Making History

Thomas Mallon's 'Fellow Travelers' find gay romance in McCarthy-era Washington

As the nation’s capital or simply as an American city with infinite plots playing out at the local level, Washington, D.C., offers a great setting for stories both real and imagined. Or, in the case of Thomas Mallon’s Fellow Travelers, something in between.

Mallon, better known as a master of historical fiction than as a gay Washingtonian, has set his most recent offering in Washington of the 1950s. Amidst the long-gone D.C. streetcars and copies of the Washington Evening Star, Timothy Laughlin and Hawkins Fuller become lovers. In keeping with the genre, the affair plays out with Fuller, a dashing State Department employee, and Laughlin, a Capitol Hill rookie working for the actual Sen. Charles Potter (R-Mich., 1952-59), interacting with the events and personalities of the day — primarily Sen. Joseph McCarthy and others tied to his ”red scare” congressional committee hearings, with the Army-McCarthy hearings taking center stage. Included in the lineup is the infamous, gay red-baiter, Roy Cohn. But Fuller and Laughlin remain the stars of this story.

And the story is delivered upon very respectable credentials. Fellow Travelers marks Mallon’s seventh novel, following acclaimed works such as Henry and Clara, the tale of the couple who sat with the Lincolns on that fateful night in Ford’s Theatre. Beyond novels, Mallon has several nonfiction pieces under his belt, and contributes regularly to The Atlantic Monthly, The New Yorker and other publications.

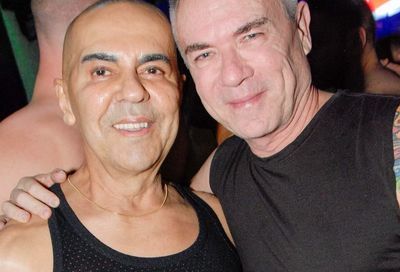

Thomas Mallon |

With Fellow Travlers the first of Mallon’s works to bring gay characters to the fore, this relatively recent addition to Washington stakes an undeniable claim to the city’s GLBT culture and community.

METRO WEEKLY: When it came time to put pen to paper for Fellow Travelers, was your primary goal to write about the ”red scare” or a gay relationship in the 1950s?

THOMAS MALLON: More than anything else, I wanted to write a love story. But I like politic — my books are full of politics and history. I wanted to write a love story about people who were under pressure — under intolerable pressure, in this case, given the time and place.

Even among friends of mine who have read the book, and with certain reviewers and so forth, some people tend to see it more as a political story, some people tend to see it more as a love story. It’s clearly both, but in my own mind it wound up becoming — if it wasn’t right from the start — more of a love story.

MW: When researching either the politics of the time or gay D.C. in the ’50s, did you come across anything that surprised you? Did any facts make you change course?

MALLON: Not so much anything that shocked or surprised me. But certain things that were confirmed to me were confirmed with such force that I had a new kind of awe.

For instance, almost all of my books have caused me to become immersed in the newspaper of the time. There have been times when I would read the Washington Evening Star for 1877 as if it was my daily paper. I was reading the Washington Evening Star from the ’50s for Fellow Travelers. It was an indispensable resource for everything — from prices to movies to the way people lived, the way they talked. This wasn’t a surprise, but if you read it day after day after day after day, at a certain point you do step back and you realize that the absolute, complete invisibility of gay people is breathtaking. It’s kind of like the dog that didn’t bark. Their complete absence from the chronicle of life is a shock. The only time you see them in the paper is an occasional vice-squad arrest, maybe a suicide. One sometimes led to the other.

Even with the Army-McCarthy hearings — Topic A in the country, being televised, everybody’s talking about it — the famous business where McCarthy and Joseph Welsh, they’re sort of gay baiting each other when McCarthy says to Welsh: ”What would a ‘pixie’ be? You just mentioned a ‘pixie.’ Did a pixie do that?” And Welsh says: ”Well, it would be close cousin of a fairy.” This was the electric exchange. If you read the papers the next day, even though people are quoting this exchange, nobody in the papers is writing about a homosexual subtext to these lines. It would’ve been too hot to even talk about. That kind of wild suppression, even if you’re aware of it intellectually, historically, it’s helpful to come up against it like that.

Sure, I learned the names of certain bars that were in D.C. at the time. [But] I would say that understanding, more than any particular fact I discovered about gay life, was revelatory reinforcement.

Fuller entered the inner office and shook hands with Mr. Traband, who immediately made it clear that there was nothing miscellaneous about the Miscellaneous M Unit. ”I’m the special agent in charge of sexual deviation investigations,” he said as matter-of-factly as if he were introducing himself as a budget analyst. ”We believe we have reason to ask you a series of questions…. Have you ever frequented a Washington, D.C., establishment called the Sand Bar in Thomas Circle? — Fellow Travelers, p. 104

MW: While doing the research, the writing, you must’ve imagined on several occasions what it might have been like for you to have been a gay man in D.C. in the 1950s.

MALLON: I’ve said on a number of occasions that historical fiction, from the writer’s point of view, is a relief from the self. I have a very quiet life, so who wants to read about it in fiction anyway? I’m not writing about the world I’m living in, generally, but you’re always present in your books on some level. But here, I was aware that even though I was writing about a past era, there was a personal dimension, clearly, with this book.

One of the first things I did when I was making notes for the character, Tim Laughlin — you fill out these false résumés for characters when you’re making notes — I put date of birth: Nov. 2, 1931. Well, I was born Nov. 2, 1951. I sort of knew at that moment that I was writing, to some extent, a book about myself as my life would’ve been if I’d been born 20 years earlier.

MW: So you relate more to young Tim Laughlin than to sophisticated Hawkins Fuller?

MALLON: Demographically. I’m not nearly as sweet as Tim. Certainly the world of that Irish Thanksgiving table was very familiar to me as a child. A quite happy, extended Irish family. This crowd is a little bit rougher in the book. I was raised as a Catholic, I was raised in a very politically conservative household. All of these figures — early Richard Nixon, the vice president; Bishop [Fulton] Sheen — I certainly remember figures like that. Not the way Tim is seeing them in his 20s, but as a boy in the late ’50s, going into the early ’60s. My parents had a background similar to the Laughlin parents.

On the other hand, as an adult, I’d seen enough of Fuller’s world. Neither of my parents had gone to college, but years later I was a graduate student at Harvard. I was lucky enough to go off to Brown as an undergraduate on financial aid. I saw something of Fuller’s tony world. But in all other respects, demographically, Laughlin was the figure I identified with.

MW: What about coming out? Did you start thinking about your sexual orientation early in life or later?

MALLON: Early. Then I sort of made my own journey through that. I think I would be described as a ”late bloomer.” The Stonewall Riot [in 1969] happened the week I graduated from high school. I remember it wasn’t that big a story. But I was aware of it. If you go back to the tabloids of the time, one of them had a headline, something like ”Queen Bees Stinging Mad.”

MW: Were you aware that it related to you?

MALLON: Absolutely, but not in any way I was going to talk about. [Laughs.] I would say my most vivid memory growing up, as an adolescent, in terms of public coverage of homosexuality, was David Suskind. He had a show in the ’50s called Open End. It eventually became The David Suskind Show. It was very serious television. He interviewed a lot of writers — he would have Gore Vidal, Truman Capote — and talk about the issues of the day. He did programs from time to time on homosexuality. I remember one time he had homosexuals come out on the program wearing hoods. As an adolescent boy who was not any kind of rebel — I was a joiner, I was built for success, a conformist — I was very aware that I was looking at myself. It was astonishment, to sit there and think, ”I’m not going to wear a hood throughout my life,” figuratively. It certainly didn’t embolden me or make me brave. I would’ve been very brave and bold, indeed, if it had. I’m talking pre-Stonewall here.

I remember years later seeing Christopher Street, one of the first gay magazines, and I can’t remember if they were wearing hoods, but it was a cartoon called, ”A homosexual interviews four David Suskinds.” [Laughs.] The implication was that if you were a homosexual, there was nothing else of any interest about you. If you had four homosexuals to talk to, there was no point in differentiating them because, you know, any individuating characteristics they had beyond being homosexual had to be trivial.

MW: Is there a moment you can point to as your coming out?

MALLON: In my generation, you were out with some people, not necessarily with others. I don’t think anybody died of shock once they knew. [Laughs.] There’s a line in the book that I put in the voice of Tim Laughlin’s sister, and it was actually from something my mother said to me when I had that discussion with her — much later than I would’ve liked to. I hesitate to say things like, ”much later than I should have.” I still think people need to do these things when they feel comfortable. But in the book, the sister, Frances, she’s on to him. She knows something is up. And she says to him, ”Anybody you care about is always welcome in my house.” The line from life that was taken from was what my mother said to me. I’ve never forgotten that. That was just about the nicest thing that could’ve been said.

It’s very difficult, too, with historical fiction. It’s easy enough to get the facts right. You can always look it up to see if a product existed at that time, or whatever. That’s easy enough. Much harder, of course, is to get the way people actually talked, the way people actually thought. I always tell people who are writing this kind of novel: Read less about the period and read more from the period. Read the newspaper, read novels, see movies from the time. That way you’ll get a more authentic sense. Eliminate the middleman. The tendency is, if you have characters you want the reader to find sympathetic, you are probably going to endow them with greater degrees of progressive sympathies when it comes to issues like race, homosexuality and so forth. And I think that this is a problem. Mary Johnson, the main female character in this book, is meant to be a very sympathetic character, trying to do the right thing in the world. But you can’t say Mary approves of homosexuality. She would certainly wish it away from both Tim and Fuller, and not just because it would make their lives easier. She is not comfortable with it. I think that it’s wrong for a reader in the present day to sort of hold that against her. You’re asking too much of a character. On the other hand, when she deals with it as a fact of Tim’s existence, what she’s angry about is that this might not be the relationship she wants to see him in, but if that’s the fact, she has a bedrock goodness that demands that [Hawkins Fuller] treat him with human kindness, with human decency.

”I suppose I don’t approve. I doubt any woman really does…. But there are things I approve of less.”

”Of our boy Skippy railing against the reds?”

”No. Of your breaking his heart.” — p. 123

MALLON: I had a heroine, Cynthia May, in a book called Two Moons]. It was very tempting to make her into a kind of feminist in 1870s Washington. I wanted to make sure she had prejudices, beliefs and so forth that did not make her a spokesperson from another world, like she’d been dropped in by spaceship from 100 years hence. In Dewey Defeats Truman, there is a main female character, Anne Macmurray. She’s kind of fought over by this Republican lawyer and Democratic union activist, almost like she’s the electorate, set in ’48. When my mother read that book, and she was a young woman in the ’40s, she said to me, ”You know, I think your heroine is a little fast.” [Laughs.] I had to remind myself of what the word meant. Contrary to my mother’s beliefs, I don’t think premarital sex was invented around 1995, but she was going to the heart of the matter: Are your characters behaving in a way that’s plausible, or are they behaving the way we behave today?

Advertisement

|

MW: For the gay D.C. in the ’50s research, you point to David K. Johnson’s The Lavender Scare in your acknowledgements. Where else did you look?

MALLON: One book, which is just god-awful, but stocked with details, is Washington Confidential by Jack Lait and Lee Mortimer. It’s written in this hysterical, tabloid language. It’s ferociously anti-gay — it’s all ”pansies.” There is a chapter about gay Washington, and it does have specific locales and names of bars, things like that. But it’s a very tainted source. [Laughs.] I had to go to this sleazy book to get some nuggets. I would strongly recommend David Johnson’s book, The Lavender Scare, for the real history of what went on, particularly in the State Department. It’s very well researched and well presented.

The funny thing is, while Fuller goes out to gay bars and I think Laughlin steps in one once, the romance they have is so clandestine. I didn’t want to give much of a picture of gay life in Washington, because they weren’t living it. One of the things you can glean from books like The Lavender Scare is that there was more gay life and community than people might think. But I wanted this romance to be very, very claustrophobic. It takes place entirely in Fuller’s apartment on I Street and Laughlin’s illegal apartment on Capitol Hill. A book about the texture of gay life in D.C. is another novel. This was a compressed, clandestine romance.

MW: A spin-off of Hawkins Fuller’s trysts would make a great beach read.

MALLON: What’s interesting to me is that some people are going to think of Fuller as this terrible character, who makes this poor little boy so miserable. God knows he has his flaws, but he’s a victim too. He has a whole different set of resources from the ones Laughlin has to cope. He has his spectacular looks, he’s got more money, he has a fancier education and so forth. But he’s doing all these things like getting married, because he’s not really able to live his life by himself. Certainly he’s an emotional catastrophe in a lot of respects. I hope, on the surface, I made him an attractive character. I don’t think of him as a bad guy. Part of the book is about how ”half requited” love is harder than fully unrequited love. He’s definitely fond of Tim. I think he’s afraid of the extent to which he’s fond of him. He’s so self-protective by nature, where Tim is a heart-on-his-sleeve kind of guy. Fuller knows how to make it hard on him.

MW: In spots, it gets a little racy.

MALLON: I’m astonished to discover the number of reviews that refer to the ”surprisingly graphic sex scenes.” I’m thrilled to see this. [Laughs.] There are a few torrid moments in Henry and Clara, actually, right in the old, prim 19th century. If you took the same amount of sexual depiction, if the two characters were heterosexual, I don’t think anyone would notice it. It’s certainly not a large part of the book. The sex scenes in the book I think are absolutely crucial. I sound sort of like a starlet on a talk-show couch: ”I would do a nude scene only if it were integral to the plot.” [Laughs.] I don’t think there’s any reason sex can’t be gratuitous in serious fiction. Sex is an interesting part of life. In the scenes where the two of them are having sex, I think you learn more about them and about their psychological relationship than you do at any other time in the book. They’re sort of naked in more ways than one. All of those scenes are meant to really advance the reader’s understanding of them, psychologically.

MW: While you were writing Fellow Travelers, did you ever visit any of the important settings for inspiration?

MALLON: One thing that appeals to me about Washington is there is so much of Washington that can’t be torn down. By its very nature, it’s a city full of landmarks. The geography is very unchanging. It’s very easy to walk down a street and imagine yourself back 50 years. There is a scene between the two of them in the Old Post Office tower, and I worked in the Old Post Office when I worked [for the] National Endowment for the Humanities. It did strike me as an interesting trysting place. I did wander around Capitol Hill and look at the places where McCarthy lived.

”Two more blocks,” Hawk said, pointing to the Old Post Office, their destination, a gigantic Romanesque pile between Eleventh and Twelfth streets. Once there, Hawkins took them around the back to an unlocked door: ”Tip from an FBI friend,” he explained. — p. 216

MALLON: I mention the almost complete absence of gay people from something like the Washington Evening Star, but in terms of life among the heterosexual and politically famous in Washington, there is a wealth of material. There is no other word but ”fabulous!” All the cultural clichés of the ’50s, the Ozzie and Harriet clichés, fall away very fast when you are looking at political and social life in Washington at the time. It’s a really flashy, outsized era. Big personalities. Big misbehavior. Big drinking. Big oratory. Despite Ike and Mamie, it’s not gray; it’s very Day-Glo. It didn’t come as a complete surprise, but in thinking about it and seeing it unfold day-to-day in something like the Evening Star, you’re impressed by the flash of it.

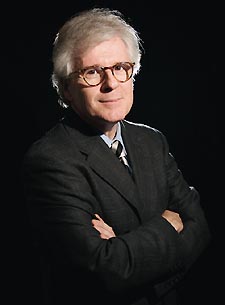

MW: And what was your impression of the book-jacket photo? It seems perfect for your story.

MALLON: I found it. I’m quite proud of that. It’s a Weegee [Arthur Fellig] photograph. He was a photographer for the tabloids. He has almost no association with Washington, D.C. That photo was taken in New York. Weegee photographed a lot of crime, a lot of tabloid lowlife in the ’30s and ’40s. I had a book of his photographs that I was looking through one evening, maybe a year ago, and I saw a series of photos he took relatively late in his career, in the mid ’50s, at a Greenwich Village bar. Not a gay bar, either. I’m almost dead certain that the fellows in the picture are not gay, because I’ve seen the other pictures in the series. But there’s something about this shot, they way one is looking at the other, how the younger one is looking up. There’s something so openhearted about that boy, that face. I looked at this picture and I gasped and thought, ”This could almost be the two of them.”

I kept the picture in mind when I saw the first cover of the book. The art director, I hasten to add, is excellent and has really done me proud with a number of covers. But the first cover I saw was an old black-and-white photograph of McCarthy with these sort of high-styled ’50s magazine illustrations of two couples at nightclub tables, a man and a woman in each case. It was very evocative of the ’50s, but I sent my editor an e-mail saying, ”Isn’t this a little like putting Dale Evans and Roy Rogers on the cover of Brokeback Mountain?”

MW: Will you revisit gay themes in future novels?

MALLON: I’m torn between two different novel ideas at the moment. One of them is a gay story that takes place mostly in New York from about 1950 to 1980. The other is a book set in New Orleans in the 1930s. It wouldn’t be a gay story per se. Maybe I’ll write both of them. [Laughs.]

I should live so long.

Thomas Mallon reads from Fellow Travelers Thursday, May 17, 7 p.m., at Chapter’s Bookstore, 445 11th St. NW; and Sunday, July 1, 1 p.m., at Politics and Prose Bookstore, 5015 Connecticut Ave. NW.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!