Inside Man

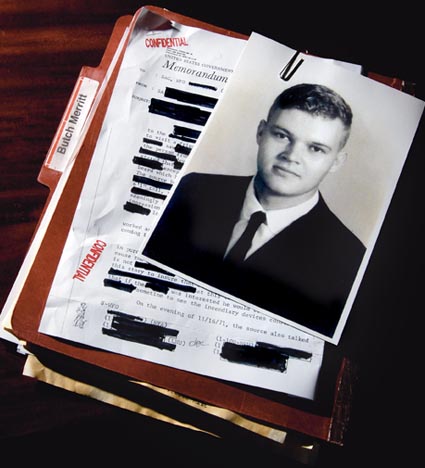

Butch Merritt was a leading spy in America's homegrown cold war against homosexuals

Earl Robert Merritt Jr., a.k.a. Butch Merritt, claims humble beginnings outside Charleston, W.Va. Had he remained in West Virginia, it’s nearly certain his life would have been quite a bit simpler than the path he took to Washington as a young man, not long after President Kennedy was assassinated, though he says his move was prompted, in part, by sexual abuse at a Catholic high school he attended.

A few years after landing in the nation’s capital and coming out as a gay man, Merritt says he was recruited by Carl Shoffler of the Metropolitan Police Department to spy on the District’s GLBT community in a time of simmering civic discontent, anti-war demonstrations and COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program), the acronym for the FBI’s effort to spy on Americans.

Having accepted his mission from Shoffler, who would go on to make a name for himself in history as the MPD detective who arrested those breaking into Democratic National Committee offices in the Watergate in June 1972, Merritt weaves a tale full of the fantastic. After all, says Merritt, he’s the one who tipped off Shoffler, now deceased, to the Watergate break-in two weeks before it happened.

Merritt’s recollections, included as snippets here and there in various books and articles, might be easily dismissed, were it not for the crate full of documents he secured following a Freedom of Information Act request for his ”file.”

While the paperwork deals largely with Merritt’s more mainstream work — spying on the ”New Left,” the Weathermen, the Institute for Policy Studies — there are also bits specific to the gay community, such as his tip that the Gay Activists Alliance, precursor to the Gay and Lesbian Activists Alliance, was planning a protest at the Iwo Jima Memorial in January 1972 after police pulled off an anti-gay sting operation in the area. Thanks to Merritt’s tip, U.S. Park Police were ready, arresting six protesters for not having the proper license.

It’s Merritt’s tales not in the file, however, that raise one’s eyebrow highest. A gay man working at the Columbia Plaza Apartments listens to switchboard calls and befriends American Nazis in the building? That Merritt had a source in this particular building, which sits by the Watergate and plays a role in the infamous break-in, seems convenient. That the building also housed Nazis who would befriend a gay man is harder to believe. Then again, search Google for ”Columbia Plaza Apartments” and ”switchboard,” and one returned link is to a 2007 blog posting by ”Haman” on the white-supremacist Stormfront.org page:

”In the late 1960s, when I was with the National Socialist White People’s Party, I once shared an apartment with someone who wasn’t in the party,” writes Haman, regarding a topic that has nothing whatsoever to do with Watergate. ”At the time, we were both working at the Columbia Plaza Apartments as evening desk clerk/switchboard operators, a job that frequently goes to men in the Washington, D.C., area because of the high crime rate.”

And Carl Rizzi of The Academy of Washington, a decades-old association of female illusionists, says Merritt’s Columbia Plaza contact, James Reed/”Rita Reed,” was a member in years past, though his whereabouts today are unknown.

Looking for verification of events now nearly 40 years old is tricky, but one nevertheless stumbles into this sort of reinforcement again and again. There is, however, also the blurring that comes with time.

Frank Kameny, founder of the D.C. branch of the GAA, doesn’t recall the Iwo Jima protest, though he says that’s something his group would have done. Nor does he have a solid memory of Merritt.

”The name rings a very loud bell,” Kameny says of Merritt. He adds, however, ”If someone said that we were being surveilled, I don’t think anyone would’ve expressed surprise. It was a different era, of course, in many ways.”

Kameny speaks from experience, having been fired from the Army Map Service in 1957. Homosexuality could bar federal-agency employment till 1975, when the Civil Service Commission issued amended hiring guidelines.

Today, Merritt considers himself bisexual and lives in the Bronx with his wife, Debbie. Stories past, such as his claim to have targeted then-closeted Watergate attorney Douglas Caddy, float around in various books, periodicals and Web postings. More recent stories, such as his working as an informant for New York City Police, have also seen print. But, says Merritt, he is far from celebrated. He’s seen the inside of more than one jail, recovered from a crack-cocaine addiction and today suffers from various medical conditions.

”I’m 63 years old. I have a heart condition. I have a back condition that I think entitles me to a prognosis of perhaps four or five more years to live and that’s it.”

He wonders aloud if people in the gay community in D.C. might resent his betrayal.

Deacon Maccubbin, owner of Lambda Rising, on whom Merritt says he spied, is not scornful.

”I am sure that had I known what he was doing at the time, I would’ve been very angry,” says Maccubbin. ”With the hindsight of 30 or 40 years, pity is probably the best word to use.”

Neither can Kameny muster much outrage: ”If what he said is truthful, I think he was contemptible. But that was what things were then…. These things go back to simply ancient history, which is gone.”

METRO WEEKLY: You look very clean-cut in your archival photo.

EARL ROBERT ”BUTCH” MERRITT JR.: That’s the way I was raised: very clean-cut. I was very shy, very bashful. I was an introvert who overnight became an extrovert.

MW: From your experience at the Catholic school?

MERRITT: From the Catholic experience and from the fact I was experiencing gay life. I was confused, frustrated. There was no such word as ”gay” when I was coming out.

MW: How did you avoid military service?

MERRITT: I was 4-F. The group I was in, everybody was chicken. We’d go to a psychiatrist, pay $25 for a letter that says you’re homosexual, take it to the draft board, and that was it. I remember taking my letter in and giving it to the woman a the draft board and she chastised me, saying, ”Humph! This is nothing to be proud of.”

MW: Then it was off to D.C. to join the Civil Rights Movement?

MERRITT: Yes, because in West Virginia we had a lot of rednecks who didn’t want integration. And I was a rebel. I jumped on the bandwagons of different things.

MW: Did you fit in here?

MERRITT: I did. I don’t know how, but I did. Just the civil-rights stuff. Every demonstration Dr. King had, I was at.

MW: Did you find work?

MERRITT: Yes. I found work at Children’s Hospital as a post-mortem technician.

MW: Where were you living?

MERRITT: At the Envoy Towers. The property manager, also one of the owners, gave me an apartment free for six months because he liked me. [Laughs.] I was continuing to be prostituted, I suppose. He helped me get the job at Children’s Hospital.

MW: So you settled in well. You were more liberated in D.C?

MERRITT: Oh, yes. Once I got away from West Virginia, I discovered that I wasn’t the only [gay person] in the world, and that there were bars and other people to identify with.

MW: Do you remember which bars you frequented?

MERRITT: [A] Ninth Street grill, I think was one. That was very close to the FBI Building. And one by the bus station, the Brass Rail. Bobs-Inn on 14th Street, Nob Hill, Georgetown Grill.

MW: How did it evolve from there to becoming a Police/FBI informant?

MERRITT: I moved out of the Envoy Towers — I was there for several years — but I discovered Dupont Circle, the park. There was quite a diversity of people. I decided to take an apartment in that area, 1818 Riggs Place. Then, my most popular address, 2122 P Street. I had an apartment there in the alley.

I was living in Dupont Circle, hanging out with an unusual group of people — I’d never met drag queens before. One was Christine Keeler, real name Gregory Sewell. Another was Rita Reed — his name was James Reed. He was one of my sources during Watergate, unknowingly. He worked as a telephone operator at the Columbia Plaza Apartments beside the Watergate. He used to listen in on phone calls there and feed me information.

I had friends in the gay crowd, the drag-queen crowd. I also had straight friends in the hippie crowd. The communists were hanging out there. It was just a diversity of everything in Dupont Circle at that time. The circle used to be jam-packed, 24-7, with people in all phases of life, political to sexuality, everything under the sun. I used to hang out there.

Anyway, there was a hippie — long hair, blue eyes, maybe a couple years older than me. He made very good friends with me, nothing sexual. I’d never had a straight friend before like him, who was so genuinely nice. We became very best of buddies. His name was Carl Shoffler. He turned out to be Detective Carl Shoffler.

Carl came one day and showed me his badge and he said, ”I’m a cop, Butch. I don’t mean to deceive you, but we’ve been profiling you. I was asked to profile you.” He said, ”We need someone to work this circle, to work this whole area, because everybody that you know are communists, anti-American, un-American, and they’re involved in overthrowing the United States government, the presidency of the United States” — Nixon at the time — ”and they’re all planning this huge, anti-war demonstration.”

He said, ”Since you’re 4-F” — he already knew that much, I never told him that — ”then you can do something red, white and blue patriotic for your country since you didn’t serve in the military, by working for us in an undercover capacity.”

Reluctantly, I did allow myself to be recruited. I guess I sort of believed him at the time, because I was very politically stupid, naïve — as I am today, I suppose.

MW: When was that?

MERRITT: I’d say probably May of 1970.

MW: What were your reservations?

MERRITT: First of all, believing that the people I knew were such a danger to the United States of America. I was a hillbilly. We thought that everything was all red, white and blue in this country: the United States Constitution, civil rights, flags waving and all that good stuff. What he was telling me was just so to the contrary, I was in total disbelief.

MW: But there were some small acts of domestic terrorism at the time.

MERRITT: Yes, I did find out that. [Shoffler] was able to influence me gradually by showing me pictures of people I was associating with who had criminal records, who were being watched by the FBI. He showed me their records. It started to make sense that maybe I was wrong in my judgment and that some of these people were extremely dangerous to our government.

Then again, looking back, with all these people I used to hang out with, I’m not sure if there was one, even one…. I know there were some people very closely associated with the Weatherman group, and I know they bombed [various sites]. The thing is, none of these people were gay.

[Shoffler] was telling me one of the heaviest movements in this country was the gay people, that they were coming out.

MW: Shoffler recruited you primarily to spy on the gay community?

MERRITT: He started with that. It escalated very quickly. He knew what he was doing. He was working in the Third District as just a regular detective — robberies, rapes, murders, that sort of thing. Then he escalated from that to the intelligence division. He was also working hand-in-hand with the FBI counterintelligence, COINTELPRO. At the same time, I was working for all these agencies, unbeknownst to me.

MW: Shoffler was your primary contact?

MERRITT: Yes, and he gave me a number, which was SE003. I used to amuse myself, ”How did I get to double-0 three and James Bond got to double-0 seven?” I asked him what ”SE” stood for, and he said, ”special employee. I used that number to pass information and also to get paid.

MW: How much of the surveillance work you did was on the gay community, specifically?

MERRITT: Oh, a vast amount. They gave me cameras to take pictures of people in the park, on the streets, in the bathrooms, at the P Street Beach in the woods. They also had other plants out there besides me to set [people] up, such as dropping my pants and them taking pictures.

I started with the gay groups as fast as they would come up: the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), Mattachine. Carl [Shoffler] wanted me to tell the police and the FBI stories like, for example, the GLF commune house — I think that was 1620 S St. NW — that they had Molotov cocktails in the basement. None of that was true. I was only in that house two or three times in my whole life. I was never past the hallway, the living room. I had no idea what their kitchen or their basement looked like.

MW: Did the GLF guys seem militant to you?

MERRITT: No, not at all. In fact, I went on demonstrations with them. They made this paper pamphlet, maybe a single piece of paper folded over, and on the cover in big letters: ”Are You One Too?”

In a little caption, it said, ”The person handing you this is a homosexual.” It was trying to get people to come out of the closet. We handed them out in front of — I don’t know, the Justice Department? Somewhere downtown.

But those were the stories they wanted me to pass on to make them look like dangerous radicals, that the GLF was a militaristic, gay, revolutionary group.

MW: So that’s what you reported?

MERRITT: I did. It’s not fun for people who lived through that era and who have files placed on them from me. Whether they like me personally, I don’t frankly care one way or another. But if it wasn’t me, it would have been someone else gay in my shoes, I’m sure.

MW: The files show your handlers had a particular interest in The Furies, a lesbian publication.

MERRITT: Oh, yes. The Furies, the Blade — the Gay Blade then. Martina Morgan was the name I used to infiltrate women’s groups to get publications and meeting places and all that mailed to me. They were considered just as radical as the male groups.

There were literally over 3,000 gay names turned in [to the Metropolitan Police Department], [names] I had submitted and then they asked to be spied on.

MW: Three thousand names?

MERRITT: Three thousand names, right.

MW: How did you collect them?

MERRITT: Easily: anti-war demonstrations, protest signatures, signatures from gay organizations to congressmen or senators about gay rights. I simply stole the original petitions.

The petitions were carelessly left around, places like the Community Bookshop, 2028 P St., I think. They even had a little flower shop there on the corner of 20th and P, across from the little bathroom at Dupont Circle called Third Day. All these petitions were placed in these places, so it was easy for me to just go in, steal them and walk out.

I would say that a lot of signatures on the lists, of course, were not always gay. The hippies, the leftists, were normal. They would sign the petitions quickly.

MW: You were just feeding the machine, so to speak?

MERRITT: Exactly. But when the FBI and the Police got a hold of these petitions, they were put down as subversives, as homosexuals, and they did not distinguish who was gay or straight.

MW: Who were good sources of information for you in the gay community?

MERRITT: Well, there was James Reed, who would go by his drag name, Rita Reed. He worked at the Columbia Plaza Apartments on the switchboard and he used to listen in on phone calls. When he gave me information, he did not know he was feeding me information. He was just gossiping with me. We were very, very close friends, and he used to tell me how he loved to listen in and gossip about people’s private business.

He listened in on one group and befriended them, involved with American Nazi activities and had bombs. He told me about little bombs that they had. I said, ”Bring me a couple,” and he did. I handed over the bombs to the FBI.

MW: You also said you had advance knowledge of the Watergate break-in.

MERRITT: I’m giving you the only piece — or one piece — I’ve been holding back. I’ve got to answer you in vague terms, but I knew about it two weeks ahead of time through someone who was, I found out later, a very close associate of Carl Shoffler.

I passed the information on to Carl. He was unaware of it, even though the person who told me knew Carl very well. He came to me the very next morning after spending the whole night through booking his prisoners and he says, ”Butch,” he hugged me and shook my hand, ”you did it. You gave me the best information ever. Don’t ever talk about this.”

MW: Aside from reporting on people, you say you were also an agitator, provoking police.

MERRITT: Oh, yes, absolutely. At demonstrations, I’d be the first one to throw the rock at the cop and hit him. At almost all demonstrations, that was my priority. I had a reputation as being an instigator, a provocateur.

MW: Your handlers, Carl Shoffler, knew you were gay, but that was okay?

MERRITT: I not only had a blessing, I had a license. I could do whatever the hell I wanted to do and nobody could stop me. I could go shoplifting — I used to shoplift at People’s Drugstore all the time. Anytime I wanted to activate my sex life, I’d just simply go in the woods and do it, and there was no fear of the cops.

MW: Do you have any message for people reading this, some of whom you likely reported to the MPD or the FBI?

MERRITT: I am sorry for what I did, from my heart, I really am. Of course they can point a finger of blame at me, because I am the instrument who did these things. I don’t blame them if they love me or hate me. I’m sure a lot of people I hurt are very much alive like I am, and will live to see me in my grave. But the finger of blame should be upon the government. It should be upon the ”big brother” who is watching you.

They’re not going to stop the secret agencies, like the police, the FBI, military intelligence, CIA and National Security Agency until they start digging into their files: ”I want my file. I want my file! And I want it now!” That’s the message that’s got to get across: Get your file. And why is it there? And when they start suing left and right, and inundating our court rooms with individual and class action lawsuits throughout the entire nation, that is when it will change, not until.

If they think I’ve been involved in their lives, they can contact me. If I remember a name, an event, I will help them. There are 3,000 people out there somewhere and they can’t all be dead.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!