to be taken up this trip because it’s a tough trip — it’s not a frolic. I mean, you’re going right into the psychology of these guys in a very intimate way. It’s just not going to be what the tourists are going to run and see when they’re on vacation.”

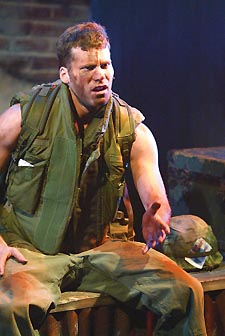

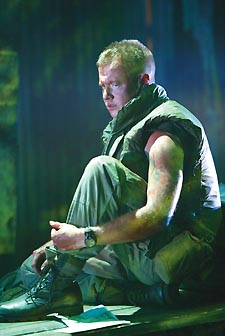

Barclay, who is gay, is currently at work creating a potential dramatic series for Showtime. Called Hate, it deals with the hate crime unit of the New York City police department and stars the Oscar-winner Marcia Gay Harden, who spent several years at Arena Stage, and Jeremy Davidson, who stunned local audiences with his dynamic, spectacular turn in the one-man show, Nijinsky’s Last Dance. Barclay is secretive about details — understandable, as the show still hasn’t been shot (he’s calling from location scouting in Toronto) — but promises that if Showtime picks Hate up, the resulting series will be uncompromising and edgy. “I like things with strong flavors,” he says with a chuckle.

Hate will include plenty of gay content. One Red Flower, on the other hand, contains none. Still, Paris is quick to rise to its queer defense, claiming — in slightly self-mocking terms that only a fellow gay man could appreciate — “But the actors do have their shirts off.”

METRO WEEKLY: You’ve been working on One Red Flower since 1986, and have gone through twenty-four drafts before getting to this point. What was it that inspired the project?

PARIS BARCLAY: I’d just finished a musical called Almost a Man, which was done at Soho Rep in New York. I was a little depressed and I said, “What would be a good subject for a musical? I’m going to find one today.” I walked into the Coliseum Book Store — a great bookstore on 57th Street, it’s not there anymore — and just wandered around. This new book had come out called Dear America: Letters Home From Vietnam. I’m always interested in letters because they’re so personal and direct. So I opened the book and the first poem in it was so beautiful that I started to tear up in the bookstore. Bought the book, went home, wrote music for the poem before I did anything else — I still have the recording I made of it. Then I read the rest of the book.

MW: Is the song still in the show?

PARIS: It’s the last song — “If You Are Able,” a poem by Michael Davis O’Donnell. He was a helicopter pilot.

MW: How has the show evolved over the drafts?

PARIS: Originally it was more of a quilt of different soldiers’ perspectives on the war through the early ’60s to the end of the war. And it was very presentational. It didn’t have continuing characters and the songs were basically the poems and actual letters written by the soldiers set to music as directly as possible. Different actors would play a number of different soldiers and you’d get the whole experience of the entire war through their letters.

Over time, that just became unwieldy. Eventually we decided it would be better if there were only six characters. So I adapted and adjusted and edited the letters to basically create six composite characters that went through one year in Vietnam.

MW: How much of the piece is drawn from the letters?

PARIS: Ninety-five percent. It’s exactly what the soldiers wrote during the time. The only time I would change anything is if they had to refer to each other, because they didn’t refer to each other in the letters. Each of the six main soldiers was primarily based on one letter writer. I would take what I called a “spine” letter writer and build other letters around that person so that they would be further developed.

MW: What did you learn during the experience of putting it all together?

PARIS: For me, it was a total education of what the Vietnam veteran really went through in the war. I was only thirteen in 1969 so I knew what was going on but wasn’t as educated as I’ve since become. And what I’ve learned is there were a lot of soldiers there who had really good reasons for fighting — honorable reasons, reasons that I, looking back, find very moving. A lot of it was patriotism, a lot was that they believed very much what their government told them and they trusted that government. So they went to war. Then when they got there, in many cases they became disillusioned and lost faith in the process. That to me was extremely dramatic because it provided a natural arc for characters, so you could really see them grow and develop over the years.

MW: It seems like a perfect time for the work to premiere, what with the situation in Iraq.

PARIS: When people come to see it now — and I haven’t been to the previews [at Signature] yet — I understand the audience’s response has been extraordinary, that they have been described as “leaping to their feet” after it’s over. I think that may have something to do with the fact that they recognize that [we’re going through] the same story all over again. Some of the questions that the soldiers had during Vietnam [are similar to those of the soldiers in Iraq]. One soldier talks about being “extended endlessly” in not being able to actually predict when he’ll come home. One soldier talks about watching the abuse of a prisoner where a Vietnamese woman’s head is pushed under water; he’s disgusted by the whole process. Another soldier talks about how they’re here to defend these people against terrorism. Those things hit you like cold water because it’s 1969 and they’re talking about Vietnam, but the same things are happening again. So it’s actually stunning that the show has finally come to its finished form right when we’re in a crisis period of the Iraq war.

|

MW: You had originally wanted to only be a composer.

PARIS: That was the idea. While I was at Harvard I wrote thirteen musicals and plays, and I wrote the music for The Hasty Pudding Show. I was always interested in writing music and I thought that was what I would do. It’s only because I couldn’t make a living at it that I sort of segued into advertising, and then writing commercials, and then directing commercials, and then directing music videos. Before long I was directing television shows. It just sucked me up. It certainly wasn’t the intended career path — I thought I was sort of going to be the black equivalent of Stephen Sondheim.

MW: You still could be.

PARIS: I’m getting old.

MW: Still, you’ve had a great career in television directing. ER, NYPD Blue, The West Wing are some of the best shows on television.

PARIS: But those shows are very different from musicals in the theater. If I had my druthers and could actually afford it, I would just work in the theater all the time because it’s such a different experience. It’s certainly entertaining and challenging to do something like The West Wing but it doesn’t compare to the thrill I get out of seeing One Red Flower done.

MW: What did you win your two Emmys for?

PARIS: Both were for NYPD Blue. One was for an episode called “Lost Israel Part II,” where a millionaire was molesting his son and eventually murdered him and tried to blame it on a homeless man who couldn’t speak. The second time I won it for Jimmy Smits’ final episode in which he died.

MW: What’s it feel like to win an Emmy?

PARIS: It’s better than a sharp stick in the eye. [Laughs.] It was interesting winning it two years in a row. The first year I was overwhelmed. The second year I felt it had more to do with the writing and the power of Jimmy Smits’ performance than it had to do with me. He just broke our hearts and I think that’s what [the Emmy voters] thought had to do with the directing but it really had much more to do with how the episode was constructed and how it was performed by Jimmy.

MW: Not long ago you worked as a director on Fast Lane, which was cancelled by Fox after its first season.

PARIS: Yeah, one season, boom. It was great eye candy. There’s a place for that superficial stuff, especially on television, but you can’t necessarily expect it to last.

MW: I remember a time on television when the networks would at least give something a chance to catch on. These days it seems if a show isn’t an instant hit, it’s instantly cancelled.

PARIS: Well, [the networks] will let a reality show gain an audience and build because it’s so much cheaper to produce and they are primarily the owners of it. Someone did a survey that showed the reality programs in the first season with low ratings last longer than the dramas and the comedies, which are pulled immediately because they’re much more expensive. Reality shows without those pesky unions and those pesky actors are a lot cheaper.

MW: Does that concern you as a director?

PARIS: Absolutely. I’m praying that it’s actually a fad and that in the next few years people will want and hunger for real stories being told. One of the reasons I’m working in cable now is because network television is so obsessed with reality. They’re beating it totally into the ground.

MW: Tell me about the project you’re working on now.

PARIS: It’s a pilot for Showtime called Hate about the Hate Crimes Unit of the New York Police Dept. It’s set in New York and it’s going to be pretty edgy. Marcia Gay Harden plays the head of the unit and Jeremy Davidson — who is familiar to the Washington audience because he was just at the Kennedy Center as Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof — plays a bisexual cop who comes on the force and wreaks havoc.

MW: Do you think there’s an audience for it? I mean, is the weekly dramatic dose of hate crimes perhaps too much for a television audience?

PARIS: There’s an audience for CSI. I don’t know if you ever watch CSI, but it deals with lots of pretty gruesome things and that hasn’t stopped 25 million people from tuning in every Thursday night. So I think that there will certainly be an audience at Showtime. People like what people like, and it’s not always what the network is offering.

MW: I’m assuming you’re planning to include all forms of hate crimes, including those committed against gays.

PARIS: Absolutely. It deals with a wide variety of intolerances. The New York City Police Department counts a hate crime as a bias against any person due to their ethnicity, their color, their religion, their perceived ethnicity, their disability, their age or their gender.

MW: How overtly are you dealing with the Jeremy Davidson character’s sexuality?

PARIS: I don’t want to spoil it for you.

MW: Spoil it just a little bit.

PARIS: Well, we’re dealing with it pretty directly from the pilot episode on.

MW: Does he have a male lover?

PARIS: [Laughs.] I can’t tell you that — you’ll have to watch the show. Well, first, the show has to get on because it’s only a pilot. Showtime can still decide not to make it. But should Showtime decide to make it, by episode three you’ll know a lot more.

MW: Your sole film project thus far was Don’t Be A Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood, which I have seenÂ…

PARIS: Good lord, you’ve seen it? I’ve tried to keep people from seeing it. I really would rather not talk about it. All I’ll say is I would never do it again — it’s just not what I’m about. It’s so much work to do a movie and I really want to do things I care about and really be proud of, things that have some sort of impact on society. I don’t want to spend that much time doing something that frivolous.

With One Red Flower — to come back to that, for example — I just know that it’s changing peoples’ point of view. I know that it is both entertaining and educational and so I feel like I’m really contributing something to a world that can be torn down so easily. Why should I be another voice for negativity? It seems worthless. I don’t want to do that.

MW: Let’s discuss your childhood.

PARIS: Well, I was a poor black child, one of seven children, and for most of my life lived in a small house in Harvey, Illinois, a mixed, lower middle-class suburb [of Chicago]. I got a scholarship to go to a private all-male boarding school in Indiana — it was called the La Lumiere School for Boys and I was the first African-American student there. That changed my life. That’s when I started writing music and was involved in the Choral Club and all the other stuff.

MW: How did the other boys at the time respond to your arrival?

PARIS: Well, you know, it’s Indiana. It was northern Indiana which is not as bad as southern Indiana but because it was a Catholic school and because they really wanted to have kind of a diverse student body, I was supported. But I also spent a lot of time being very alone and I felt apart from things — separated even more because of being black than because I may have potentially been gay. Eventually, I overachieved to make up for it and became the number one student in the class.

MW: When did the gay thing set in?

PARIS: Set in?

MW: Sorry, but I’m so tired of asking people “When did you come out?” that I’m trying to find new ways to say it.

PARIS: [Laughs.] I like that. “When did the gay thing set in?” Well, it wasn’t really a big question for me. I mean I’ve had a lot of relationships with both men and women in my youth and I probably didn’t really identify as gay until late in college. That’s when I had my first real boyfriend. Since then I’ve pretty much said, “That’s the way to be, man.” Besides, if you’re going to work in musical theater, being gay is a credential that’s really helpful. There aren’t that many straight musical composers.

MW: I take it, then, that being out hasn’t been a hindrance in your career.

PARIS: I think it’s been helpful in an odd way because I am an out gay writer-director as opposed to a closeted gay writer-director. As I’ve often said when I talk to my directing class, “Why don’t you just be out, because if you’re out, the people who want someone who is gay will call you up and that will be nice. And the people who don’t want someone who is gay won’t call you up and that’s good because you don’t really want to deal with them anyway. When you’re not out, you could get into a lot of sort of heinous situations where it could be used against you and you could be with people who hate you and they don’t even know it. But if you’re out, they just won’t even bother. They’ll just cross you off the list in the privacy of their own offices and you’ll never be called.”

|

MW: You’re fairly politically outspoken, particularly through your regular column in The Advocate. What do you think about the whole marriage issue?

PARIS: A few years ago, I wrote a whole column about “Why Marriage?” and I still stand by it, even though it’s not the most popular opinion, which is that this is not the time to have this fight. We really didn’t have all our ducks in a row before we went forward with it, and because it just happened everyone said we couldn’t turn back the clock, that we were making a move and we had to make it now. But the audience wasn’t prepared for it. And by that I mean the masses of public who were not ready for this issue. Part of this is because those of us in entertainment haven’t done anything about it. We haven’t educated the audience. Will & Grace, which is a perfect vehicle to teach people about gay marriage, hasn’t touched it. Queer Eye for the Straight Guy — just because you see those guys flitting around doesn’t mean that you believe in gay marriage.

Entertainment has always preceded the social movements and taken responsibility for educating people, and we just haven’t done it. So now it’s like cold water and people are going to resist it. I think it’s going to set the movement back. In the next year we’re going to take some big losses on this issue because we went ahead too far too fast.

MW: There was like a viable window of opportunity.

PARIS: It seemed like a window was opened. But the window wasn’t really opening and we hadn’t really defined the terms. Marriage is a word that is wrapped up in the Judeo-Christian ethic — we hadn’t defined it our way yet. The religious right — they basically own the word — have used it against us and it’s very convincing. If I were in charge of the world, I would have delayed this until John Kerry was elected and until we had done more education in entertainment and movies to show what loving couples could be about. We haven’t done that. We haven’t even done a little cheesy TV movie that shows a real gay marriage.

MW: As an African-American gay man, what is your feeling toward those who equate the gay civil rights movement with the civil rights movement of the sixties?

PARIS: I feel that if we really believe in civil rights, just as Jesse Jackson was always saying with the Rainbow Coalition, we believe in them for everybody and that’s that. End of story. It actually irritates me when people are upset about the parallel as if, in some way, it cheapens the black civil rights movement.

To have true equality for all men and all women in the United States means everybody. It doesn’t mean you pick and choose your constituency. I get furious when people get furious about it, like “It’s our precious movement, don’t compare it to you fags,” which is basically what they’re saying. And I’m saying [to them] that “You don’t really believe in civil rights. You just believe in getting yours — and that’s a whole ‘nother thing.”

MW: HRC recently said that it would not support ENDA legislation if transsexuals were not included in the bill’s language. Some people have said that HRC’s position is an ENDA-killer. What are your thoughts?

PARIS: Well, I hate to say it, but I have to support HRC. It’s just like what I was talking about with civil rights — you can’t have it halfway. If we’re going to include people, we have to include everyone who is in it. I know it’s kind of a minority within a minority, and a lot of gay people look down their noses at transgenders as if they aren’t part of our movement, but you know, if they are people who are discriminated against, people that we have a relationship with, then we should put them on our list of people that we’re going to go down with.

If we’re in a fight with transgendered and bisexual people and if you’re not happy with that, then once again, it’s all about you, isn’t it? Together we’re more powerful than we are individually, so I want to bring those ladies and men right on.

MW: It’s always been interesting to me how the discriminated against can so easily discriminate themselves.

PARIS: It is. It’s amazing how within groups hatred is so strong. I know a lot of gay people who are totally afraid of transgender people. It freaks them out and they are very uncomfortable. “Transvestites are bad enough but transgender, oh, my God, I don’t know what to do! I have no transgender friends. I have nothing in common with them.” To me, that’s just another form of racism. I try to beat that back as much as possible, but our capacity to hate is enormous.

MW: Have you ever been the victim of a hate crime?

PARIS: Yes, in Boston. I made the mistake of coming out of a gay bar that happened to be in South Boston when I was a kid at Harvard, and I was beaten by a couple of kids who looked like they were military kids on a leave. They beat me fairly bloody. I managed to pour myself into a cab that was gassing up at a gas station. I didn’t have any money and the cab driver took me back to Harvard Square and didn’t charge me anything. I got cleaned up and never went to that bar again. But the lesson is that there are horrible, negative, evil people in this world and then there are cab drivers who will get you safely to where you are going for nothing. That’s the balance of the world. And I want to be on the cab driver side if I can.

Paris Barclay’s One Red Flower runs through October 3, at Signature Theatre, 3806 S. Four Mile Run Drive. Tickets are $30 to $49 and are available by calling tickets.com at (800) 955-5566 or (703) 218-6500 or by visiting www.signature-theatre.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!