All of Us

Us Helping Us pushes forward with expanding scope, respect for its roots, and celebration of the whole human being

There are different ways to mark the anniversaries of Us Helping Us, People Into Living Inc. Bishop Kwabena Rainey Cheeks formed the organization in 1985. Incorporation followed in 1988. Other years brought other milestones, such as purchasing a building to call its own in 2001, and actually moving in after all the renovations in 2005.

When it comes to fighting HIV/AIDS, however – particularly in the District of Columbia, and particularly when much of the focus is on African-American gay and bisexual men – anniversaries are rarely occasions to celebrate. More often, they’re simply thorns pricking a community to remind them that the epidemic continues. It may look different than it did when it began, but it continues. The same can be said of UHU.

(Photo by Todd Franson)

”Over our more than 20 years, we have become a much more comprehensive agency,” says Ron Simmons, who has served as the organization’s executive director since 1992. ”Back in ’88, we only served HIV-positive, black gay men. Now we serve HIV-negative, black gay men. We have a transgender drop-in center. We serve youth. We started doing testing for heterosexual women as well.

”At the same time, we are still keeping our focus, our commitment to improving the lives of black gay men – those infected and those who are not.”

Talking with Simmons, it’s clear that’s not as simple as it might sound. There are changes in pharmaceutical technology that have been a blessing for those infected with HIV, while data indicates that black men who have sex with men continue to be hit harder than their peers of other racial demographics. Those realities combine with the day-to-day adaptations that affect any organization. Simmons says UHU has tried to stay on top of all it with ongoing plans, whose spans are becoming shorter to keep up. These days, he says, a five-year plan can’t really adapt quickly enough.

”We’ve had four- and five-year plans. Right now we’re in the middle of a three-year plan,” says Simmons. ”But even three years tends to be too long. Reality changes so quickly. Social media has become much bigger than it was in 2008, 2009. No one would have predicted it would be as big a part of our culture. Now we have to include that in our plan. We’ve gotten funding recently from Kaiser Permanente to do just that. In a year or so, [post-exposure prophylaxis] might become real. No one thought of that three years ago.”

While looking at a Twitter account for UHU or wrestling with a pharmaceutical strategy that may work like HIV-exposure ”day after pills” are all in day’s work for Simmons as executive director, that day’s work is always a juggling act. But UHU is juggling as fast as possible, with these comprehensive plans as short and efficient as they can be. Simmons laughs at the idea of paring down to two-year plans, explaining that the cost of hiring a consultant to survey clients and staff, having the board meet for days to consider the plan, and all the rest that goes into crafting a plan veers into futility once you get shorter than three years. Instead, the juggling must continue.

The latest ball thrown into the mix is alarming. Simmons points to relatively new data out of D.C. (and elsewhere) indicating an alarming crack in HIV-prevention strategies. For whatever reason, that crack is exposing black gay men to HIV at a highly disproportionate rate than other gay men. The data is on UHU’s doorstep, answering the question, ”What?” The ”Why?” however, is far more elusive. Waiting for a definitive answer is a luxury the community cannot afford.

Ken Pettigrew

Kenya Hutton

Karen Giles

Sharlene Miles

Shawn Spencer

Ernest Walker

”When we looked at the details of the last surveillance study, it was pretty alarming,” says Simmons, pointing specifically to a study from the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services published in the October 2010 issue of AIDS Patient Care and STDs. The matter-of-fact title sums up what Simmons and UHU are facing: ”Elevated HIV prevalence despite lower rates of sexual risk behaviors among black men in the District of Columbia who have sex with men.”

”Something we’re looking at now – also not part of the plan – is initiating a national conversation on the paradigm shift in HIV infection among MSM,” he says, explaining that the conventional wisdom of less-risky sexual behavior leading to less risk of infection is no longer so simple, according to the data. ”At first you say, ‘How is that possible?’ These same men were reporting more condom use and fewer sex partners. Chicago found similar results.

”We have to rethink a lot of things. We look at this as definitely something we need to be part of in the beginning. Just increase condom use? It’s got to be more than that. Gay men need them and use them, but that’s not working for black gay men. I don’t have the answers. We only identified this last month.”

Answers or not, Simmons and his staff are compelled to deal with what’s been put in front of them.

As UHU has carried on over the decades, not all developments have been disheartening. The aforementioned advances in HIV/AIDS medications, for example, was a very welcome turn, particularly by Simmons himself. While he played a large role in giving the organization its holistic identity, meeting the first generations of HIV medications with skepticism, Simmons has shown himself to be an adapter rather than a zealot. When his wisdom and experience say change, he changes. And after weathering HIV for nearly two decades on a holistic path – once a pillar of the UHU platform – Simmons did not allow that approach to good health to go from tool to dogma. He adapted in late 2002, starting a pill regimen, and brought UHU with him.

”The medications that were first out there were really toxic,” he says of the days when he focused more on his diet and meditation. ”People who were taking them didn’t seem to be doing that great. And AZT had a different effect on black people. It made their skin turn darker, hair straight, fingernails black. At UHU, we were teaching people holistic ways to deal with HIV, things people called ‘quirky’ years ago. I maintain, with Rainey Cheeks, the reason we lived as long as we did is we were following the UHU program – until one pill a day, which is what I’m on now.”

Recalling the first regimens of 10 to 20 pills a day – plus more pills to manage the side-effects of the first pills – Simmons says that once medication became an effective treatment strategy, the holistic approach was no longer the best approach.

”After you have such a high degree of infection in the sexual networks of black, gay men, you’ve got to lower the viral load,” he says. “You can’t lower viral load with juices. That’s one of the things we’ve been struggling with. I don’t meditate. I’m not as particular about being a vegetarian. I don’t do anything that I used to.”

The good-humored Simmons teases that these days he may be less inclined to craft an exhaustive holistic regimen than to follow a new mantra: ”Eat Twinkies and take the pill.” But while he doesn’t meditate and is less focused on maintaining a vegetarian diet, he reckons much of his lifestyle – avoiding red meat, for example – still adds to his overall health.

Another new turn for UHU goes in the ”good news” pile, more so in that it requires little juggling on Simmons’s part. As National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day approaches, UHU will be marking it as never before. David A. Richardson, a longtime volunteer, has stepped up to offer ”Fire & Desire: A Cocktail of Song & Poetry” on Feb. 6, with music, poetry, a trivia contest and dance. ”I’ve been working on HIV/AIDS prevention since high school,” says the 26-year-old Richardson. ”Typically, my work has involved just volunteering at testing events, retreats, facilitating workshops.”

At 19, he discovered UHU through the organization’s popular weekend retreats. That investment in Richardson is paying off, as he puts the finishing touches on the upcoming event. And while he grants that producing ”Fire & Desire” has been nearly overwhelming, it’s been a labor of love.

”I would love to do it annually,” he says, evidence that however UHU moves ahead, it has held steadfast to building community. ”I didn’t want this to be a sad show. Being able to laugh and celebrate life still happens.”

Richardson doesn’t want his show to scare audiences into getting tested, but to encourage them to get tested for HIV as an act of self-affirmation.

UHU is not only about the HIV-positive, but all things positive. As an organization it is life-affirming and optimistic in the face of huge burdens. Leading UHU forward, Simmons acknowledges some fear in the mix, but he’s not going to let it stop him or his organization.

Looking at the new data he must confront, for example, his so-called ”paradigm shift,” he grants, ”It is scary. Hell, life is scary. … But despite the troubled times, we’ve come a long way. We are still keeping our focus, our commitment to improving the lives of black gay men – those infected and those who are not.”

David A. Richardson presents Fire & Desire, with proceeds benefiting Us Helping Us, on Sunday, Feb. 6, from 7 to 9 p.m., at Busboys & Poets, 2021 14th St. NW. Tickets are $10, or $20 for priority seating, available by calling 202-423-7013 or visiting fireandesireaids.eventbrite.com.

For more information about Us Helping Us, 3636 Georgia Ave. NW, call 202-446-1100, or visit uhupil.org.

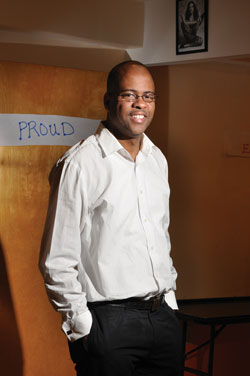

NAME: Ken Pettigrew

TITLE: Director of Programs

YEARS WITH UHU: 10

ROLE: Responsible for supporting the staff and UHU clients in accomplishing tasks, and moderator of weekend retreats.

Ken Pettigrew

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Few know UHU as intimately as Ken Pettigrew does.

”I’ve been a client, a volunteer, a program assistant, a program coordinator, a program manager,” Pettigrew says. “[It’s] worked out because I’ve been able to have different perspectives. I know what it’s like to be in need as a client. But I also know what it’s like to volunteer. I know what it’s like to work for other people and I know what it’s like to manage people.”

Pettigrew, 46, who came to Washington from Chicago in 1989, is currently UHU’s director of programs.

”My job is to look through the lenses of the client, the staff and the organizations or groups who fund us,” he says, adding that he contributes as one of the members of organization’s grant-writing team.

Pettigrew also serves as a facilitator during UHU’s weekend retreats. Last year the organization held 10 support-group type retreats.

”When we go away on the retreats, I take my ‘director of programs’ hat off,” he says. ”People may not even be aware until the end of the experience that I’m the director of programs because I really come in as a facilitator, as a black gay man who shared some of the experiences, same concerns and same hopes. I’m afforded this opportunity to talk to, rather than talk at folks.”

Pettigrew adds that when talking about UHU’s work, it’s important to emphasize that people are having safer sex.

”This notion that HIV is so prevalent in the black gay community because we’re sleeping around, we really want to let folks know that’s not true,” he says. “The majority of the time when we do these retreats guys are telling us that they’re doing the right thing most of the time. But if there’s a slip up and there’s this heavy concentration of HIV in the community, you run [a] risk because of that one slip up.” —Yusef Najafi

NAME: Kenya Hutton

TITLE: Young Adult Coordinator

YEARS WITH UHU: 4

ROLE: Facilitates and coordinates programs for clients between 18 and 24.

Kenya Hutton

(Photo by Todd Franson)

”The youngest person I deal with that is HIV-positive is 16,” Kenya Hutton says of his work as UHU’s young adult coordinator. To reach his audience, Hutton works in programs such as D-Up, which stands for ”Defend Yourself,” and Ebony Distinctions. In the Ebony Distinction program, clients are provided a weekend away in Deep Creek, Md., where discussions are designed to uncover what’s at the cause of certain behaviors.

”We take them away for a weekend to help them connect the dots, why we do the things we do as black gay men, some of the risks that we take,” he says. ”It kind of creates an ‘a-ha!’ moment for many people. They didn’t realize the root of what they were doing, or why they were putting themselves at certain risks.”

D-Up is a community-level intervention. Says Hutton: ”We teach the key stakeholders of the community how to have effective conversations with peers around having safer sex.”

Hutton also facilitates Healthy Relationships for Positive Young Adults, designed to help participants deal with disclosing their HIV status in relationships. And the 32-year-old New York native – who worked prior at the Gay Men’s Health Crisis – maintains UHU’s social-networking initiatives, such as its Facebook page.

Hutton’s four years at UHU have shown him how essential it is to provide youth with a safe space for conversations about HIV and practicing safer sex.

”I think what happens is they don’t have a place where they can go and have these conversations and not feel like they’re being judged,” he says. ”It’s something that a lot of young adults that I deal with are experiencing. When we give them a platform to be able to talk amongst themselves as peers, for a lot of them it’s the first time they’re actually having a serious conversation about HIV prevention. That’s what I noticed here in the D.C. area – there really aren’t many outlets for them.” — Yusef Najafi

NAME: Karen Giles

TITLE: Clinical Social Worker

YEARS WITH UHU: 7

ROLE: Providing psychotherapy to clients and clinical supervision to case managers and peer navigators.

Karen Giles

(Photo by Todd Franson)

How do you provide comfort to people who have just been diagnosed with HIV?

”Primarily through listening,” says Karen Giles, a clinical social worker at UHU. ”Very often, when people come to therapy it’s the first time that someone has really, really listened to them without interjecting their own motives. People feel very hopeless. It’s very difficult for them to visualize a different way of being in the world. So I convey hope.”

Giles does that by walking clients through the stages of loss.

”Any diagnosis of an illness is a loss. People come in, in different stages. Some people are in shock. Some people are in denial. And then someone else may come in where they are no longer in denial but they may be depressed or angry. Especially with people who have been diagnosed for a number of years and have addressed it, they’re already at the acceptance stage.”

Because UHU now accepts third-party reimbursements, Giles is able to also counsel a wide range of people seeking mental health services, including men and women who are HIV-negative.

After earning a master’s degree in social work from the University of Maryland, Giles continued her education with advanced training at the Washington School of Psychiatry. And while she admits that her job is stressful, Giles adds it’s not ”negative stress.”

”There’s a type of stress called ‘eustress.’ It’s like the stress that one would have if they were getting married or if they were having a baby. It’s stressful, but it doesn’t necessarily have a negative impact. So I would describe my work more as eustress than any negative form of stress.”

Giles is motivated by her desire to help African-American gay men live healthy lives.

”I have a son who is an African-American gay male. I think that was the initial interest in UHU. Since then it has evolved. I just have a personal interest in helping people to mitigate suffering.” — Yusef Najafi

NAME: Sharlene Miles

TITLE: Manager of HIV Testing, Counseling and Outreach

YEARS WITH UHU: 8

ROLE: Manage counseling and testing programs, perform HIV tests, counsel clients needing HIV/STD testing.

Sharlene Miles

(Photo by Todd Franson)

People don’t generally walk into a nonprofit organization’s office expecting a little mothering. If, however, they’ve worked with Sharlene Miles, they just might.

”You have to like working with people. I love it,” says Miles, who joined UHU as a volunteer after her corporate job disintegrated in the wake of the Enron-fueled collapses of the turn of the century. ”The second person I tested was 17 years old. He turned out positive. It was hard. That could’ve been my child. That’s why I got really involved with youth.”

She recalls an early client who was so fearful he walked out of his counseling session. Miles followed him outside and kept talking with him, walking up and down the street on ”the hottest day in July.”

”I don’t know how I did it, but I got him back in,” she says. ”Everything was fine, and now he refuses to go to anywhere else to get tested.”

But Miles’s mothering touch isn’t confined to UHU headquarters. She’s out in the field providing testing, in venues ranging from house balls to churches, adapting her message to relate to a teen transgender diva or a reserved senior who may have discovered Cialis. Miles is up for whatever surprises she encounters. After all, the biggest surprise is Miles herself, who insists that if the Ghost of Jobs Future paid her a visit 10 years ago, she would never have believed him.

”I would’ve looked at that ghost and said, ‘That is not me.’ But it has been such a rewarding experience. I’ve met so many people and changed so many lives. And, prayerfully, I know they’ll find a cure for this.” —Will O’Bryan

NAME: Shawn Spencer

TITLE: Medical Case Manager

YEARS WITH UHU: 6

ROLE: Treatment adherence specialist, linking clients to support services.

As the saying goes, a jack of all trades is a master of none. Sometimes, however, circumstances demand that one have both versatility and expertise. Shawn Spencer, UHU’s only staff case manager, lives that existence. Daily he must meet clients where they are, mostly in the figurative sense, but not always.

”One time I put a client in my car and took her to emergency care because she talked about killing herself,” he recalls. That may not have been a typical day, but Spencer doesn’t necessarily have typical days. Instead, he spends his time trying read between the lines of what UHU clients tell him, keeping abreast of all the meds and services that may be available to help them, and not letting it all exhaust him.

”Right now I have an influx of new clients. I start with treatment adherence, help them apply for emergency funding. Some are newly diagnosed. You have to help clients live with the disease. You may have to talk to their partners, families. The first time clients meet you, they might not open up about risk factors.”

It’s a routine that’s anything but routine, with an initial intake appointment lasting up to two hours. As he describes his job, he throws in a statistic that seems unsurprising.

”The average case manager burns out in three years,” he says. ”It’s a juggling act, but I do the best I can. I’ve been lucky to have people to lean on when I get stressed.”

One of those people is Kenya Hutton, program coordinator, who invited Spencer to a UHU-sponsored ”house ball.” Spencer, who is straight, was initially reluctant, but as someone who alleviates stress with photography, it turned out to be a good match.

”It’s a very rewarding job to help people,” he continues. ”But it can be stressful. You have to take care of yourself as best you can.” — Will O’Bryan

NAME: Ernest Walker

TITLE: Manager of Prevention Programs

YEARS WITH UHU: 8

ROLE: Facilitates multiple outreach/prevention programs, supervises support groups and volunteer program, and provides as-needed HIV testing.

Ernest Walker

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Ernest Walker knew about HIV-prevention long before he ever got to UHU – even long before he got to D.C. Born and raised in Seattle, Walker began his career in the Emerald City’s People of Color Against AIDS Network. From there, he landed in Los Angeles and the Minority AIDS Project.

With that institutional background, UHU looked relatively compartmentalized when he arrived, the mental services separate from prevention services, HIV-positive clients separate from HIV-negative clients, and so on.

”Over these past eight years, we’ve bridged the gap between mental health and prevention,” Walker says. ”We’re one organization. Literally, we’re all under one roof. There’s fluidity around people accessing multiple programs, a continuum of care.”

When it comes to continuums, Walker should know what he’s talking about, considering the various UHU retreats and groups in which he has a hand. There are two HIV-prevention retreats and another for HIV-positive, black, gay men to discuss relationships. And nearly any weeknight will find a support group meeting at UHU.

”I’m either working on setting-up a retreat, wrapping up a retreat, getting ready to do ‘Popular Opinion Leader,” he says, ticking through his days. ”If you look at my planner, there are so many different things happening.”

Along with the variety and full days come immeasurable rewards.

”I go through times where I’ll say, ‘I love what I’m doing.’ Then I’ll get to where I’m feeling overwhelmed. Then one or two clients might call you to thank you for a conversation or an intervention, and show me this is where I should be. It gives you that that feeling, ‘I guess I am doing what I’m supposed to be doing.”’ — Will O’Bryan

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!