Congressional Ties

As the first out transgender Capitol Hill staffer, Diego Sanchez has complicated – and sometimes competing – objectives

by Chris Geidner

July 14, 2010

”Being sometimes the first transgender person in their workspace – openly disclosed as trans – is an important part of what it is that we need to achieve, member by member, staffer by staffer,” Diego Sanchez says.

Diego Sanchez

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Sanchez was born into a military family where the values of respect and standing up for yourself – and the importance of hierarchy – were key. After moving from Panama to Georgia at the age of 7, Sanchez continued on that path, through the University of Georgia and into the upper reaches of corporate America. Starting at public-relations giant Burson-Marsteller in New York City, Sanchez eventually worked for the Coca Cola Company, ITT Sheraton and Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, where he rose to be the global vice president of communications and diversity.

It was there, when presenting a diversity plan for the company that included ”gender identity” and ”transgender,” that Sanchez was told by the head of human resources to remove the additions.

”I can’t take that out. I would be taking myself out. I’m not taking myself, as the vice president of diversity, out of our diversity statement. No. No.”

With his father very ill in Georgia at the time and the company in a period of change, Sanchez left Starwood. At 41, he took the year off, in part to spend more time with his ailing father.

One of his father’s wishes for Sanchez during that last year was, ”After I die and after you finish dealing with my estate, I want you to work in nonprofit for five years. You’ve done global stuff, you know how to introduce brands and products. So what? You have no idea what your skills do as far as how they affect human lives.”

And so he did, working at the Justice Resource Institute on LGBT health issues, including the TransHealth Program, and then at AIDS Action Council in Washington and AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts in Boston. But when Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.) called in late 2008, Sanchez – who had worked on projects in Massachusetts with the out gay congressman since moving to Boston in 1991 – packed up and came to Washington.

Sanchez joined Frank’s legislative team at a time when having a transgender staffer was certain to raise eyebrows – as often from the members of the LGBT community who were suspicious of Frank’s actions regarding transgender inclusion in the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) as from co-workers in other offices on Capitol Hill.

Nonetheless, Sanchez is here, providing a voice for Frank across his district and the country, for the LGBT community throughout the halls of Congress and – at 53 and still pushing forward with gusto – for himself.

METRO WEEKLY: Let’s begin with how you got to D.C.

DIEGO SANCHEZ: I took a train on Jan. 4, 2009. I was supposed to start working on the 6th – on Tuesday – the first day of the 111th Congress – but because I have no sense of direction, I took a dry run. I dressed in a suit, went over to the office, and Barney walks out and goes, ”Oh, good thing you’re here. There’s a hate-crimes meeting today. You need to go to it for us.” And then he says, ”Wait, you’re starting tomorrow, right?” He tells his chief of staff, ”Change his start date to today.” Then [to me], ”Go to that hate-crimes meeting. Nice suit.” And then he walked back into his office.

MW: What did coming here mean to you?

SANCHEZ: I’ve never really sat back and thought in depth about the meaning because I’m focused on trying to make sure my contribution has integrity with the community; that it meets the obligations of my employer, Congressman Frank; and that my participation is actually contributing to our causes and not being a detriment. I’m mindful of remembering that every day I represent him, our community and myself. That is the triad that I operate under.

MW: When faced with a conflict in that triad, what do you do?

SANCHEZ: The points where I have to step up the communications are usually with the community, but it’s only because they don’t have the parallel experience. They just haven’t had to walk that line of being quiet against a storm and to just have the courage to strike when the iron is most hot. Not everybody can do that. Not everybody should do that. We need people to misfire and step out too soon because it’s all progress.

Everything we do is a political statement. Our capacity to go to work is something that our community is having to fight for – the right to work. Our ability to walk down the street in the dark and get to our homes and then get out the next day is a statement about our life – but it’s also what our community has had to fight for to battle hate crimes. Every time I turn the key in the lock and walk in, I know that I’ve made it home safely. And I remember how many services I’ve gone to in the District over the past 10 years for people here that didn’t make it through that night. And I know that I did. I think about that a lot – about what a gift it is just to survive.

The challenge and the burden for our community and its people, for people like you and me, is to get past the “survive” and stretch for the “excel.” If we fall a little short sometimes, it’s okay because we’ve still progressed. And that’s kind of how I look at my role on a daily basis professionally. I’m in a chess game, and I know that I don’t have the luxury of being tired.

MW: A chess game?

SANCHEZ: An example might be before I worked for Congressman Frank, when we had the ENDA challenge in 2007 – “the debacle,” as it’s called. [H.R.] 2015 had gender identity, as well as sexual orientation. And the recollection is more of people thinking that the desire was to have [a bill] only with sexual orientation.

I knew that if Barney could get a bill that was fully inclusive done, he would have done it. I know that. I’ve known him for more than 20 years, [and] I believe that. Barney knew something that other people who have an opinion about this don’t, and that is how the narrative works when you’re getting people to support a bill.

The question is ”What do you want, and what can you get?” And so there’s the gap between those two, and that’s where that triad of ”Who is Diego?” has to do a reality check every day. I understand what people want. Then, my job becomes to listen to all the voices and figure out what we can get and support the best minds as we try to get what we can. Movement isn’t always optimal – but movement is movement. You don’t get to climb every highest mountain with the first effort.

I feel strongly that we’re going to be all right with ENDA, that we’ve got clearly enough support to pass the bill even right now and we’re almost there to defeat the motion to recommit that would limit gender-identity inclusion. We’re almost there, and I’m hoping that it still comes up this year. I don’t know whether it will. I can’t predict that. But I know Speaker Pelosi has talked about her personal commitment to it. Congressman Frank is still doing whipping. He can do many things at one time, and he was working on ENDA at the same time that he was driving this historic financial reform for our country. That just says a lot to me, so it continues to inspire me and it still gives me hope.

MW: Frank inspires you? Some would say that’s complete bullshit, when we haven’t gotten a vote on ENDA – and the last time we got a vote it wasn’t inclusive.

SANCHEZ: I’m inspired because he’s stayed strong, he has been totally focused on trying to get more and more support, [and] he’s been very clear about what he’s asked the community to do. I don’t expect every layman to understand what it takes to change a legislator’s mind, but I do hope that people in our community understand that Barney Frank knows how lawmakers think and what it takes to make them support things.

It’s easy to say, ”This is what I want, and anything shy of that is not acceptable.” But, to me, that is parallel to saying, ”I would like a steak dinner every night,” and only being able to have ramen. You’re still fed. I’m not saying that life has to be a series of packets of ramen, but I am saying that there are days when you have to consume enough ramen to have the energy to be able to purchase that steak. We have started from absolutely nothing, and we have moved some of that.

MW: That fact that you, specifically, are in Frank’s office is a statement. Some people think it’s more a statement to the community than to Congress or anyone else. Do you think the congressman has learned from your presence?

SANCHEZ: I have seen growth, but not over the past year. I’ve seen that growth over the past 20-plus years. From a time when I was at a Greater Boston Business Council meeting about 15 years ago, seated at a table with Congressman Frank, and I talked to him about inclusion, in terms of bills. And he said, ”There will be a time. This is not the time.” That could have been seen as a dismissive brush-aside, but he said, ”When it’s time, I will be there to do it.” And he’s doing that.

He is at our table every day, and I honestly believe that sometimes familiarity may breed a little contempt. That because they know his first name and his last – and they call him by his first more than his last – people think that they know him and what he should do better than he. I disagree with that, with all due respect, to anyone who thinks that they know what Barney should do better than he. His years and decades of service to people who continue to choose him makes that clear.

The statement is an invitation as well, though. There’s room for plenty more, and I would hope that “first” means soon there will be “next.” It would be great to have more openly trans people serving on Capitol Hill. There are plenty of highly skilled people who would be just fantastic.

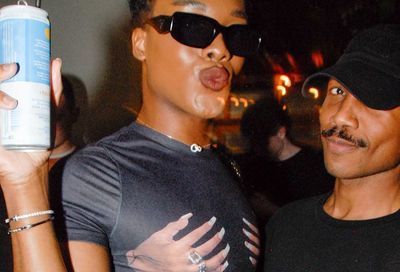

Sanchez

(Photo by Todd Franson)

MW: Despite moving around as a child, you’ve spent much of the past 20 years in Boston. What was Boston like 20 years ago?

SANCHEZ: The thing about the LGBT community in Massachusetts as you started moving through the ’90s to the 2000s – we all knew marriage was going to come before we were going to worry about trans people’s nondiscrimination. But, the promise was made. The decision about how [the gay and lesbian leadership] wanted marriage to look, at the time they were just convening, was that they really didn’t want trans people to be visible. They didn’t want us at the marches. They didn’t want us visible around this topic because there was – and I won’t call it transphobia – but it was a fear of trans visibility. That’s the most generous but also the most, honestly, reflective way that I can say it. I was welcome to come in the door, but not with a list of things. ”You can be here. Your job is to keep your people away from this thing we’re gonna do because the TV cameras are going to be there.” Honest to God, that’s what it was like.

But after marriage, the entire community shifted its focus and has been coming together for a nondiscrimination bill that affects gender identity. That is a difference between how it was and how it is. The environment itself has shifted.

And I know, if I was 20 years old right now, I wouldn’t care about that history, because ”What do I care? I wasn’t even born at that time.” But for people who actually were part of the change that has brought this around, I can’t ignore it, because I lived through that other time.

In the same way, on issues of race, I can’t ignore the fact that I was raised in Panama first and when we moved to Georgia when I was 7 years old, I was not allowed to swim in public pools because I wasn’t white. My reality was … someone looking at me could decide whether I had access to something. Those kinds of lessons are not something I would wish on people who are young today. I hope they never have to experience that kind of door-closing, because it takes its toll on what it takes to build the kind of self-confidence we all need to do the hard battles.

MW: You started out in Panama but spent most of your youth in Georgia – far different than the places you’ve lived as an adult.

SANCHEZ: Growing up in an area where I was on military bases or at the beach, I had not ever come across people who actually judge others simply because of who they are, so it was emotionally tough. My parents had prepared me for it by doing the thing that you wish that every parent would tell a child. ”You’re not better than anybody else” – I was told that – ”but no one is better than you. Everyone is the same. You should be respected, and you should respect.” Those core lessons were early ingrained.

I missed out on things because I told my parents I was born wrong when I was 5. And my mom brought out the Life magazine with Christine Jorgensen on it. She just said, ”I don’t know if there are other people like you. But I know that this person was born a boy, grew up to be a man, became a woman, and that’s harder. So by the time you grow up, it should all be fine.” So my parents kind of dually socialized me so that I learned lessons that I needed for whatever I did.

I didn’t get to do some of the things I would have done if I were born male. I got to play football, but only touch football when it was both sexes. And I was quarterback. But I didn’t get to play junior varsity. I didn’t get to sweat and throw up like all the football players got to do – and I wanted to. I played tennis – but, thankfully, I didn’t have to wear a tennis dress, because that would have been emotionally very difficult. I didn’t participate in those slumber-party things because they didn’t feel right because, ”I was a boy, and I can’t be going to the sleepovers with the girls.”

I started looking at sex-reassignment surgeries when I was 18, and none of them were quite right back then. So I just was like, ”I’m not going to do this now. Maybe some of my friends will become surgeons, and then they’ll do it right.”

MW: Did that make it challenging to get through your early corporate years?

SANCHEZ: Clearly, I was not pretty when you looked at me as a female. It was not pretty. There were dress codes at the time. I had to learn to walk in heels. It was painful. Pantyhose. Skirts. Never makeup stuff. ”I am not going there.” I knew that I was so invisible.

I grew up in a military family where everybody had uniforms, so I could emotionally survive it by treating it like a uniform. I was that person who, at five o’clock – or six or 10 p.m. – whenever I left work, I would totally change clothes before I would leave my office. I’d have jeans or khakis. The heels were first to go.

MW: So you started out the corporate world in heels?

SANCHEZ: Very small ones. I really could not walk in them. If I could have sawed half of it off, it would have been better. The difficulty with that is you know you’re being seen differently than you are. And I was definitely masculine presenting. I could not make a dress look good. I could not make a woman’s suit look good. It just wasn’t going to happen. Even as I started hormones and surgical interventions, I still had to wait until I could do everything to change to be able to fully disclose. So I just sort of presented as someone who was masculine – not yet male – born female. By my mere presence, people understood, ”Oh, he must be part of that part of the community.”

It’s so funny because during recess [on the Hill] most people don’t dress up. For the first six months or so I’d still wear a suit and tie, and my friends were like, ”Why are you wearing a tie?” I’m like, ”Do you know how many years I have to make up for?” All those years that I worked and couldn’t wear one? It was like the one thing – I would wear a suit, a men’s suit, but I couldn’t wear a tie because the tie, to me, was the barrier breaker. To me it felt commensurate to dropping your drawers. ”Look! Surgeries!”

But it didn’t necessarily seem that way to other people. There was this friend, Mike, who was our HR director [at ITT Sheraton], and he used to be like, ”Why don’t you dress up that suit?” I explained to him, ”I can’t wear a tie until I’m ready to do all this disclosure. There’s something about that to me that’s huge. And you can never go back.”

One day we were opening this cigar bar at the Sheraton in Boston. I had a suit on. I had these great ties that I’d gotten in Rehoboth – had one in my coat pocket. Mike is like, ”You know, you could wear a tie here.” And I said, ”Mike, I actually have a tie.” I pulled it out of my pocket. ”Look at this sharp tie! This is a helluva tie!” I put it on and I didn’t have to look back. I was taking a stand, saying, ”I’m a man like you’re a man.”

I didn’t think I could survive it, corporately. I was wrong, because it turned out just fine.

MW: Your story seems to be one of survival and moving beyond survival. That’s what others say they want, too, but they are disappointed in the pace.

SANCHEZ: I understand how young people get frustrated and disillusioned and want things to be neat and comfortable. I totally understand that. I remember myself being the same way. And we survive it all. That’s the lesson: However it works out, it’ll be fine.

We’re on the right track to get a lot of things done. It’s interesting to me that so many of us, when something good happens, sometimes we say, ”That’s really something. That’s really nice.” But too often it’s questioning the motive or whatever the gain is and calling out a shortcoming instead of even taking a second to use it to energize yourself toward the next victory.

I tend to look at what the victory really is, then I can read what all my friends say and recognize all the shortcomings. And then I know what we can work on together to make it even better. And it’s okay. You run out of energy if all you do is expend negative energy. You just run out. I don’t want anyone in our community to run out of energy. We need more energy, not less, and we need good energy, not sour feelings about our own achievements – because we have some, and they’re laudable. We’ll get more. We’ll get more. Every day.

MW: Yeah, looking around at this year’s LGBT Pride Month reception at the White House, it seemed to me there was very intentional trans inclusion.

SANCHEZ: I realized that I was standing as one of four generations of trans men. We took a photograph where it was myself, and [Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition Executive Director] Gunner Scott as the next generation, and [Special Assistant to the Assistant Secretary of Labor] Dylan Orr as the next, and then the young 17-year-old from St. Louis. It was really fascinating to be able to capture that at the White House. It was phenomenal.

Would I have guessed that 10 years ago? Absolutely not. Would I have guessed it four years ago? Six months ago? No. And that’s my point: Our community is still capable of achieving good surprises. You don’t have to be able to see it for it to become real. And it’s not a Pollyanna-ish thing, it’s just my reality is making me recognize that some incredible things happen. You just have to have your eyes open every moment to capture them.

MW: How would you best describe transitioning from your point of view?

SANCHEZ: You walk in looking like one thing, but really being another. You have to be silent at first because nobody walks in going, ”Yes, I’m trans!” You go through this period of time where you have to figure out the language and gauge the safety. And then you tell people something that you know they don’t believe. And then you’re telling them that you’re like them, and they really aren’t comfortable with that. That’s what transitioning is like.

When I tell people that, a lightbulb goes off and they are able to start figuring out how they can help people feel safe and served and respected and alive and not to want to have to do something that harms themselves. And that’s why I stay inspired. I hear Barney make explanations like he did in the hearing last year about ENDA. He said something like, ”I know some people are uncomfortable with transgender people.” He’s just stating what’s true. And then he says, ”You know, when I realized I was gay, I was uncomfortable with myself.” It was humorous, but it was also very real and it gave people room to come to him and go, ”I’m glad you said that, but help me walk through this.” It wasn’t making a judgment about trans people. It was making a window for people who whisper among themselves but needed a way to talk.

I see people changing every day. A couple of the Capitol Police had seen me on TV. One of them told the other one, ”You know, he used to be a girl.” And so, one of them came up to me and goes, ”One of our officers thinks he saw you on CNN. Have you ever been on CNN?” I’m like, ”Yes, I was on Wolf Blitzer yesterday.” ”So, did you used to be a girl?” ”Well, I looked like one. I wasn’t one. I was just born into a girl’s body, but I had to fix that because my brain told me I was a boy. So I told my parents, and they didn’t throw me out and through my life I’ve been able to bring everything in alignment. I’ve been able to fully align my body and my brain to be the way that I’ve always seen myself, but now you get to see me that way too.”

That’s the statement. If Barney had not brought me in, that couldn’t have happened. And [those police] vote, and they have relatives. And you know they’ve told everybody they know. You know they have.

Two Men Charged in Connection with Cecilia Gentili’s Death

Antonio Venti and Michael Kuilan were charged with distributing drugs that led to the death of transgender activist Cecilia Gentili.

By John Riley on April 3, 2024 @JRileyMW

Two New York men have been charged with drug possession and distribution in connection with the death of Cecilia Gentili, a prominent New York-based transgender activist.

The arrest was announced in an April 1 news release from the office of Breon Peace, the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York.

"Cecilia Gentili, a prominent activist and leader of the New York transgender community, was tragically poisoned in her Brooklyn home from fentanyl-laced heroin," Peace said in a statement. "Fentanyl is a public health crisis. Our Office will spare no effort in the pursuit of justice for the many New Yorkers who have lost loved ones due to this lethal drug."

Alabama Republicans Want Trans Space Camp Employee Fired

After the father of an 11-year-old girl complains, Alabama Congressmen demand the firing of a Space Camp transgender employee.

By John Riley on March 18, 2024 @JRileyMW

Several Alabama Republicans have demanded the termination of a transgender employee at Space Camp, arguing that their presence poses a danger to participating students.

Space Camp, an educational program on the grounds of the U.S. Space & Rocket Center museum in Huntsville, Alabama, provides residential and educational programs for youth on topics such as space exploration, aviation, and robotics.

The center hosts approximately 26,000 youth annually, with specific programs for different age groups.

One of those programs, "Space Camp," primarily serves children aged 9 to 11. It seeks to balance educational, classroom-style learning with hands-on activities and entertainment offerings.

Dawn Staley Defends Trans Athlete Participation

The coach of NCAA champion South Carolina women's basketball team shares her opinion on trans athletes ahead of big game.

By John Riley on April 8, 2024 @JRileyMW

University of South Carolina women's basketball coach Dawn Staley grabbed headlines this past weekend when she weighed in on the side of allowing transgender athletes to participate in sports.

On April 6, the day before her Lady Gamecocks were to play in the NCAA Division I "March Madness" Tournament Championship game against Iowa, Staley -- who freely offers her opinion on any topic, regardless if her comments may offend some people -- was asked about her position on transgender athletes competing in women's sports.

The question came from Dan Zaksheske, a reporter for OutKick, a website with a strong conservative viewpoint that markets itself as an "everyman" alternative to mainstream sports news outlets.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

The Magazine

-

Most Popular

George Santos, Duped by NAMBLA Prank, Exits Race for Congress

George Santos, Duped by NAMBLA Prank, Exits Race for Congress  Conservative Ad Makes Case for Transgender Rights

Conservative Ad Makes Case for Transgender Rights  California Mayor Recalled After Coming Out as Transgender

California Mayor Recalled After Coming Out as Transgender  For Don Mancini, Chucky is So Much More Than a Killer Toy

For Don Mancini, Chucky is So Much More Than a Killer Toy  GLOW's Secret Garden Is An "Escape...With A Chill Vibe"

GLOW's Secret Garden Is An "Escape...With A Chill Vibe"  Ralph Fiennes and Indira Varma Soar in STC's 'Macbeth' (Review)

Ralph Fiennes and Indira Varma Soar in STC's 'Macbeth' (Review)  Grindr is Being Sued for Sharing HIV Statuses

Grindr is Being Sued for Sharing HIV Statuses  'The Human Museum' Puts the Bots in Charge (Review)

'The Human Museum' Puts the Bots in Charge (Review)  Win Tickets to "Webster's Bitch" at The Keegan Theatre

Win Tickets to "Webster's Bitch" at The Keegan Theatre  Judge Blocks Ohio's Anti-Transgender Bans

Judge Blocks Ohio's Anti-Transgender Bans

'The Human Museum' Puts the Bots in Charge (Review)

'The Human Museum' Puts the Bots in Charge (Review)  George Santos, Duped by NAMBLA Prank, Exits Race for Congress

George Santos, Duped by NAMBLA Prank, Exits Race for Congress  Grindr is Being Sued for Sharing HIV Statuses

Grindr is Being Sued for Sharing HIV Statuses  Judge Blocks Ohio's Anti-Transgender Bans

Judge Blocks Ohio's Anti-Transgender Bans  D.C. Courts Pop-Up Businesses Ahead of WorldPride

D.C. Courts Pop-Up Businesses Ahead of WorldPride  Cher to be Inducted in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

Cher to be Inducted in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame  Texas Governor Wants to Ban Trans People from Being Teachers

Texas Governor Wants to Ban Trans People from Being Teachers  For Don Mancini, Chucky is So Much More Than a Killer Toy

For Don Mancini, Chucky is So Much More Than a Killer Toy  LGBTQ Teen Sues School Over Suspension For Rap Lyrics

LGBTQ Teen Sues School Over Suspension For Rap Lyrics  California Mayor Recalled After Coming Out as Transgender

California Mayor Recalled After Coming Out as Transgender

Scene

Metro Weekly

Washington's LGBTQ Magazine

P.O. Box 11559

Washington, DC 20008 (202) 638-6830

About Us pageFollow Us:

· Facebook

· Twitter

· Flipboard

· YouTube

· Instagram

· RSS News | RSS SceneArchives

- "We use cookies and other data collection technologies to provide the best experience for our customers. You may request that your data not be shared with third parties here: "Do Not Sell My Data

Copyright ©2024 Jansi LLC.