The Great Septime

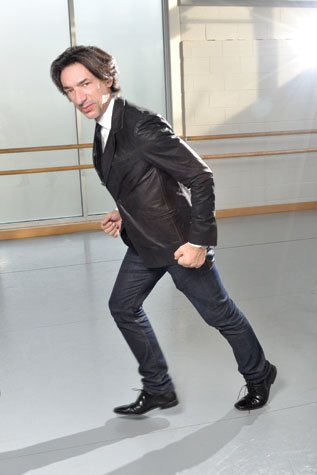

The Washington Ballet's Septime Webre is one of the dance world's most celebrated talents

Septime Webre was drawn to dance early.

”I’m half-Cuban,” he says, “and there’s an old Cuban saying that Cubans dance before they can walk.”

Septime Webre

(Photo by Todd Franson)

The seventh of eight children — his first name Septime stems from the Latin word for ”seventh” — Webre remembers living in the Bahamas as a toddler, when his six older brothers would ”push back the sofa and put on old Cuban salsa albums and we’d just dance and have a dance party.”

”From my background of Cuba, the Bahamas, south Texas,” he says, ”I couldn’t envision I could have a place in the world of classical ballet.”

So after graduating high school, Webre pursued a history/pre-law degree at the University of Texas at Austin. He even worked a year as a personal assistant to the late Ann Richards, when she was state treasurer.

”She was so funny,” Webre says, about the woman he describes as ”the beehive-bedecked former governor of Texas.” ”She used to say all the time,” he imitates her famous Texas drawl: ”Septime, my waist is as big as one of your thighs.”

His slim figure was in part a result of the ballet training he was putting in whatever spare time he had. After years of dance dabbling, Webre finally decided to make ballet his career, joining Ballet Austin and then setting out for New York in the 1980s.

Once in New York, Webre began to shed the ”outsider” status he’d always felt, most importantly for being a creative gay boy. ”I knew I had something special about me, I didn’t quite know what it was,” he says. ”But I knew it was not valued in Brownsville, Texas, when I was being emotionally bullied in high school, picked on for being gay.”

Webre quickly came into his own in the dance world, first in New York, and then in D.C., where for the last 12 years he’s served as artistic director for The Washington Ballet. Webre has become one of the dance world’s most celebrated leaders, and he’s turned The Washington Ballet into a dance juggernaut, one of the nation’s leading ballet companies. Under his leadership, the company’s budget has tripled, from $2.8 million in 1999 to $8.5 million today. He’s also developed a strong educational outreach program with D.C. public schools, and helped grow the company’s Washington School of Ballet from 350 to 900 students in just the past six years. In 2000, the ballet became the first American company in 60 years to perform in Cuba. And Webre is itching to tour Cuba with the company again.

The company still operates out of the home of its founder and Webre’s only predecessor, the late Mary Day. Webre has converted her large house, situated in a tony Northwest neighborhood north of the Washington Cathedral, into office space as well as several dance studios. His office is, fittingly, in Day’s old master suite. In one corner of his office sits a nutcracker, a gift from a former student dancer in the 50-year-old Washington Ballet’s annual Nutcracker program.

Over the past decade, Webre, who’s about to turn 50 himself, has also become an increasingly prolific choreographer.

Of all his works, Webre is most proud of The Great Gatsby, his take on the classic F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. The company will stage a revival of the ballet next week at the Kennedy Center.

”I think [The Great Gatsby] is a real synthesis [of my ideas], a great fusion of music and dance — raucous, athletic dancing — [with] hopefully crisp and emotional storytelling.”

Webre aims to keep growing as a choreographer, and hopes to keep pushing the Washington Ballet to tackle new frontiers — specifically television.

”I got called today to ask about a reality TV show here,” Webre says. ”A production company would like to do a Washington Ballet [reality series].”

Increasingly, Septime Webre is ready for his close-up.

METRO WEEKLY: I understand you’re from a large family. Where did you grow up?

SEPTIME WEBRE: I’m the seventh son in a family of eight brothers and one sister. The six older brothers were all born in Cuba, and my family left during the revolution. I was born in the states but grew up in the Bahamas until I was 12, and then south Texas throughout junior high and high school, although during those years we were spending a lot of time in Africa. I spent summers and Christmases in the Côte d’Ivoire and Sudan from the time I was about 14 through college. My dad designed sugar mills and sugar factories, and he was doing that in various places where there were sugar industries.

MW: Did your parents encourage you to pursue a career in the arts?

WEBRE: No, I came from a family that stressed the professions, so we were expected to become engineers or lawyers or architects. I told my parents I was going to be a Jesuit priest. I was the seventh one, the sensitive one. [Laughs.] And so I was going to be a Jesuit.

But in fact I was star-struck young. When I was about 10 I became the family playwright. My first play was called The Case of the Recurring Ennui. I knew the word ”ennui” meant something like bored. And my sister, who was 8, was my muse. When the play started she was wearing a white, fishtail gown I made out of the canopy from her bed with safety pins. And she was lying on a chaise I made out of suitcases and a red, crushed-velvet bedspread. You know we Cuban Americans always have some red velvet in the closet, just in case. And her first line was, ”Oh, I’ve never been so ennui in all my life!”

MW: That’s a great line. You performed this for the whole family?

WEBRE: For the neighborhood, actually. My parents were very social, so they’d have dinner parties. We’d put together surprise plays after the dinner party, to which we were not invited. We’d pop in and say after the dessert was served, ”Okay everybody, upstairs to the game room to see the play.” Usually it was a musical, usually there were multiple costume changes. And I had written it, directed it and choreographed it, [and it starred] my siblings and some neighborhood friends.

MW: But because you didn’t have their support in the arts, you decided to pursue a career as a Jesuit priest?

WEBRE: Well, until I was age 15. Then I told everyone I was going to be a lawyer. I was somewhat interested in politics. It was the same year I was attacked by a baboon in the Côte d’Ivoire. Those are unrelated facts, [just] sort of funny.

MW: Wait, you were attacked by a baboon?

WEBRE: Yes. We were visiting the brush, in the savannah of the Côte d’Ivoire, out in the country, in a little village with mud huts with thatched roofs. And there was a fence, and a baboon leaped out and attacked me. But because there was the fence, his whole body couldn’t get through, so it was only about a minute-long struggle.

MW: Were you injured? What did your family do?

WEBRE: There was a lot of blood, but no [physical] scars. But because my mother and all of my siblings ran, screaming in terror, and no one stayed to help me, I was somewhat traumatized by that fact. It’s still joked about in the family, ”Hey, remember that time Mom ran when you were attacked by the baboon.” [Laughs.]

MW: I imagine you might have nightmares about baboons because of it.

WEBRE: No, I don’t. I do collect taxidermy, and I’m going to get a baboon one of these days.

MW: Did your being gay factor into the decision against becoming a priest?

WEBRE: It didn’t at that moment. I didn’t really self-identify as gay at the time. It was really about the logic.

The specificity of dogma in the Catholic Church just seemed too irrational to a logical 15-year-old’s mind. It just didn’t seem to be right to me. I remember thinking, ”The purported facts surrounding Calvary seemed too much like magic. That certainly couldn’t happen. That’s not true.” It was on that level.

Later, particularly when I moved to New York in 1987, Cardinal O’Connor and the Catholic Church were not behaving very well in the face of the AIDS crisis. And that was something that was important to me and was in my life. That was the time of protests at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. There was a period when I was actively avoiding the Catholic Church. I think the Catholic Church has gone beyond that, and I’ve gone beyond my issues there. So I know there’s good and bad in lots of institutions.

I have retained a kind of ethnic identity as a Catholic for sure. And feel very comfortable in a Catholic liturgy, which I attend occasionally. And still consider myself a spiritual person. But not a practicing Catholic.

MW: How does being gay inform your work in dance and with the company?

WEBRE: I haven’t been asked that question before, oddly.

I grew up as an outsider. Certainly, growing up gay gave me that status. Also, we were Cuban refugees. My parents left Cuba with $5 hidden in my brother’s shoe a year before I was born. We lived as Cuban refugees and therefore outsiders. I was a kind of ”fake” Latino also: My older brothers’ first language was Spanish, [but] we spoke English at home. We were not encouraged to present ourselves as Latinos in school. I spent a lot of time as a teenager in Africa, with just my brothers and sister to hang out, sort of tribal. When we moved back to south Texas it was a cultural shock. It’s all football and cheerleading.

I think being gay enabled me to be free enough to reject the path not just that had been selected for me, but that I had even thought I would follow, which was first to be a Jesuit, and then to be an attorney. I had to let go of ideas, to accept that I was gay. That freed me to let go of other ideas about what might be my life’s work. So it fueled me on this journey.

Good training and the hard work in the studio made me a dancer. The outsider, the global and gay experiences, made me the choreographer and director.

The other part of the question might be, ”Is there a gay sensibility to my work?” I think the work is an accumulation of many factors. They include who I am in total: an ex-Catholic who knows a heck of a lot about baroque church and design; being gay; being interested in 20th century American classic literature; being interested in contemporary visual arts; being interested in different kinds of music. All those things collectively find their way into the work.

And also the dancers I’m working with find themselves in the work, because I make the work for particular artists always. It’s never devoid, it’s never anything abstract. I created the role of Jay Gatsby for [The Washinton Ballet’s] Jared Nelson. I had him in mind. Sona Kharatian’s Myrtle Wilson is amazing. It would be a different kind of Myrtle with a different dancer.

MW: What inspired you to take on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel?

WEBRE: My first exposure to The Great Gatsby was when I was in seventh grade, and the Robert Redford and the Mia Farrow movie came out. I was obsessed with it. I watched it three or four times. And I had a big crush on [the protagonist] Nick Carraway. It led me to read the book in my teen years, and I just thought the book — Fitzgerald’s language is so poetic and spot-on. I relate to Carraway’s philosophical approach to the world.

I have always thought that it would make a great ballet. There are just so many juicy roles, and the period speaks of dance. There’s a kind of buoyant, energetic optimism of the 1920s. And it’s a story that has muscles. If we think of iconic images of the ’20s, it’s flappers with angular attitudes — these are images of people dancing. And the music of the era is about dance, and about wild, exhilarating dance. I’ve been thinking about it since my 20s actually.

I started to think about it again as the current economic difficulties began [four years ago]. If there is a story of the price of excess and capitalism unfettered intrinsic in Gatsby, it’s also present today. So I think there’s an interesting parallel in the message to today’s world.

MW: And in addition to your company, you’ve enlisted two of Washington’s finest actors, Will Gartshore and E. Faye Butler, to help tell the tale.

WEBRE: Will Gartshore plays a matinee idol crooner. The role of Nick Carraway is performed by both a narrator, an actor and a dancer. [Gartshore] plays Nick Carraway as an actor. I wanted F. Scott Fitzgerald’s language to be present, so he has about five short monologues to help set the scene and tell the story. And E. Faye Butler just blows the roof off any gin joint. Her ”I Want A Little Sugar in My Bowl” is really one of the most astonishing performances I’ve seen in years. [It] leaves everyone slack-jawed.

MW: Anyone who’s seen her perform has no doubt about that. And tap dancer ‘Quynn Johnson also performs?

WEBRE: Yes, she’s great. The tap-dancer is a metaphor for the thunder — the sound of the tap-dancer is thunder. And also kind of abstract expression of the emotional turmoil that’s going on inside of the characters, maybe two-thirds of the way through the ballet as we start to begin the build to the final climax.

MW: Is the current production pretty much as it was two years ago when it premiered?

WEBRE: No, two years ago was the first iteration, like the first draft of a novel perhaps. I haven’t changed the structure, but everything is much more refined and clear. What I was seeking was to embody the chaos of the period, but also to have the clarity of Fitzgerald’s language. I made some adjustments. We have a few new performers, new dancers going into roles, which is always exciting.

MW: You were basically a late bloomer as a professional dancer yourself, since you didn’t start until after college.

WEBRE: Yeah, my first professional job wasn’t until I was 22. Which is quite unusual. Usually dancers enter the profession at age 18.

MW: You don’t dance anymore?

WEBRE: No, no, I’m way over the hill. [Laughs.]

MW: When did you stop?

WEBRE: When I was 30. Although last year I actually came back. I got back in shape and revived an old piece of mine called, Shoogie: The Tale of My Weiner Dog. It was kind of a novelty.

MW: That was an autobiographical piece?

WEBRE: Somewhat. [It was] about growing up in Texas. It was sort of a fantasia about my weiner dog Shoogie, who starts taking on water and eventually explodes around the neighborhood. That part didn’t really happen. [Laughs.] There was a Shoogie, and she did start taking on water and swelled up like a watermelon. But she belonged to my friend. It’s one of those fictional stories that were patched together from real-life.

MW: How was it returning to dancing?

WEBRE: Hard as hell. But I made it through and it was fun. There’s really [only] a short dance solo and a 20-minute monologue. And the monologue was much more nerve-wracking than the dancing, just to memorize all that and do it the same every night. I don’t know how actors do it. [Laughs.]

MW: When did you start choreographing?

WEBRE: My first ballet, apart from the dances I would fashion when I was a kid, was called D-Construction. It was to the music of John Cage. I was probably 24 years old. It was very athletic and abstract but driving. It was just a couple years before I danced for Merce [Cunningham], and I chose the music because I was interested in new, and I was a huge fan of Merce’s work. And through seeing Merce’s choreography and Merce’s company, I got to know John’s music.

MW: Did you work with John Cage on that?

WEBRE: I didn’t work with him on the piece, and he actually never saw it. I was a little too embarrassed to show it to him because Merce, the great master, had made so many works to John Cage’s music, I didn’t want to be compared. I was a kid apprentice. But that work has survived actually. It’s my first work and it’s still performed. It just went up last year at Goucher College and it’s still in repertory at various companies.

MW: Meanwhile, your company has been performing your version of The Nutcracker, set in Washington, for what, eight years now?

WEBRE: Since 2004. More importantly, this [year] is the 50th anniversary of the world premiere of Mary Day’s Nutcracker for The Washington Ballet.

MW: I understand you’ll be able to celebrate it in traditional fashion, with live musical accompaniment.

WEBRE: Two years ago, faced with a massive, million-dollar-a-year cut from the city government, we had to cancel our Nutcracker orchestra [and use pre-recorded music instead]. Two weeks ago we announced that Adrienne Arsht made a gift of $250,000 for us to restore live music to The Nutcracker this year. The gift was just for this year. Certainly we want to make live music a priority, but we’re funding one season at a time at this point.

The Nutcracker has been really successful for us. I’m really proud of the work. It’s unexpected, fresh, it’s a big show, filled with a lot of surprises. I think the use of kids has been heartwarming, but also we use them in a very professional fashion in the production.

MW: How is the company doing?

WEBRE: Artistically, we’re doing really well. There are three parts to our organization: our company, our school and our community programs. The company’s doing great, just dancing beautifully, success after success. Really the last year the company has risen to I think its highest level ever. The school has grown amazingly. And our community engagement programs are doing beautifully. We have two programs: DanceDC, all around the District and the D.C. public school system, and a big program at THEARC in Anacostia.

Ticket sales have held up really well. We are still struggling to make up for the fact that we had been receiving a million dollars a year from the city. For two years now, that’s gone from a million to zero. We still receive money from the arts commission, but this was a line item from the city’s annual budget to support the company. So we’re struggling to make up for that loss. It’s still a struggle, but we’re solvent.

MW: What do you see for the future, for you and the company?

WEBRE: Well, I hope the next 50 years. I want the company to continue to grow and be vibrant and contribute to the language of the art form by being a creative company not afraid to tackle new things. While we do big classical ballets like Don Quixote and Le Corsaire, I think what we do special is new work made for our dancers. That’s what separates us, puts us apart [from other companies]. In that way we contrast wonderfully with the other ballet programming that the Kennedy Center brings in: The largest ballet companies in the world doing very large, full-length ballets. [So] creativity and invention can be our hallmarks.

MW: How do you see the state of dance in general faring?

WEBRE: I think we’re in the same boat as every other art form and just about every other industry. The current economic climate has made it difficult from a government funding perspective, and to some degree foundations, because they rely on the stock market. But individual giving and ticket sales have remained really strong and we’re excited about that.

Artistically speaking, I think dance is progressing forward. What’s run of the mill now compared to what was run of the mill even when I was dancing 20 years ago in top form is like night and day. The technique is progressing forward. In some ways, the dancer’s technique is progressing a little faster than the choreographic ideas right now. Because it’s moving so quickly, the training. What male and female dancers can do is so high now, it’s incumbent upon choreographers to stretch the dancers.

MW: Tell me more about the call you got from the TV producers wanting to feature The Washington Ballet. Do you think you’ll do it?

WEBRE: We’ll see. It’s not a Toddlers & Tiaras situation, or a Real Housewives of the Ballet World. [Laughs.]

MW: You don’t want to do those kinds of shows?

WEBRE: No, no. There’s nothing to gain from that. But the real-life stories [and a serious-minded approach] makes audience members more connected. So I’m not against that.

MW: What has been the impact on dance, if any, of shows like So You Think You Can Dance? Or even the film Black Swan?

WEBRE: Anything that helps put the spotlight on dance is helpful, honestly. So I think it’s great. So You Think You Can Dance has given an outlet to a certain kind of contemporary dance that is commercial, but actually a lot of it is quite good and inventive. So I think it’s good for the industry. Just as I thought with Black Swan. I mean, Black Swan made dancers seem neurotic, and it made artistic directors look like bastards. But it was good to have the spotlight for a little bit. It exposed a lot of Americans and audience members to Swan Lake, and they’re more likely to buy tickets to the real Swan Lake now, since they’ve seen Black Swan.

MW: So you’re saying you’re not a bastard?

WEBRE: I don’t think so. My mom wouldn’t have said that. [Laughs.]

MW: Do you like So You Think You Can Dance?

WEBRE: I don’t really watch television, except I’m hooked on Family Guy and Big Love, although it’s over now. And a secret pleasure: I do watch True Blood. But that’s about it. So I don’t really watch So You Think You Can Dance. But if people watch So You Think You Can Dance, they now have become dance-goers, technically. So they see themselves as dance watchers. And I hope that will translate into interest in coming to see dance in a theater.

MW: You’ve been in D.C. since 1999. How do you find living here?

WEBRE: I love D.C. I find it increasingly cultured and cosmopolitan. And it’s so green, and easy. I love the urban feel of Adams Morgan, where I live. My daily home life in Adams Morgan and Logan Circle and Dupont, it feels urban. I miss the edge of New York, but D.C. just feels so like home.

MW: Did your parents come around to your ”flighty artist” life?

WEBRE: My parents are no longer living, sadly. But when I became [an artistic] director at age 30, my mother was so funny. I was director of the American Repertory Ballet in Princeton [N.J.], and I also was teaching at Princeton [University]. And every Sunday night she’d call me and we’d have a Sunday night chat, and she’d say, ”Oy pero Septime, yes I saw the article about you in The New York Times. Congratulations. Yes, but you know, you could still go to law school at night at Princeton. I know they would take you.”’

She really still had this idea, of course. And then when she started to see my work — the work in my 20s was quite aggressive, physical — and she’d say, ”Oh yes, darling, I liked that, but the music. Don’t you like Tchaikovsky? I want you to make a pretty ballet.” And so actually it happens that the first ballet I made after my mother passed away was Romeo + Juliet, which I dedicated to her, because she always wanted me to make a pretty ballet.

The Washington Ballet’s The Great Gatsby runs ‘Wednesday, Nov. 2, through Sunday, Nov. 6, at the ‘Kennedy Center. Tickets are $20 to $125. Call 202-467-4600 or visit kennedy-center.org. For more information on The Washington Ballet, visit washingtonballet.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!