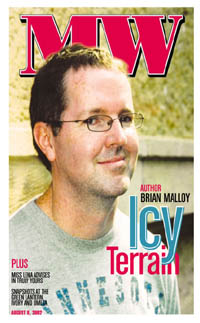

Icy Terrain

Novelist Brian Malloy

Photography by Michael Wichita

|

Write what you know.

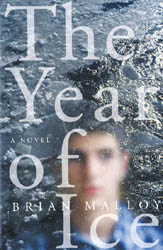

It’s the sage advice all aspiring novelists hear, and Brian Malloy took it to heart when creating his debut work, The Year of Ice. It’s how Malloy created his young protagonist Kevin Doyle, an aimless, underachieving high school senior in 1978 Minneapolis who lives for rock concerts, keg parties, and unrequited desire for a handsome, all-too-straight classmate.

Exploring the fragile emotional and physical territory that engulfs Kevin — and lends the book its title — The Year of Ice delves into family dynamics in the wake of the tragic death of Kevin’s mother, along with myriad issues in the life a teenager forced to hide his homosexuality. Though not a memoir, at the book’s conclusion Kevin’s future — like Malloy’s after high school graduation — remains unfocused.

What comes next? Malloy knows what happens to Kevin in his own imagination. He even included an epilogue in the original manuscript that jumps ahead twenty years in Kevin’s life. Though virtually every writer abhors being edited, Malloy is ultimately glad the epilogue was cut. “The book is community property now,” Malloy says. “I think the conclusion the reader comes to about what happens to Kevin is just as valid as mine.”

As for Malloy’s fate, he moved to Washington, D.C. after college in 1982 for two years of volunteer work, followed by two years working abroad before returning to Minneapolis and settling into a public sector career. He left behind close friends from his coming out period in Washington, though reasons for return visits were somber ones — funerals of those lost to AIDS — more often than not.

Now, at 42, Malloy finds himself in Washington for a much happier occasion: a public reading to promote The Year of Ice. And though torturously hot, a summer afternoon spent chatting at a café on P Street, his old stomping grounds, assumes as comfortably familiar an air for Malloy as the frigid realm of his novel.

|

MW: The response to your book so far is that it’s quite different from other coming out tales. Did you set out to make something so markedly different?

BRIAN MALLOY: Kevin knows who he is and he hides it. That’s how he deals with it. A reviewer recently wrote “[The Year of Ice] is very different from the typical coming out story where it’s a sensitive loner who desperately tries to change himself to straight before” — I love this line — “moving to San Francisco to become the fabulous, famous homosexual he was always meant to be.” I haven’t read many books like that, to tell the truth. I did know that I wanted this to be about a family with secrets. People calling it a coming out book is fine, though Kevin doesn’t really come out. Calling it “coming of age” is fine.

The thing with “coming of age” is that I tend to associate it with sort of sensitive, naïve, sweet guys where something comes along and kicks them really hard in the ass, then they’re cynical afterward. Kevin is pretty much a cynic from page one. When a narrator of any book is eighteen years old, then “Bam!” — it’s “coming of age.” If I wrote it from the perspective of a 42-year-old, they wouldn’t say, “Wow, this is a midlife crisis book.” That’s what happens when the narrator is a teenager. I think that’s kind of unfortunate.

MW: As an eighteen-year-old high schooler with a girlfriend and at least one crush on a guy, were you able to call that “gay” and say, “At some point, I’m going to have to drop the girlfriend and come out?”

MALLOY: I thought what lay ahead for me was getting married, doing my best to have kids, and raising a family. That’s what I assumed I would do, even though I knew I was gay. Coming out did not seem to be an option.

|

MW: When did it become an option?

MALLOY: When I moved to D.C. I was working by Dupont Circle, and I’d just see these guys on the street. I was like, “I gotta do something about this.” It was partly the frustration of throttled desire. But it was also just being so goddamned tired of lying about it. It’s exhausting. After you come out, you just forget what it was ever like to be in and to expend so much energy protecting this public persona. I ran out of the steam to do it. The first bar I went to was Rascals. I did surveillance from Kramerbooks across the street to see who was going in and out. Then I walked around it several times. I finally went in. I don’t know what I thought I was going to see, but it was just guys sitting around having drinks. I didn’t know what to say or what to do, so I walked right back out again. I was like, “I need help to do this.” I picked up the Blade and signed up for a coming out group. It’s a good thing I did. It was a really good group of guys and we’re still tight.

MW: Had you acted on your sexuality at all prior to that?

MALLOY: Very tentatively. When I was in Minneapolis, I placed an ad in the alternative weekly. I met a guy. His name was Tom. God, I’m waxing nostalgic — I haven’t thought about Tom in a long time. He was just a really adorable guy. Tall, skinny, blonde Minnesota boy. Played the organ at church. I was sharing a house with a bunch of people. There were like thirteen of us of this one crappy old house. I think my rent was thirty-five dollars a month. Tom and I would sneak into my room and play romantic music with the lights out. I started panicking that people would put two and two together. So I broke up with him. He was as deeply closeted as I was, and he didn’t have anyplace we could go. It’s a shame. He was a really sweet guy.

MW: How fondly do you recall your early-’80s period here when you started coming out?

MALLOY: As I was saying to [a friend in D.C.], “Back in the day, you had yourself a time.” We’d go to the Frat House, then we’d go to Friends and have the old guys buy us drinks because we were so broke. Then we’d go to Badlands. We’d pay the cover to get in, but wouldn’t have anything to drink because we didn’t have any money. We’d just dance all night long. If we got really hot and needed water — they charged a dollar for a glass of water — we’d go in the men’s room and just drink from the faucet. We were pretty broke, but it was fun. I had three boyfriends at the same time. It was a riot. I had such a good time. I was out every night. I couldn’t do that now.

MW: If you could go back and do it all over again, would you?

MALLOY: You bet. It was that time in your life when you’re young and you’re broke, and being broke doesn’t really matter because you’re young and you think everything will work itself out. You’ve just come out. I was like a kid in a candy store. I was a huge flirt. My first boyfriend had a Harley-Davidson. Then I had a New Wave boyfriend who had streaks of gray through his hair, and we’d go to the 9:30 Club dancing. And I had a younger boyfriend, and I actually wound up going to his prom with him. He was a high school senior. I shouldn’t be saying this. [Laughs.] But he was legal age.

MW: Which high school?

MALLOY: Walt Whitman [in Bethesda]. He was eighteen and I was twenty-one. He asked me, and I said, “Sure, I’ll go to your prom.” Like that’s going to happen. So we rent the tuxes — ha-ha-ha. Then we go out for a nice dinner — ha-ha-ha. And we kept waiting for the other one to back out, until we found ourselves on the dance floor at a high school prom.

MW: How smoothly did that go back then?

MALLOY: The students were fine with it. It was the teachers who were very uncomfortable. We broke up not long afterward following a huge fight. I remember I slammed his car door so hard, I broke the latch and he had to drive away leaning over to keep the passenger door shut. It was one of those young, intense relationships.

MW: When did you decide you wanted to be a novelist?

MALLOY: I always knew I wanted to do write, but I didn’t put any of the work into it until about 1997. When I was kid, I had G.I. Joe dolls, and I started writing then about them. I mean, they beat the hell out of each other, but each one had a character profile — they all had back stories. Then in high school, it was short stories. In college I wrote a novella. After college, I needed pay off a lot of debt, so I just went to work and didn’t write for about sixteen years. When my brother was diagnosed with brain cancer, we had a long talk about dreams deferred. At that time, I was working downtown in Minneapolis in a very demanding job. It paid a ton of money, but I was always working. I said, “I got this offer from the Loft Literary Center. It’s four days a week. I’d be taking more than a fifty percent pay cut to do it, but it would give me time to write and I’d be around writers.” And he said, “Do it. Life’s short, we don’t know how long we have.” So I cashed in my 401(k), which you weren’t supposed to do, and bought the house so I wouldn’t have worry about a mortgage, and started working at the Loft. I immediately became, like, ten years younger.

MW: What has your experience been like in terms of getting the novel published? Have you been more or less fortunate than other writers?

MALLOY: I’ve been much more fortunate. It’s been very un-typical. I submitted the book to agents to try to get representation, and I couldn’t get an agent. I was rejected by every man, woman and child with a pulse in North America. Finally I decided I wasn’t ready to give up on the book, so I submitted it directly to St. Martin’s Press without an agent. I sent a query letter and the first chapter. It was in a pile of unsolicited stuff — they call it the slush pile — and an editorial assistant dug it out, read it and liked it, and made her editor read it. He requested the full manuscript, then he made an offer on it. He’s been there thirteen years and this is maybe the third time that’s happened in his memory. The only other person I can think of is Judith Guest. She sold Ordinary People to Viking out of the slush pile in the ’70s.

MW: Is your approach something you encourage other writers to try?

MALLOY: It’s really very tough for the un-agented and unpublished writer. I actually do a workshop in Minneapolis for writers who don’t have an agent and whose material has not been requested by publishing houses. With the consolidation of publishing, even though there are a lot of different imprint titles, if you follow the trail, a lot of them lead to Macmillan, which in turn leads to [the Verlagsgruppe Georg Von Holtzbrinck Media Group] in Germany, which in turn publishes one-third of all the English language books published each year. St. Martin’s is part of that, actually. What it means is that a lot avenues are closed. But it’s not impossible to have them look at your stuff. All I can say is, “It’s one step more likely to happen than winning Powerball.” Don’t let the odds scare you if you really have the passion and want to get published.

MW: What about small independent publishers? Are they viable in this day and age?

MALLOY: They’re viable and they’re more necessary than ever. That’s why I love Alyson and its niche in gay and lesbian lit. All the smaller presses really play an important role in bringing new voices into the marketplace that agents and houses deem not profitable enough. Some of the best stuff is being published by the smaller independent presses.

|

MW: St. Martin’s chose to market your book as general fiction instead of in its gay category. How do you feel about that?

MALLOY: Every writer wants as broad an audience as possible. At the same time, I read gay fiction. I remember going to Lambda Rising for the first time and buying out the store with what money I did have, and I got John Fox’s The Boys on the Rock, and Harlan Greene’s Why We Never Dance the Charleston, and Edmund White’s A Boy’s Own Story, and Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance. Those were all marketed as gay fiction — I knew they were for me. As a reader, I really appreciated that. I also felt some sense of community just being in a gay bookstore and buying gay writers. It was something to celebrate.

Time has gone by, and the big chains carry gay titles. But I think my heart’s always going to be in the small independent gay bookstore with gay titles marketed to gay people. At a lot of my readings, it’s straight women who come. For them, the interest is in the father-son relationship, the relationship between Kevin’s father and women in his life, and between Kevin and his girlfriend. More than once, I’ve had women come up to me and say, “You know, I dated Kevin in high school.” It’s kind of sweet. I’m happy when people get something out of the book, no matter who they are.

MW: Are there drawbacks, though? Is it missing any of the gay audience you hoped it would reach?

MALLOY: It’s interesting, I went into a gay bookstore in Minneapolis. They didn’t have it and they’d never heard of it. [Laughs.] I came in and I was like, “Where’s my book?” The owner said, “You sold a book?” So that’s the flip side of having it marketed as general fiction. Some of the gay bookstores aren’t aware of it.

|

MW: What about the future? How long do you plan to keep your day job?

MALLOY: Until the day I drop dead. I’d like to live a life of leisure immediately, but it’s just not in the cards. Most novelists are working their day jobs and writing when they can. My goal is to have a career in writing where there’s another book after this one, and another book after that one. I don’t expect to ever make a living from it. Most writers don’t, unless they teach and do a lot of freelance work for magazines and newspapers, and that’s a very stressful way of doing it. I like a day job that has health insurance and more stability to it.

For the writers who really make it — like Stephen King when Carrie took off in a big way — that’s great. But it is a bit like winning the lottery. It’s a matter of a book getting into the hands of a person who falls in love with it and really becomes a champion of the book. Tom Clancy hit it big when Ronald Reagan picked up his book and loved it. Then Reagan’s circle all read the book because the president was reading it. Then the circle that wanted influence with the circle started reading it, and so forth. I thought of Reagan as the Antichrist — I still do — but he certainly helped launch Clancy’s career.

I would love to have writing be just what I do. That’s my dream world, where I wake up, and it’s me and the keyboard. Make a strong pot of coffee. When I need a break, I take the dogs for a walk down by the Mississippi River. Come back, write some more. It feels very genteel — a very classy way to live your life. That’s my dream — to have enough money to do that. But it is a dream.

MW: Do you want to continue contributing to gay literature?

MALLOY: There’s always going to be a gay component to anything I write. Part of it is that I’m most comfortable writing that, but part of it is that we are everywhere and we are in every story. As a writer, whether you’re gay or straight, you just need to reflect that reality.

Brian Malloy’s The Year of Ice (St. Martin’s Press, $22.95) is available at area bookstores.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!