The Name of Life

Alison Smith's lesbian memoir ''Name All the Animals''

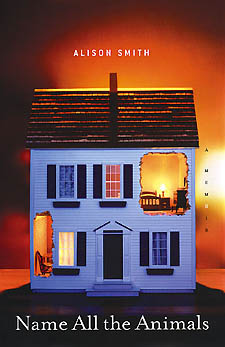

It’s tempting to present Name All The Animals, the new memoir by Alison Smith, as a series of suggestive clichés. Imagine Catholic schoolgirls in plaid skirts, knee-highs, and buttoned blouses watched over by stern but loving nuns. Watch them gossip about graduation, who will make the “Virgin Court, ” the girl-whose-brother-died, and, naturally, lesbian love. Fun? Sure. But it would also be a serious disservice to the lovely, heartbreaking truth of Smith’s memoir, or the soft-toned accomplishments of the book.

Name All The Animals begins with the dual events of Alison’s first period and her brother’s sudden, accidental death, and ultimately weaves together a moving meditation on youth, loss and growing up. It ebbs and flows like a tide –like grief — offering up touchstones as diverse as Our Lady of the Broken Toes, half-eaten Oreos, a Valentine’s Day party at a mental ward, saints and relics, paintings of sunflowers, a grease-stained bag sequestered in a purse, and the image of a girl reading a bible while working in a photo booth in the empty parking lot of a suburban mall.

That girl in the parking lot is Alison’s first love, and their scenes together do tingle and brighten each page, but the same-sex element is never overplayed. Alison is struggling through an impossible, unacceptable loss, searching for an identity that has been seemingly stolen away. While her burgeoning sexuality is nuanced and sweetly portrayed, it is always tied intricately to the memoir’s true core.

|

The book’s structure also serves to increase and sustain tension. The first section ends: “And even as my parents prayed that the Next Terrible Thing would not come, it did. ”

There is a moment about two-thirds of the way through the book when all has seemingly fallen apart and Alison is attempting to reconnect with her life. The various threads of mourning, faith, community, isolation, transgression and love all come together as a daughter watches her parents sleep. “For a small sliver of time, as I sat in Mother’s wicker rocker hugging my knees, they became my children — scared, hungry, bereft, and young, too young for all that had happened to them. ” She goes on to wonder how they are able to sleep in the face of her brother’s death, and realizes, with a heartbreaking settling of weight, how much they are depending on her.

Smith also skillfully mines the distance between church-good and church-bad. The expanse between the powder-soft comfort of an older nun’s consoling embrace and the finality of a question like “Don’t you know lesbians will burn in hell? ” is sometimes harrowing, yet this Catholic Church is also protective, giving, and kind. What is remarkable, and refreshing, is the even-handed presentation. The church is not unquestionably evil. A mother’s hard words are the result of her own pain rather than malicious intent. Mean high school girls are simply mean high school girls.

There are a number of recurring images in the novel. Some seem borne of editorial laziness (a friend of Alison’s is described, repeatedly, by a ponytail that is asked to convey far too much), while some are vital and important. These meaningful repeated images evolve throughout the novel, echoing Alison’s own process of grief. A backyard dog. An empty plate. Camping and an iconic camper van. The backyard fort. And eyes. The author always introduces us to important people through their eyes.

Name All The Animals opens with one such image – an abandoned house, sheared in half, hidden in a stand of woods. It is a potent image, made more powerful by Smith’s writing, and the simple, truthful way it is presented. Smith never plays up the melodrama. She lets her journey stand alone.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!