A Bugg's Life

From racy prose about his rowdy youth to sober takes on more serious matters, Sean Bugg wrote his way to an unexpected adulthood

Sean Bugg used to be the guy I’d run into on the corner of 17th and Q as friends and I made the stations of the weekend cross: JR.’s, Cobalt, the long-gone Trumpets, which flourished for a while in the downstairs space where Chaos later reigned.

Sean Bugg

(Photo by Julian Vankim)

Now he’s the guy my other half and I run into at Tysons Corner on a Saturday — shopping for a wing chair at Arhaus before a 7:30 movie, rifling the racks in the men’s department at the Nordstrom half-yearly sale. How the mighty (flighty) have … settled comfortably down.

In some ways that’s the defining arc of Boy Does World, Bugg’s new collection of essays. It’s drawn partly from the archives of a long-defunct Metro Weekly column called ”The Back Room” — firsthand, first-person observations on D.C.’s 1990s club scene, with regular excursions into associated bedrooms, bathrooms and back rooms — and partly from Bugg’s more recent Op-Ed pieces, on topics from the pleasures of introversion to the politics of marriage equality to his own husband, Cavin Le, and the home they’ve made for themselves. (It’s in the same Virginia suburbs, ironically, that he once poked fun at in print.) By turns the collection is cheerfully smutty, energizingly ornery, surprisingly sentimental.

No, not quite sentimental. Earnest. Though Bugg would probably squirm at the word.

The book is also a kind of a professional cross-section of the man. You see him stretching as a writer even as he grows as a person; the columns progress from flashy if sometimes facile riffs on the week’s mischief to more artful, more thoughtful meditations on more pressing matters. Among the finest is “Stuck in the Middle,” an archly footnoted confession of midlife crisis written a decade ago; it frames its insights with a mature journalist’s mordant wit, though it’s not afraid to employ a few of the brassy youthful flourishes that helped Bugg land his gig.

An editorial note, if only because it’s a little unusual to be the guy who profiles the guy who runs the magazine: Metro Weekly co-publisher Randy Shulman invited me to interview Bugg, whom I’ve known casually, if mostly as a colleague, for 15 years or so. (Though I did attend his wedding reception.) No questions were submitted in advance. No topics were deemed off-limits. And Bugg acknowledged at the outset that I’d have to agree, before the fact, to any requests he might make to go off the record; there’d be no shooting himself in the foot, then asking me to apply a tourniquet. So if you’re just here for the wrathful recap of that unfortunate Fishbowl D.C. incident, you can save yourself the trouble and move along to this week’s Coverboy interview. Like you haven’t read it already.

If, however, you’d like to spend a little time with a fellow you may think you already know — a Kentucky boy who loves the city but misses the country, a man who spent a half-decade talking about sex in public but who thinks of himself as shy, a confessional writer who’s reluctant to say too much about the people and the things that really matter to him — by all means, let’s get started.

METRO WEEKLY: So you’ve got a magazine. Why a book?

SEAN BUGG: The honest answer is that it sat around for a really long time, and I had a lot of people telling me, “You really should put this stuff together.” And I needed to check something off the bucket list. It’s like the unfinished project of my life to actually get this thing out.

MW: How much of your real self do you find now in those early columns? And how do you feel about that guy?

BUGG: More than you think. I’ve always had people ask me this. “Did you exaggerate, did you make things up?” You always exaggerate a little bit for humor. But I never regret anything that I’ve written. I certainly don’t regret most of the things that I’ve done. I did tell my mom and my sister both, “Well, what you should really do is read it from the back, and when it gets to the point where you can’t take it anymore, then you can stop.”

MW: I’m just going to guess that one potential stopping point is going to be at the line, “Because I was out of Mrs. Butterworth’s.”

BUGG: Yeah, that might be more than my sister can take. Maybe even more than my husband can take. He hasn’t finished the book, either. The funny thing is, I remember writing that line. I still remember the specific moment, and who it was. It involved a soldier who was a friend of another soldier boyfriend of mine, and it was very complex at the time. There were deeper stories behind some of those things.

MW: For people who moved to the city more recently or who haven’t always read Metro Weekly, explain what ”The Back Room” was.

BUGG: ”The Back Room” originally was supposed to be a straight-on sex humor column. I wrote this little essay about my first time buying a dildo, which I wrote while I was sitting around in the afternoon, searching for jobs and sending out résumés. I sent it over to the other gay publication, and they rejected it because they thought it was too tawdry.

MW: But then Randy Shulman got his hands on it?

BUGG: Somehow or other he got a copy of it through mutual friends. The idea at first was that ”The Back Room” would be rotated among different writers, but then nobody else was young and — my ego wants to say “fearless enough,” but actually it’s just “young and stupid enough” — to do that kind of thing. So I ended up doing it every week. And it was mostly just to fill up that back page, [but] it became kind of a standing attraction for the magazine.

The amazing thing for me was, I moved here specifically to be a writer, to be a journalist, and that unemployed period where I wrote the dildo column was where I was trying to figure out, “What the fuck is it that I actually want to do? Do I actually want to be involved in this industry?” So it was actually really, really cool to be writing, and to have people know me as a writer. You’re a writer — I think there’s a certain thrill every time you’re recognized, or every time somebody says, “I read what you wrote.” I love that.

MW: I used to refer to it as “the wan limelight of the byline.”

BUGG: I’ve loved that ever since I was a kid. It was really great to finally kind of get something that I’d always wanted, which was to have people say, “Oh, my God, I know your name. I can’t believe you wrote that.”

MW: Did you realize that you were jumping into the deep end with a weekly column and a weekly deadline?

BUGG: No, not at all. And when you do something like that every week, you’re going to write some real stinkers on occasion. So I left those out of the book, mercifully for everyone. But, yeah, I had no idea. That’s why it turned into writing about Granny back in Kentucky — because I had a fairly interesting life, but it wasn’t that interesting.

MW: I would imagine that the discipline came in handy when you started writing about things like cars and politics.

BUGG: Yeah. Being able to just sit down and do 550 to 800 words on any topic that anybody puts in front of you is one of the core skills in journalism. And it’s funny that I really hadn’t had that experience in D.C. I had been doing stuff like covering stupid taxes. I was a tax reporter for six hellish, brutal months when I first came to D.C. Have I ever told you this?

MW: You have not, in fact, and I’m not sure I believe it.

BUGG: Prentice Hall Information Services. Back in the early ’90s. It was really cutting-edge technology: Every morning, these businesspeople would get a fax [from PHIS] with the latest information on taxes. So I was responsible for pulling that information together, running to the IRS building every morning and picking it up — because you didn’t get forms on the Internet in those days. It was the most boring crap ever.

I got promoted because I actually was good at it — but I got promoted to covering the Securities Exchange Commission, and I had no fucking clue how the New York Stock Exchange worked or anything else. And I would go to these briefings at the SEC, and I had no idea what the hell they were talking about. So that didn’t last very long before I was ushered out the door to find other employment opportunities — which is one of the things that led to that whole early-on career crisis.

MW: But there’s a difference between reporting a story and writing a column that has a voice.

BUGG: And the interesting thing is that I grew up thinking that I wanted to be a reporter. I grew up on — do you remember Lou Grant?

MW: Sure. Mary Tyler Moore spinoff. Ed Asner as an editor at a big-city daily. But I didn’t watch it a lot.

BUGG: I watched it all the time. I loved that kind of stuff, and I thought that that was what I wanted to do. The SEC thing kinda taught me that it really wasn’t what I wanted to do. When I started writing columns, that actually freed me up a lot.

MW: There are traps that columnists can fall into, too, though.

BUGG: I had a really bad habit when I was writing ”The Back Room,” in particular, of writing to the headline — a lot of times, what would come to me first is the headlines. “Impaled on a white picket fence” was a phrase that came to me, and then I wrote a column about it.

MW: There’s one headlined ”Bad Trips,” about the horrors of a hookup with someone who lived beyond the Potomac. We’re sitting in the living room at your house in Falls Church now.

BUGG: I was kind of a dick about that stuff when I was younger. Though believe me — going to Leesburg for a trick when you’re 20 years old….

You know, I still struggle with living in the suburbs, because I actually love D.C. I grew up on a farm; I grew up knowing everybody. You could see a car coming down the road a mile away, and you’d know from the sound of it who it was. Every time you’d go down the street, you’d see people you know, and people recognize you. In D.C., in the gay community, it is a very, very small town. That drives some people up the wall, and those people all go to Miami and New York. For me, it’s very comforting.

But living in the suburbs is much better than I thought it would be. I only moved here because my husband wanted to, and if you’re lucky enough to find somebody who can put up with you, you’re going to do what they want as much as you can.

MW: There are probably some of your friends and acquaintances who think of you mostly as the guy who edits the magazine. There will be people who don’t know about this part of your career writing these mildly naughty columns.

BUGG: Naughty is a good word.

MW: And there may be some people who do remember that phase, and will be surprised to learn that you are now this suburban guy with the husband. I wonder if there are a lot of people who will be surprised to hear you use words like “shy,” which you use a couple of times in the book, and “comfort,” which you’ve just used to describe the way it is in a small and close-knit community of people.

BUGG: I actually am a really, really painfully shy person. That tends to surprise people because obviously…

MW: You’re also kind of a smartass. And you can be a bit of a hardass — I don’t want to say “brawler,” not physically at least — but you’ve been known to pick a fight.

BUGG: Yeah.

MW: So “shy” and “comfort” may surprise people.

BUGG: I think that’s only because of what I try to put out as a public persona. I mean, I’m far less shy when I’m writing. I can share things that I think would horrify other people to say. I think it’s because I have control over it. It seems very exhibitionist — it seems very open, the antithesis of shy. But I have a lot of control over it, and there are a lot of things I didn’t say — there were a lot of things about the inner emotions that I don’t share.

It’s actually kind of funny because when you use a term like “hardass” with me — I know I’m a smartass, because I don’t really take many things from people particularly seriously. I think most people who think they’re smart, aren’t. I think most people who think they’re something, generally aren’t. I don’t think I’m particularly smart either. There are very few people that I actually consider smart and talented and worthy of me thinking that they’re smart and talented. I think the rest of us tend to be struggling to be better than we know we are. That’s so fucking pretentious!

MW: Impostor syndrome, right? I’ve always taken that as a sign of at least moderate intelligence. Not a day goes by that I don’t think somebody’s going to find me out as someone who’s pretending to be good at what I do.

BUGG: Probably the hardest thing about putting that book together was going back and re-reading my stuff, because familiarity really breeds contempt when it’s your own work. I don’t know if this is the kind of thing you want to say to sell books, but it’s painful for me to read the earlier stuff. Because even though I can recognize that it’s funny, and I’m happy that I wrote it, I know that I would write something completely different today.

Stuff I do can end up being like a pale imitation of my particular heroes, but I know that I’m fairly good at what I do. I make a living at what I do, and there’s a reason that I make a living at what I do. I’ll be honest: I actually do think that I’m a better writer than most of my contemporaries. That’s kinda dick-y to say, but as critics and as readers and consumers of culture, we all know that 90 percent is shit and 10 percent is good.

MW: You don’t think, maybe, that 10 percent is good, and 90 percent is on a continuum from shitty to okay?

BUGG: You’re kind. [Laughs.]

MW: Maybe what I mean to say instead of “hardassed” is that you go from 0 to 60 pretty quickly.

BUGG: I’m actually generally somebody who’s always going to look for the quiet way, the happy way. I don’t like yelling; I don’t like being nasty. But once it gets to a certain point, it’s kinda like everything falls away, and then I just become as nasty as shit. I’ve always said that I have my mom’s temper but my dad’s control. I can really hold my temper beyond what most people can, but once it breaks it’s like, God fucking help anybody who’s in my way, because it really breaks.

I’m not actually that expressive a person in ways that matter to me, if that makes sense. The reason it’s so easy for me to go to a sex joke, or to talk about things that I did in the past, is because it’s easier for me to talk about that than it is for me to talk about — for lack of a better example — why I love my husband. That doesn’t expose me, because that stuff doesn’t matter to me.

I think that’s what confuses people about me sometimes, because people’s sexual behaviors tend to be the things that make them clam up or get quiet or go in the closet. Those are the things that tend to make people uncomfortable. I don’t care about that. Things that make me — this is going to sound so fucking pretentious — things that make me kind of ache on the inside, things that make me just really kind of impossibly happy, those are things I want to keep to myself. I don’t mind being judged on sex. But I do mind being judged on those kinds of things, the important things.

MW: Not everyone has read the book, and not everyone will, so briefly: You’re from Western Kentucky?

BUGG: Fredonia, Ky. This little bitty town, not even the county seat — I think it was maybe 1,000 people, if that. It’s probably more like 800. The rest of the family were farmers. I grew up with fields behind me, and to the side, and everything belonged to various family members. My dad had an auto body shop, so I grew up working on cars. Cars still mean something to me, just because of the way I grew up but I also grew up knowing that — well, when did you know that you were different?

MW: I remember in sixth grade being intensely conscious of whose locker I was sharing, and who was in the locker next to me.

BUGG: I was getting ideas in third and fourth grade, pretty early on. I was reading from an early age about stuff I shouldn’t have been reading.

MW: You passed around romance novels. But you talk about one particular book that you kept.

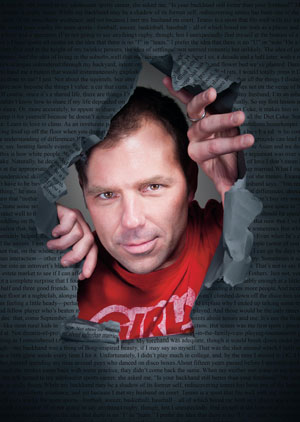

Sean Bugg

(Photo by Julian Vankim)

BUGG: The Boys in the Mailroom. Iris Rainer. It’s basically a tawdry, tawdry fucking novel. There’s a scene very early on about a bunch of 12-year-olds at a party, and they play the game “Two Minutes in Heaven.” They tease one boy by throwing another boy in with him, but he ends up giving this 12-year-old a blow job, or something. I’m not sure anybody would write that anymore, because you’d have the Justice Department on your doorstep.

MW: I remember the thrill that came from discovering the novels of Gordon Merrick.

BUGG: [Laughs.] I think where I was going with that question was: There were definitely expectations of how I was supposed to turn out. I have an older cousin, Brent, about six years older than me. My family will all die of embarrassment when they read this, but he was just like this golden god in a lot of ways, and I always felt like this was what I was supposed to be. I always knew that I wasn’t.

Brent got married, and I was an usher in his wedding, and he did everything perfectly and he was exactly what everybody wanted him to be, and it came naturally. I didn’t want to be that. I didn’t want to be a farmer, I didn’t want to be a banker, I didn’t want to be a car-body repair guy, and — I don’t think I wrote this in the book — I went to my dad crying one day because I thought that he wanted me to take over his business, and it finally got to the point where I was just traumatized by it. “I don’t want to do this.” And he said, “I don’t expect you to do this. I expect you to do what you want with your life.”

MW: How old were you?

BUGG: I think I was in fourth grade. It might have been fifth. It’s hard for me, because I love where I’m from. I love my family and I love that part of the country in a lot of ways, but it’s also something that I can’t be a part of.

MW: It’s easier to love from a distance.

BUGG: In some ways, yeah, but it still hurts actually to be at a distance. There’s something that I don’t get out of life that other people in my family did because they got to stay close and they got to keep those relationships. And it’s weird how that still hurts after 20-odd years. But you know, I take Cavin home for Christmas. He comes home with me every year at least once, and everybody is perfectly pleasant. We’re born and raised Southern, so you’re polite, but there’s a distance. I know the first time I brought Cavin home, it was kind of a shock — because I even joked that the Asian population in Kentucky goes up by at least 2 percent every time he crosses the border. And I know that we’re never going to be viewed the same way as my sister and her husband are.

MW: Is any of this connected to what we talked about earlier? The imposter-syndrome stuff?

BUGG: If you’re spending a good portion of your life constructing a persona that hides certain things about yourself, be it that you’re gay or be it that you’re not the good son that you think your parents want you to be, I think yeah, you do get to a point where you always believe that there’s going to be a disconnect between what people see and what you actually are. I always want people to see me as intelligent and witty and all these other kind of things, but still I don’t feel that way.

God, it’s depressing! Nobody is gonna buy my book now. Thank God you’re asking questions about things other than blow jobs.

MW: You’ve published a lot of interviews of this sort. What’s the question you most don’t want me to ask?

BUGG: There are a lot of candidates for that. [Laughs.] Probably I would be hesitant to answer — but if you asked it I would — about exactly how self-destructive my behaviors were when I was that age, when I was doing that kind of stuff.

MW: In the ”Back Room” columns?

BUGG: Yes. I’ll just throw that out there and see where you want to go with it.

MW: We’re both about the same age, right?

BUGG: I just turned 43. We’re certainly contemporaries.

MW: You’re older than I am. When did you move to D.C.?

BUGG: June 1989.

MW: We’re actually almost exactly the same age, and we came to D.C. from small towns within six months or a year of each other. To me, that meant that I had grown up just late enough, and gotten to the city just late enough, to miss the horrible years, and that I’d learned just enough to keep myself alive.

BUGG: Right. I mean, I consider myself really, really fucking lucky. When I first came to D.C., sex was a very important part of who I was as a young gay man. Whether that was a pathological need or not, I don’t know. But I built a lot of my self-identification as a gay man around being wanted by other people and enjoying sex. Sex was fun. But, you know, when you and I moved here, and when we were just coming up, sex was also really, really fucking dangerous in a lot of ways. And I didn’t always make the right choices.

But I got out of it. I think if there is anything — I don’t really regret anything that I’ve done — the only thing I regret is that there are people that weren’t as lucky as I was. Or maybe I was lucky enough to make the wrong decisions at a time when it didn’t have as big an implication. Other people made the same decisions with somebody where it had a lot more repercussions.

That’s the hardest thing for me, the feeling that — God, this is so morose, and actually kind of narcissistic at the same time — I always felt like I was going to be one of those people. I always thought I’d be one of the people who died. Because in a lot of ways that’s what we were told when we were young. To be gay in the ’80s was to get AIDS and die. I had a cousin who moved to Atlanta and came back to die, very quietly. And as my grandmother told me, “You know he went blind before he died.”

That’s why, going back to what we talked about earlier, why am I talking about comfort? Why I talk about acceptance, if I even used that word? And why I look happy living in the suburbs? I’m so fucking lucky to be able to do that. It’s hard for me to even express how fortunate I am to even be able to experience it, and to have somebody who’s far more stable than I’ve ever been, and who can put up with the fact that I’ve been through all these different things. You and I have very similar life experiences. Cavin and I have radically different life experiences.

MW: The book ends with you here, cooking Thanksgiving dinner for your extended family, with Cavin and your in-laws. So I don’t want this conversation to not include some specifics about your partner and his family. Give me the short version of how that came to be.

BUGG: It was very ”sitcommy” in a lot of ways. After I got out of the early ”Back Room” phase of my life, I went through this kind of transition, figuring out what I wanted to do and how I wanted to structure my life. One of the things I did was start to play tennis again, and I got involved with the local gay tennis group. I dated a couple of people within the group, because we’re gay men and that’s what gay men do, and I dated another guy — this will probably cause all kinds of drama, saying this — another guy who was Vietnamese. And we were all friends, me and this guy and Cavin and a number of other people, and when that relationship broke up, we were all still friends. But I had this horrible crush on Cavin that went on for months, because I just didn’t know what to do with it. Always sitting in the room and just kind of mooning, because we’re friends and he’s friends with the guy I used to date.

But I finally got up the nerve to ask him out and it all kind of worked out. That sounds so boring, doesn’t it?

MW: Well, considering that you used to make a living writing about how to snag a guy in a bar or at a sex party…

BUGG: I was never able to write about how to keep them.

MW: What would you write now — serious advice about finding somebody who matters?

BUGG: Be ready for it. I was trying really hard for something I wasn’t ready to do. That’s why some of the relationships I’ve had in the past didn’t work out — because I wasn’t quite ready to leave behind a lot of other stuff.

You know, that sounds really trite. I don’t know. To be honest, I wouldn’t write a fucking advice column now. I just wouldn’t do it, because I think writing advice columns is one of the biggest scams out there. Nobody actually knows any of this shit. Nobody can tell anybody how to live your life. Nobody can say, “This is exactly what you need to do,” or “You have this crush on this person and this is how you should react.” The only thing you can do is experience your life, figure out what you fucked up, figure out how not to fuck it up the next time and then see if you can move forward — knowing you’re going to fuck other stuff up.

MW: You just undermined the small industry that is Dan Savage.

BUGG: You know, Dan Savage is Dan Savage. Not to disparage Dan, but…

MW: I actually meant to turn that around, to turn it into a question. Something along the lines of: You cite Miss Manners a few times, and P.J. O’Rourke. Are there other smartass writers you admire?

BUGG: Miss Manners doesn’t get enough credit for being the smartass that she is. She is a horrible smartass. And not enough liberals read P.J. O’Rourke. If you go back to his old stuff — I never would have dreamed of writing that old piece about why you should never give your cat cocaine.

MW: Are there other writers you like?

BUGG: David Foster Wallace. What amazes me about him, other than just the raw talent, is that somebody who obviously was so depressive and so mentally troubled could be so funny. He taught me that you don’t have to be ashamed of not being ironic. You can actually feel things and believe things and express those things. That to me was a real revelation in terms of how I experienced literature, how I experienced other writers.

MW: I have a colleague who likes to point to the popularity of Glee, and to celebrate the relative success of Jimmy Fallon in his late-night gig, as evidence that the public appetite is turning toward exactly that — a sort of understanding that a little bit of joy is necessary, and that it need not come with commentary.

BUGG: To some extent I would kind of agree with that. On the other hand, after 9/11, everybody proclaimed the death of irony, and look where it got us. Living life without irony when you can do that is important, and that’s why I say Wallace is important. A straight-on, non-ironic approach to life in all situations? I’d claw my eyes out. I would not be able to suffer that. But feeling — just feeling — is a valid thing. You don’t have to have an excuse for feeling.

MW: You don’t have to be unmoved by everything.

BUGG: And if you are unmoved by everything, really you’re kind of a sociopath. There’s a good textbook definition. Sorry, Larry David.

MW: Let’s talk business. If the price of newsprint were to triple tomorrow, what would you do with yourself?

BUGG: Go online. [Laughs.]

MW: Wait, didn’t I read in Fishbowl D.C. that you did that?

BUGG: The high school yearbook of D.C. media.

MW: Yes. Sometime ago, they announced the sudden demise of Metro Weekly.

BUGG: They announced that we were going online only in three weeks. That was about two years ago, and I think we’ve proven that we’re not going online only. The Fishbowl thing was bullshit. Everybody in this business goes through that sort of thing, so everybody in print has had their demise predicted multiple times. And for a lot of us, it hasn’t happened.

MW: Okay, then, what would you do if you couldn’t do this?

BUGG: Not catering. People ask, ”Are you still catering?” And I’m like “no.” I loved doing that. But it’s really fucking hard to make money as a one-person catering outfit. Not something I would recommend.

MW: What haven’t I asked you that I should have?

BUGG: “How much do you love your husband?” I don’t know — is there anything that you were afraid to ask me?

MW: Not especially. I should probably ask about what appears to me and to other people to be bad blood between Metro Weekly and the Blade.

BUGG: Actually, I think that might be an off-the-record conversation.

MW: Hmmmm.

BUGG: On the record, it’s all fine. [Laughs.] Like most other cities, it’s a pretty competitive media market. We all do throw a lot of sharp elbows from time to time. I think that regardless of what we all may think of each other, we’re all pretty passionate about what we do.

I’ll say this: I’m really, really proud of what we’ve accomplished at Metro Weekly. And even taking into account the whole meta, narcissistic nature of this entire conversation, we’ve done something that very few other people in the country have been able to do, which is to launch a gay publication and keep it alive for more than two or three years. I mean, we’re 17 this year. To last five years is amazing. To last 17 years in a city that already had what was once the nation’s premier LGBT publication, I’m pretty fuckin’ proud of that.

MW: You were a member of ACT-UP back in the day. If you were going to be activist about anything now, what would it be?

BUGG: If I’m going to be selfish, marriage. If I were smart enough to go outside of myself a little bit, I would be working on transgender issues. I don’t think LGBT issues are all the same. But they’re related, and I think that based on our own experiences — gay, lesbian, bisexual people — we need to put a little more into that. If there’s anything that Metro Weekly has taught me, that’s it. The number of stories I’ve had to publish about transgender people being killed, that should give everybody pause.

That’s the thing I hope I would be working on. What I will probably be working on is marriage, because I’m a self-involved, selfish person. Like everybody.

Boy Does World ($22.95) by Sean Bugg is available on Amazon.com and at select bookstores.

Trey Graham is a theater critic for the Washington City Paper and an arts editor at NPR.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!