DeBoldly Going

Kathleen DeBold's Mautner Mission

Susan Hester calls Kathleen DeBold ”Mautner’s Miracle.”

”She thinks about the Mautner Project in every waking hour,” marvels Hester, the lesbian health organization’s founding executive director and partner to Mary-Helen Mautner, whose struggle with, and ultimate death from, cancer inspired the 15-year-old organization, which will celebrate with its annual gala at the Washington Hilton on Saturday, September 17. ”Everything that happens she puts through the filter — how can this be helpful to the Mautner project.”

Since taking the executive director post six years ago, DeBold has grown Mautner into one of the country’s most important national organizations for lesbians. Its primary focus remains health — though it has broadened the mission to include more than ”lesbians with cancer” — and it still operates a local support, services and referrals hub that, as DeBold notes, informs everything the group lobbies for on a national public policy level. But its roots remain in the caring.

”One of the things that I love best about the Mautner Project is that the founding mothers created a community of caring,” says DeBold, ”a community of women who said ‘I’m here for you no matter who you are.’ We now have people who are clients, who have survived cancer or are surviving partners, and they come back and give back to the community to help people through what they went through. And it’s touching and it’s just so powerful.”

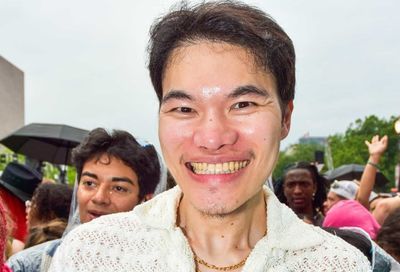

Kathleen DeBold |

A tough cookie with a soft center, DeBold is blessed with a speaking voice as mellow and rich as any late night DJs. But don’t let that fool you. She’s no-nonsense in her head-on approach to not only lesbian health concerns, but bigger-picture issues, such as advocating for a smoke-free world. Her drive to raise awareness is always in full gear — and she often finds ways to, as Hester notes, filter everything she discusses through Mautner.

”She’s a person who maximizes every opportunity,” says Hester. ”She figures out how to do it. And she’s done a powerful job of expanding our base of support locally and nationally,” including an ”incredible outreach to gay men.”

Basically, says Hester, DeBold is ”a person who sees the really big picture and at the same time pays attention to the smaller details.”

DeBold is, not uncharacteristically, more modest about her contributions to Mautner.

”I have been blessed with an ability to surround myself with good people,” she says. ”And somehow, those people gravitate towards me. And if they gravitate towards me, they’re gravitating to the Mautner Project.

”I feel that I am fulfilling Mary Helen’s vision,” she continues, ”building on everything that Susan Hester and the founding mothers created. But I don’t like to see ‘I’ because it’s such a ‘we’ organization. I think we’re really making huge differences in the quality of health care available to all people.”

METRO WEEKLY: Let’s start with a general overview of the changes and growth in Mautner from the time you started six years ago until today.

KATHLEEN DEBOLD: When I started, we had four staff members, now we have eleven. We had no intern program and now we have a great, dynamic intern program. We had no social workers on staff, now we have three, as well as a Masters of Public Health going for her Ph.D. So the staffing level is up, the professional level of the staff is up, the diversity of the staff has increased tremendously.

When I started, we began a real strategic growth that would expand the Mautner Project so that women who didn’t have access to our kinds of services and support locally would get them through us. We began to increase the training and capacity building for all the members of the Lesbian Feminist Cancer Coalition, and then we formed the National Lesbian Feminist Health Coalition. A lot of the groups were much more issue-specific [then] because the whole lesbian health movement had grown out of the lesbian cancer movement. [At the time] cancer was the issue that was so visible and affecting us so much.

MW: The mission expansion speaks to the name change from The Mautner Project for Lesbians with Cancer to The Mautner Project, The National Lesbian Health Organization.

DEBOLD: We wanted the name to reflect what we do, but we also did not ever want to lose touch with our past and our roots. The Mautner Project [started as] a local volunteer-driven direct service orientation in honor of the woman who gave us the vision, Mary Helen Mautner.

MW: You’re in a unique position in that you serve both a local and national constituency. What are some of the challenges of that?

DEBOLD: Our local direct services inform and inspire everything that we do. Every single day we are helping lesbians in crisis on a one-to-one basis. And seeing that and feeling that and going through the challenges with them makes the national work — advocating for lesbian inclusion in research, training health care providers, advocating for lesbian health issues with policy makers and politicians and the press — so much more real to everyone here. It gives us a community base, an instant feedback so that we can evaluate and improve what we’re doing. Also, it is absolutely crucial, because one of our main functions is to help grassroots groups do this work. So by modeling and developing programs here we can keep other groups from re-inventing the wheel.

|

MW: What type of services do you currently provide to people?

DEBOLD: We have all kinds of support groups. Bereavement support, for example. One thing in the lesbian community is the phenomenon of being invisible widows for lesbians. Many women, because of the closet, lose their partner and can’t share that at work because they’ll be discriminated against. Many of them are not even out to their parents, so here they are grieving in isolation. Our society is set up so that we help other people through grieving at work or in the community and even neighbors. And there’s a big difference between how someone relates when you say, ”Oh, my friend died, I’m really sad” and ”My husband died.” It’s two different images for a lot of people. I was just talking to one of our volunteers who lost her partner and she said she was at the hospital the night her partner passed away. The next morning she was at work as if nothing had happened.

Groups aren’t for everyone. People grieve differently. So we also have peer support for people who don’t want to come to a group or can’t come to a group or people who are in some small town somewhere, like Topeka, where there isn’t a lesbian support group, and they can be hooked up with someone who has gone through it before, someone who has lost their partner.

MW: What other types of programs do you have?

DEBOLD: We have a support group for everything, whether it’s people who are newly diagnosed with cancer, people who are cancer survivors, people who are caregivers. There are very few support services that are lesbian friendly, where people can feel absolutely safe.

We’re also doing the big picture work — training providers to be LGBT friendly, which is one of our biggest and most successful programs. We developed our cultural competency program, which is really sensitivity and diversity training, in collaboration with the CDC. And we’ve been doing it for years, constantly building, expanding and improving it. Right now we’re developing an elder care module and are going into nursing homes and assisted living facilities and training people there, because one thing that is happening is that, as our community ages, a lot of people are going back into the closest when they go into assisted living. Women who fall in love and are found in the same bed in the nursing homes are punished. There are all kinds of horror stories because people don’t understand. What we do is train the staff and the volunteers on dealing with this.

MW: What do you do when you find an instance where it is very clear that there is an inappropriate or homophobic reaction from a doctor or a health care provider? What steps do you take?

DEBOLD: It’s interesting because we’re working on a case now with NCLR where a woman came to us and said, ”I went to my doctors to get a prescription for bronchitis and my doctor wasn’t available. I saw the other guy and he said, ‘Oh, yeah, I’ll leave the prescription and a packet of information.”’ She took the prescription to the drug store, opened the packet, and it was full of scriptural references to homosexuality being a sin, religious tracts and information on ex-gay ministries. That’s a clear violation of the patient’s bill of rights, but there is nothing that can be done about it because there is no legislative protection. You know, sometimes things are clearly wrong but if there is no legislative remedy and if the local medical association isn’t educated and policing their doctors and responding to complaints, nothing will happen. So we immediately called NCLR and are working together filing complaints on this woman’s behalf — this very brave woman, by the way, because this happens a lot and people are afraid to say anything.

MW: Why is that?

DEBOLD: When you’re at the doctor’s you’re often at your most vulnerable — you’re usually sick, you might be sitting there naked, and then you’re assaulted with this absolute breach in trust. It’s absolutely shocking.

MW: In the best of all possible worlds, the doctor does not judge. A doctor takes the information and says, ”Okay, I’m dealing with a gay patient, a lesbian patient…” So it must be really upsetting for a patient to suddenly feel as though they’re being judged.

DEBOLD: It’s tremendously upsetting — and it’s also incredibly harmful because research shows that lesbians go to the doctor less often than their heterosexual counterparts, and one of the main reasons for this is because of bad experiences with doctors. The minute you walk into a doctor’s office you often know that they’re not savvy about who you are or inclusive — it says, ”Single, married, divorced” on the form. It says ”Are you sexually active?” I always put things like, ”No, I just lie there” or ”Well, it depends on if I’m on top” or ”The five of us take turns.” I try to change it just so that they’ll wake up and I can educate them. Then I go, ”You know what? A better way would be to say ‘are you sexually active with men, women, both?’ ”What are your sexual practices?” Lots of times they don’t ask ”Do you use birth control?” They’ll say ”What form of birth control do you use?”

|

MW: We live in a society of assumptions.

DEBOLD: It’s heterosexist, and we call them ”heteroassumption.”

MW: Are we seeing progress?

DEBOLD: Yes. For example, we recently trained all of the CDC’s breast and cervical cancer early detection centers so that they are lesbian friendly. We’re working with a lot of the Planned Parenthoods. We’re working with medical schools, getting the future caregivers and letting them know right from the beginning. Of course, young people are much more open and savvy about the diversity of the world, so that’s been very good.

MW: Do you think we’ll see a major shift 20 years from now?

DEBOLD: Yes, if good people can keep the momentum going. I get very worried when I hear friends say, ”We’re moving to Canada.” Or people move off to a gay retirement community and consider that their gay activism. People need to be constantly vigilant and engaged. They need to give money. They need to come out to their doctors. They need to call people on homophobic practices of any kind. If our community can really make that personal commitment to changing the world, the world will change.

We’re also working with Lambda Legal because some lesbians were denied service by a fertility clinic because the clinic didn’t believe that lesbians should have children. There’s a big movement in the radical right, it’s called ”conscientious objectors” where pharmacists say they don’t have to sell condoms or they don’t have to fill prescriptions for birth control pills because it’s against their conscience. People are actually pushing these bills in their state legislatures. Again, this is why we need to be vigilant. Our health depends a lot more than the usual eat right, stay fit, see your doctor. It also means that if you’re an LGBT person, support your local gay rights lobby like Equality Maryland, for example, or Equality Virginia.

MW: What do you see as the greatest strength of the Mautner Project?

DEBOLD: I think it’s the history and the vision. It came out of the women’s movement and the lesbian movement. It started with a grassroots, volunteer-driven, very altruistic philosophy. Take care of yourself, take care of each other has remained the foundation of everything we do. But our strength lies in the larger commitment. It’s not just about cancer, it’s not just about lesbians. We see ourselves as a social justice organization, concentrating on health, with a focus on women who love women. And so the broader vision of social justice and health justice is part of everything we do.

The other strength is being strategic — there is so much that needs to be done and we have to be so careful not to over-commit ourselves or try to do too much because we’ve seen too many organization that have folded because they tried to do too much. We just don’t want to do that.

MW: What’s your greatest weakness?

DEBOLD: I don’t want to be crass, but it’s money. We’re tremendously under-funded. There’s millions of lesbians and we’re the only national lesbian health group, and we have like a $1.2 million budget. It’s heavily grant-funded — and it’s very hard to get grants in this political climate as a lesbian group. Lots of foundations realize the need for cultural competency training. They realize the need for access to care and they’ll put out requests for proposals saying ”We want projects that will increase access to care for medically underserved people.” But they don’t mean lesbians — they mean other minorities. So we have to work so hard to get in the door and convince them.

MW: Is it harder to raise private donor money in 2005 than it was in 1999?

DEBOLD: Yes, because of the political sea change. A lot of people have been saying to us ”We love the Mautner Project and we love what you do but we’re putting all our money into politics.” People are hit hard by the economy, which cuts down on their ability to give.

MW: Do you think there are too many organizations competing for the same dollar?

DEBOLD: No, I think that there are too many people who have not yet realized the importance of giving. I can’t believe since I came here how many people I’ve been able to bring in by just saying, ”Hey, listen to this. Does this sound like something you’d want to support?” And they’re right there with me. So a lot of it is getting the word out to the right people.

MW: Every organization seems to always be in crisis.

DEBOLD: The sexy things when people are giving is start-up — the excitement of ”Let’s build it, let’s make it happen” — followed by ”Oh, my god, we’re in crisis, help us out.” There’s such a sense of urgency in both of those messages. And they are urgent. But it’s also urgent to keep the doors open, to keep the phones on, to keep paper in the copying machine. And that’s not quite as sexy. A lot of times people think, ”Oh, yeah, you did that last year, but what are you doing now?” And that’s why grant funding is a double-edged sword — it’s usually not for general operations, which is the hardest money to raise. For example, we do a yearly audit. We’re very fiscally responsible. We have to pay for that. That’s not something where you send out a direct mail letter and say, ”Hi, will you please give us $10 towards our audit?” That’s not a big seller. But a lot of grants pay for projects, and they pay for a limited period of time, so you start things up and you might be able to get donors interested but sometimes they’re like ”Oh, yeah, that’s an old project. What have you got that’s new?” So a lot of it is just being much better at communicating and educating people about what it is we do. When you think about it, what’s better than taking care of people, what’s better than making the world a better place, making people healthier? It’s a wonderful thing and if we just communicate that correctly the people who have the ability to give and find that an attractive investment, will give.

MW: I want to ask you about the push for mandatory smoke-free bar and restaurants, which is major issue right now in the D.C. nightlife arena.

DEBOLD: We are in favor of smoke-free space [in the bars and restaurants]. Second hand smoke kills — that’s the bottom line. We would like people to have the opportunity to experience smoke-free space and realize how wonderful and different that is.

MW: But why shouldn’t it be left up to the individual businesses to make that decision?

DEBOLD: It’s like any employee protection thing. Most individual businesses would make a decision to save money if they didn’t have OSHA rules that protected employees. This is a protection for people. Smoke hurts people.

MW: But what about the customers? Let’s say, you have two bars, one smoke free, one not. The customer can then choose which bar he prefers to patronize. It’s the same argument that’s made with television. Just turn the channel. Just go somewhere else.

DEBOLD: I think people have the right to breathe smoke free air — I think that’s a human right. The tobacco companies have had all these years of smoke-full spaces to get their message across. I think it’s time we allowed people to experience smoke free. This is happening all over the country. People prefer it. People also have the right to say, ”We want everything full of smoke, let’s change it back.” We’ve done studies, we’ve surveyed people across the country and they will actually pay more of a cover charge to go to smoke free bars.

MW: Were you ever a smoker?

DEBOLD: Yes.

MW: For how long?

DEBOLD: A couple of years.

MW: How heavy?

DEBOLD: Not that heavy, on and off.

MW: So did you consider yourself addicted at the time?

DEBOLD: Yeah, I was addicted.

MW: When was this?

DEBOLD: When I went to Africa. I went to Africa for most of the 80’s and I picked up the habit over there and came home with it. Luckily, [my partner] Barbara said, ”Cigarettes or me.” So I cold-turkeyed it.

Look, all the doctors say smoking is bad for your health. Tobacco is bad for your health. That means chewing tobacco and spitting tobacco. And the Surgeon General came out with a tremendously comprehensive report on all the ways that it’s bad. It’s terrible for children. Tobacco companies spend billions of dollars fighting laws and trying to get people addicted. So it’s kind of an absurd thing that we’re all still discussing this.

MW: You spent years working at The Victory Fund. How is it different working in gay health arena as opposed to the gay political scene?

DEBOLD: With the Victory Fund, there were campaigns. And campaigns have beginnings, middles and ends. [Mautner] is like a constant campaign. It just goes on and on and on and on. With the Victory Fund, someone either wins or loses and then you move on to the next, are they going to run again, or are they going to run for a different office? But here’s it’s just constant.

There is also the reality that we deal with people who die — and that’s pretty different from losing an election. It’s something that I will never get used to. And I’m glad that I won’t. And you know Mother Jones [credo]: ”Pray for the dead, fight like hell for the living.”

MW: How has being the executive director of Mautner changed you as a person?

DEBOLD: It has made me a much more loving person and made me realize how much love there is. When I see the love between people and their dying partners, when I see the love in a circle of caregivers around one of our clients, when I see the interactions in the office, when I’m at the gala looking out and thinking ”My god, these are sixteen hundred people who care enough about other people to come out tonight and celebrate 15 years of taking care of each other,” that’s pretty overwhelming.

And that’s one thing I really, really love about our movement: When you think of what we are working toward, all the words come out justice and equality and health and fairness. I mean, those are all the right reasons to be doing what we’re doing.

The Mautner Project’s annual gala, auction and dance will be held on Saturday, September 17, at the Washington Hilton. Tickets are $160. For more information on the gala or any of Mautner’s programs, call 202-332-5536 or visit www.mautnerproject.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!