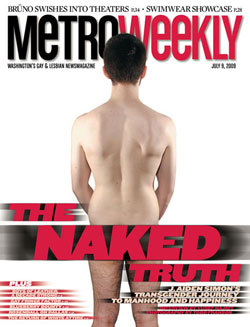

The Naked Truth

J. Aiden Simon's transgender journey to manhood and happiness

There are 10 naked men hanging at The DC Center.

They are all covering their genitals, part of “Member,” a photo exhibit by Baltimore photographer J. Aiden Simon. Slated to run through the end of July, “Member” explores the different degrees of masculinity among gay, bi, straight and transgender men.

J. Aiden Simon

Simon is one of the 10 standing in the buff. Meeting him, it’s impossible to tell that this 20-year-old man was born with the body of a female. That’s because the 5-foot, 4-inch, native of Stamford, Conn., is just one of the guys. He’s certainly masculine. As one attendant during the June 26 opening night of the exhibit pointed out with a friendly laugh, “You are very hairy.”

That’s the point Simon hopes to make: You can’t always tell who is transgender… or gay… or bi…. or straight. And penis size has very little to do with masculinity.

Currently a senior at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Simon has explored similar topics while documenting his own transition to manhood on his Web site with self-portraits, art and even a children’s book called But I’m a Boy. He’s an active member of the GLBT community, helping to lead the Maryland Institute Queer Alliance. And this summer he returns to Stamford for an internship with renowned photographer Renee Cox.

As he readied to leave, Simon talked with Metro Weekly about his own body of work and how it has helped him evolve to see himself fully. “At one point,” he says, “photography was a way for me to see how my body was changing and really see what it looked like.”

METRO WEEKLY: Is “Member” your first exhibit?

J. AIDEN SIMON: It’s the first time I’ve had a solo show off-campus. I had a photograph in an exhibition when I was in high school, but [that exhibition] was a lot smaller.

MW: What was that photograph?

SIMON: There’s this smiling Ken doll and he has his arms up, and then there are two Barbies you see from behind. One has a toy knife, and the other has a gun. And so it was just about reversing the gender roles a little bit and the fact that Ken was happy about it.

MW: How did “Member” end up at The DC Center?

SIMON: I put my Web site online in January of this year and posted that project in a few places and just let it seep out into the Internet. The D.C. Trans Coalition contacted me. They were working on a conference called “Just One of the Guys,” which was a conversation between bi- or gay- identified men and trans men, talking about issues around disclosure and bathroom issues and doctors and all these things, and how we can start to talk together to have more knowledge out there.

They wanted to include a visual element to that and so they called me and said, “Please, please, please, please, show your work at our conference. We really want it. This would be perfect.”

And I said, “Of course I’ll show it. Why are you begging me?” Then they said they wanted to leave it up longer so that if people didn’t have a chance to see it at the conference, they’d have another chance to see it [at The DC Center].

MW: What do you want people to get out of “Member”?

SIMON: That being a man doesn’t mean you have to have a penis, or a penis of a certain size. There are a lot of [existing] photographs of trans people and they are all saying the same thing: Trans people are human. I feel like we should be so much further than we are with art and photography of trans people. I want people to be able to have a space to start a dialogue about being a man, having a body, identifying your body as being a man’s body, and the whole issue of equating having a penis with being a man and how pervasive that is in our culture — and how damaging it is for everybody.

Another thing I want people to realize is that you can’t always tell that somebody is trans. Even as a trans person it’s hard to tell if somebody is trans, if not impossible often. That’s kind of the point.

MW: Is that why you use an anonymous chart with the photos that does not reveal which models are gay, straight or transgender?

SIMON: Right. One aspect of that in all reality is that a lot of trans people don’t want to have an image of them connected to something that says they’re trans because it will exist forever and ever. But really my purpose in doing that is that I want people to look beyond it. It’s not supposed to be, “Figure out who’s trans and who’s not, and who’s gay and who’s not.” The point of the chart, especially, is to be able to look at the variations among all of the men and see how diverse the population of men is.

MW: Was it difficult to get people to pose naked for the exhibit?

SIMON: They knew when they agreed to be photographed that they would be naked. Some people were less comfortable than others, but it was a very fast shoot. It was very quick and I did that so I could get their initial reaction, their raw emotion, being in front of me.

MW: Why did you call the show “Member?”

SIMON: It just kind of clicked because I had been looking for a word to bridge the idea that there are members of a group as men, but there’s also member being a euphemism for the penis.

MW: Let’s talk about the art on your Web site. I noticed a 2007 self-portrait titled “Baby Carrot vs. Banana” in which you are nude and holding a baby carrot in place of where your penis would be. In another photo, you are holding a banana. What were you going for with that piece?

SIMON: That one came before my “Member” series, when I was thinking about the same things, about penis size and all that sort of stuff. I had stopped taking self-portraits basically when I started testosterone. Or maybe a little bit before then, and it really took a lot of time to re-adjust my body and get comfortable photographing myself with the intention that other people would see it. I realized that self-portraiture was really strong for me and really important to me, and so that was the first time in a few years that I had taken self-portraits. Mostly it’s just about penis size.

MW: There’s a very feminine self-portrait series on your Web site, where you have long hair. Is that before you started transitioning and taking testosterone?

SIMON: Yes. I shot all those when I was in high school between 2004 and 2006, and for a while I was uncomfortable showing people that work. After I had begun transitioning and dealing with all the gender stuff, I just kind of decided that I felt it was strong work.

MW: How does it make you feel to look at it now that you have transitioned?

SIMON: I see a lot of pain. [I see] all of the things that I was dealing with, with my body, which came out in those photographs — how to fit my body into different spaces, how to make my body look more feminine or more masculine, depending on what I was going for. I see a lot of emptiness in them.

MW: Do you see yourself or somebody else?

SIMON: Kind of both. I remember being there and I remember shooting the photographs. But I don’t really feel connected with the body that I see in those photographs.

MW: Let’s talk about your history. I should first ask you, how do you identify?

SIMON: As more or less a straight man, and a Jew, and an artist, and a lot of other things besides that.

MW: You were born a girl. What are your earliest memories of feeling different from other girls?

SIMON: That’s hard to say. I don’t really know. I was 16 when I knew I needed to transition, but that was after dealing with a lot of other things. I needed to either transition or keep living as an empty person [and] continue to try to kill myself. Those were the options. It wasn’t really like, “Am I going to live as a guy or live as a girl?” It was, “Am I going to live as a guy who is pretending to be a girl and not really living as anything?” or, “live as a guy and deal with how people feel about it?”

But as far as my childhood, I wasn’t overly masculine. I played soccer as a kid. I remember very clearly hating dresses. I remember hating having long hair. I didn’t necessarily know that I was different per se. All of my friends, even mostly now, are girls. That hasn’t changed.

MW: Would you say you identified more as a tomboy and didn’t feel like there was a deeper issue at hand?

SIMON: I knew that things were wrong, but there were so many things going on that it was hard to narrow it down to gender, as opposed to all these family things that were happening. My mother is very, very, very feminine, so we had a hard time when I was growing up with clothing and hair issues and things like that.

MW: Because she wanted to celebrate those things, and you didn’t?

SIMON: Yeah, very much so. Like she wanted to blow dry my bangs and I wanted nothing to do with having bangs, or having long hair, or a blow dryer, or a dress.

When I told my parents I was going to transition, from my point of view, she had a harder time than my dad did. Partly because she identifies with her body and I was rejecting the type of body that she has. But now that I’m happy and functioning well and my parents can see that, we have a much closer relationship.

MW: When did you start to realize you are male?

SIMON: I was 12, reading a magazine article about a [female-to-male] trans guy, and I remember tearing out the article and saving it. I remember thinking I wanted to look like him but didn’t really stop to say, “Why do I want to look like him? Why am I interested in this?”

At summer camp, when I was 14 or 15, there was somebody who wore very masculine clothes, always playing sports with the guys, who had more guy friends than girlfriends, and was getting tormented by the girls. We talked one night and this person said to me, “I feel like a guy and when I get older I’m going to transition. Do you feel that way, too?” And I was like, “No.”

Experiences like that, where I was seeing other kids getting treated badly for their gender behavior, really made me not want to be like that. Which is interesting, too, in retrospect, because nobody treated me badly for having a girlfriend.

I was presenting myself a little bit more masculinely than I had been when I was younger. I was even confused about why the person [at camp] even confronted me about those issues. I think that I just didn’t even want to go there — at all. Once I was done dealing with all the family stuff and started seeing therapists, getting through a lot of other things that were going on, I told a friend that I was trans.

MW: Before you started transitioning, when you were dating a girl, did you identify as a lesbian?

SIMON: That’s what I would call myself. There was no other word for it.

MW: Was there any particular reason for coming out to that friend?

SIMON: I knew I was leaving for college somewhat soon. It was somebody who I trusted a lot, who I had actually encouraged to come out as gay. She was also a friend that isn’t connected to any of my other friends. She’s a friend that I made somewhere else, that didn’t go to school with me, and didn’t live in my town. I told her one day and she was basically like, “Well, that makes sense.” Partly because at the time that I met her, I had cut my hair short and I was wearing guy’s clothes. The next person I told was my ex-girlfriend, the first girl that I dated. I decided to write her a letter and she gave me a call and said, “I love you, no matter what.”

I felt like I had somebody who I cared about, who cared about me, in my safety, who said it was okay. That was what I needed to be able to tell my parents, because my feeling was that my parents were going to disown me. It would at least be really rough for a long time.

Soon thereafter I had written my parents a letter. About a month before I went to college, I gave it to them. They came to a therapy session with me. My mom was very much, “Maybe you feel this way because you’re uncomfortable with your body, but there are other things that would make you feel better like a boob job or something like that.”

Which was obviously quite the opposite of what I was planning. I was at a point in my life where I didn’t give my parents a lot of time to process, partly because I didn’t want to talk about it. I just wanted them to feel okay, or not okay, and move forward from there. Freshman year was a tough time for my family.

MW: What was the month between giving them the letter and leaving for college like?

SIMON: My dad was starting to come around, but my mom was still having a very hard time. She was still calling me by female pronouns and by the name they gave me when I was born. And she didn’t want me to tell anyone what I was feeling. Other family members would come over and she would say, “Don’t talk about it, don’t bring it up. It’s going to be really hard for them and they’re not going to be able to handle it.”

There was a lot of fighting. My dad was trying to be the peacemaker. It took a really long time, but I think some of the things that have helped are obviously seeing me happier, and seeing me functioning and not being self-destructive, and not needing medication, and also seeing that other family members are accepting.

Part of this was that we had lost basically my mom’s side of the family through this really messy family dispute. Her family was the type that would cast people out for anything. [For example,] she married my dad and converted to Judaism from Catholicism and came very close to being disowned by her family. Her mom almost didn’t come to my parents’ wedding. My mom comes from a place of considering first what others will say, and second considering how she feels. She is now beginning to re-think those things.

My sister initially was fine, but didn’t want to talk about it. When I started hormones she didn’t really want to hang out with me.

After freshman year I got chest surgery, which was the best thing I could have done for myself, to get it over with. Now I don’t even need to think about it at all.

MW: Were you afraid to complete the chest surgery?

SIMON: Not really. I knew that I would be in pain after the surgery, but I knew that it would only be a few weeks and that afterward I wouldn’t have to deal with what I had been dealing with every day.

MW: Did your parents tell you not to do it?

SIMON: Yeah. I think they wanted me to wait until I was older. Which was kind of their opinion on the whole thing: Either wait until you are out of college, or wait until you are married and have kids. It was not really a good idea.

MW: What happened when you woke up from the surgery?

SIMON: I tried to look at my chest, but I had bandages on.

(Photo by J. Aiden Simon)

MW: And when you finally saw yourself?

SIMON: It was wonderful. I guess the first time I saw my chest was that next day. I don’t really remember exactly, but it felt great. It’s almost hard to remember because my chest has been this way for two years now and at this point I kind of take it for granted.

MW: Because mentally you were always who you are?

SIMON: Yeah. And it’s just kind of like I’ve put all of that — having to bind, having to feel uncomfortable about my body, not wanting people to touch me, being nervous about people looking at me — behind me. I don’t think about it all that much. It made a lot of everyday things a lot easier. That’s what it really comes down to: not having that stress every morning when I wake up.

MW: What about the lower portion of your body? Did you consider making a full transition at the same time you decided to have your chest surgery?

SIMON: I think that at that point I very much didn’t want to have bottom surgery. But as time has gone on, that right now is very much a question for me.

I’m not sure if my discomfort with my genitalia is because of societal expectations or if I really, truly, honestly will always be uncomfortable. Which is not to say that I am extremely uncomfortable. I can have penetrative sex without anything and that’s fine. I’m fine using what I’ve got. But at the same time, it would be nice to have everything look the way it’s supposed to.

But I’m not going to decide until I can figure out what the reason is that I want bottom surgery.

MW: Do you still have to take testosterone?

SIMON: Yes.

MW: What else do you have to take?

SIMON: That’s it.

MW: Did your voice drop after you started taking testosterone?

SIMON: Yeah. Somehow in communicating my prescription to the pharmacy — between my doctor, the pharmacy, and the nurse who first showed me how to inject — my testosterone dose was doubled for the first three months. [Laughs.]

It kicked my body in the ass, and my voice literally started dropping within three days. It was audible to the point where one of my friends was like, “Stop over-compensating.” And I was like, “I’m not. There’s nothing I can do about it — this is really happening.” Which was wonderful. I was just so happy and so much more comfortable. People started telling me that I had started smiling.

MW: Why did you name yourself Joseph Aiden?

SIMON: I felt that I should take a familial name [and] two of my four great grandparents were named Joseph. And my father’s initials are J.S., and I wanted to keep his initials. That was always something that I felt I should have had.

MW: Where does Aiden come from?

SIMON: It really was just a name that stuck when I was looking through names.

MW: Do you mind if I ask what your parents named you?

SIMON: Yes. I know trans people whose old names I know. I feel like it changes your perception of them, not consciously, but maybe you can get more of an idea of what they used to be like.

MW: What is your reaction to what’s happening nationally with Chaz Bono?

SIMON: As much as I don’t really like celebrity culture, I think that it’s good to have a famous family that’s accepting their child — enough to feel comfortable going to the media.

MW: Has it generated more dialogue for you, between any of your friends or family members?

SIMON: Not Chaz Bono, no. We’ve definitely talked about Thomas Beatty, but I think everyone has talked about that.

I’m starting to come up with ideas for my thesis project. I don’t know yet if it’s going to be a funny project or a serious project, but I’m thinking about possibly dealing with pregnant men. Thomas Beatty was received really badly, not completely because there were so many other things wrong with that whole situation, but primarily because of the photograph that was published of him. It was a very, very effeminate photograph, the way that he was standing, and it was softened and everything.

I’m thinking if I can make a pregnant belly that I’m going to be looking at masculine stereotypes and doing very stereotypically masculine things as a pregnant man. But I’m ambivalent about that because there are so many other parts of pregnancy, emotional things, that I have no idea about and I will never have any idea about. So I’m not sure if I have the right as an artist to be talking about that.

MW: Do you think you’ll ever do work that’s not transgender-related?

SIMON: There may come a time, but in the near future, no. But I’m also sometimes working with memory and the way that photography affects our memory and our ability to recall things — how we rewrite our memory based on snapshots of things that we’ve seen, or things that have been told to us. I did one project where I scanned family snapshots and changed myself so that I was wearing boy colors and had shorter hair. It was like talking about the issue of bending the truth or lying about your childhood if you are a trans person. Sometimes if you don’t want to out yourself as a trans person, you will change things when you are telling a story.

MW: Does it bother you to look at those childhood photographs?

SIMON: Depends on the photograph. There are a lot of photographs where I see more or less what I remember myself to be like, or at least at certain ages where I had control over my self presentation, where I was presenting myself a little more masculinely as a kid. Those don’t bother me so much.

But there are a few pictures, for whatever reason, that I see myself looking very feminine that I don’t really like. Sometimes I am looking at them to see what was going on when I was a kid, trying to analyze my childhood. What did I really look like? Was there anything that should have been visible?

I have this theory that anytime you access your memories, you kind of rewrite them because you imagine yourself yesterday as yourself today. And so that whole process of editing memories is very interesting to me.

MW: What advice would you give to someone who is going through what you were going through before you put the pieces of the puzzle together?

SIMON: I’d say find something you’re passionate about — an outlet for your emotions is healthy for anyone — as well as good friends and a therapist who is not transphobic.

MW: How have your parents reacted to your nude self-portraits and other pieces?

SIMON: I feel uncomfortable showing people my work sometimes. I have explained my “Member” series to both of my parents, and my mom doesn’t really seem to understand. But they’re supportive of me being an artist — not so much of me being an artist who probably won’t be able to make a salary. My [parents] both grew up around art and have an appreciation for it and know that I love what I’m doing.

MW: It sounds like you’ve arrived.

SIMON: It’s hard to gauge, in retrospect, how unhappy I was. I remember being unhappy, but I don’t remember the feeling so much.

That’s something that has changed maybe partly because I’m in art school and happier with what I’m doing, but also because I’ve transitioned and have become more comfortable interacting with people.

J. Aiden Simon’s “Member” series is on display at the DC Center, 1111 14th St. NW, Suite 350, and open to the public Monday through Friday from 2:30 to 6:30 p.m., through the end of July. For more information, visit www.jaidensimon.com or www.thedccenter.org, or call 202-682-2245.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!