Tina Romero is Queering Up Zombie Movies

The filmmaker blends bold queer storytelling with the horror legacy her father built, creating a zombie film that’s entirely her own.

“I hope to one day make a movie musical,” says Tina Romero. “I would love to do a fantasy piece. I am trying to put all the pots on the burner and see which one I can get to boil. Because it’s a miracle to make a movie, and it’s a miracle to get all the pieces in place. But I am salivating to make another one.”

For now, the LGBTQ world — and beyond — is salivating to see Romero’s debut effort, Queens of the Dead, a vibrant, unapologetically queer take on the zombie genre her late father turned into a horror institution.

Made in 1968, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead remains a truly terrifying game-changer in horror. It’s the film all others bow down to, replete with classic lines (“They’re coming to get you, Barbara”) and gruesome depictions of zombies feeding on human viscera. Both Night and its 1978 follow-up, Dawn of the Dead, formed the first two parts of a trilogy that spawned dozens of imitators, remakes, and even a second trilogy from George himself.

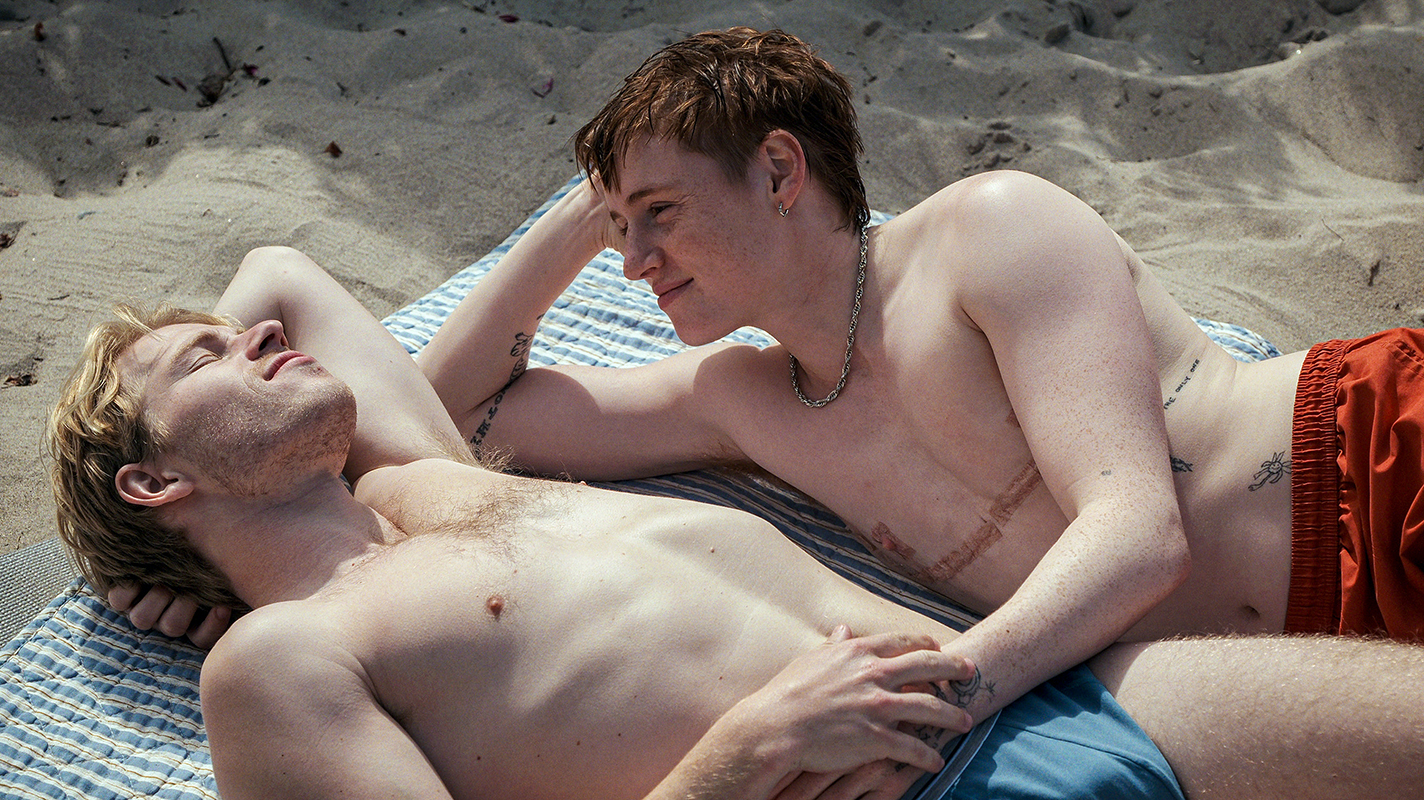

Queens of the Dead feels familiar, fresh, and yes, familial — overflowing with the queerest cast this side of Bros. The ensemble includes Katy O’Brian (Love Lies Bleeding), Jaquel Spivey (Mean Girls), Jack Haven (I Saw the TV Glow), Eve Lindley (National Anthem), Dominique Jackson (Pose), Margaret Cho, Broadway superstar Cheyenne Jackson, and the irrepressible Nina West. Tina Romero artfully blends comedy, camp, and chills for a perfectly balanced mix. (Just wait until you see the Sugarwood Penis Waffle scene.)

The zombies are glittery and gross-glam, partly by design and partly by necessity.

“We couldn’t afford to do contact lenses and we couldn’t afford to do VFX on their eyeballs in post-production,” says Romero on a recent Zoom chat from her New York home. “But I am totally fine with that. I like that we can see their human eyes. I think it adds a layer of humanity to the zombies.”

Otherwise, she sticks to the zombie rules defined by her father. “They are slow, they’re sympathetic, and they’re silly,” she says. “And yes, they’re scary en masse. A zombie mob is terrifying. But one or two of them? Not so much of a problem.”

“Making the film was just so special and fun. It hit right at the heart of the queer community and in this world that she has such a legacy attachment to,” says O’Brian, who’s no stranger to the zombie genre, having appeared in the TV shows The Walking Dead and Z Nation. “I love that she wanted to take her dad’s genre but really put her own twist on it. When I read the script, I was like, ‘Oh man, I have to do it. I have to do another zombie project.’”

O’Brian plays the tough, somewhat beleaguered owner of a floundering nightclub who must rally her fellow queers in a fight for survival against legions of dead, brain-starved club kids.

“Tina wasn’t like, ‘Oh, we have to check these boxes for this type of representation,’” says O’Brian. “I think when you have writers who are queer, you already get that authentic kind of representation. Sometimes [writers and directors] are like, ‘Oh, we have to insert lesbian here,’ and they just don’t quite get how we want to be represented or why we want to be represented. But Tina just got it.”

The 23-day shoot took place in an inhospitable Paterson, New Jersey, warehouse with broken air conditioning during a July heatwave.

“Everybody just brought their A-game,” marvels Romero. “Nobody was complaining. We had two drag queens in heels and wigs and padding in the heat, and not a grumble. We didn’t have the money to house people, and most of our crew is from Brooklyn, so we were all commuting an hour and a half there and back every day. I think on some level, if you’re going to make a low-budget zombie film, it should be sort of a shit show.”

For Romero, the film isn’t just a tribute to her father, but is also an allegory for how today’s LGBTQ community must band together to fight a hostile administration.

“I’m happy that this film is coming out now in 2025,” she says. “It has a more uplifting spirit — like here we are, we’re fabulous and we’re fun, and we are survivors. It feels like a good type of queer film to put out right now against the bleak violence against queers. That is what’s going on outside. So Queens of the Dead is a bit of an antidote to that.”

METRO WEEKLY: You’re a Romero, you come from zombie blood, so to speak. What was it like growing up George Romero’s daughter?

ROMERO: Oh, man. My dad was my hero, my idol. I loved him so much. He made some really dark and twisted movies, but he was such a gentle giant. He was such a big muppet — silly, joking, loved Disney, loved movie musicals.

Our primary form of bonding was always doing a project. He was a big project guy, and maybe that was his way of unwinding, but he would immerse himself in. If I had a desire to put on a little cheesy show for my parents to the soundtrack of the Disney Afternoon — because I was also a Disney kid — he would help me make props for it. He was a really incredible artist.

So when he was present, he was really present. And then he was away a lot. He was working a lot, and I sort of had to learn how to give him the space and let him do his thing.

I describe myself as an edgy cheeseball — I grew up on all the cheesy stuff, Pippi Longstocking, West Side Story, Bye Bye Birdie. But then I would walk to the bathroom at night past terrifying movie posters, like the Monkey Shines movie poster — it was so scary — and the Martin “blood drip off the razor” poster. And there was Fluffy’s crate [from Creepshow] in his office with chains and fake blood. I was not convinced that Fluffy wasn’t in there. So I always walked by his office a little faster. I feel like there was just this weird mashup of dark and light, which is, I think, at the core of my creative spirit. I like things light and fluffy and pink — but also I love a drop of gore.

MW: Your father’s legacy helped re-form the horror industry, and that’s not an understatement. He didn’t go out and say, “I’m going to change horror.” He just did.

ROMERO: Yeah, he was an incredible mind and incredible student of cinema. He loved old classic cinema. The two channels on in our house were always Turner Classic Movies or CNN. He was very politically minded — he was cursing at the TV all the time, cursing at the news, but then he would escape into the classics of film. And he really wanted me to be a student of cinema alongside him. He would take it very seriously if you were going to sit down and watch a movie. He did not want any interruptions, no phones. It was all in. And he would look to me and see how I was reacting.

One of the things that impacted me greatly was that he was also unabashedly open about being moved. He would weep in front of me as the opening notes of the West Side Story overture — he would just cry and let himself feel how much that moved him. And I think witnessing him be so openly moved by film showed me the power of how film can provoke real-life empathy.

Maybe that was a safe space for him to show his emotions. He wasn’t the most emotionally connected dad in other ways, but in the space of movies, he would go there. And I think that that’s why his films are special. He’s doing horror, but he’s also coming from a place of really loving the classic old movies.

MW: Do you have a favorite classic from your time with him?

ROMERO: West Side Story, I would say. I mean, I love musicals. He did, too. And I love dance on camera. I think that one really is perfect.

MW: You know, I remember that Monkey Shines poster. That is not a happy poster.

ROMERO: [Laughs.] No, it’s really creepy! My dad was an avid collector and had all this horror stuff in his office. He had some dark shit. There was one book in particular — a werewolf book. It was like an encyclopedia of werewolves that just captivated me. It scared me and I was drawn to it at the same time, and I would just obsess over these images of werewolves. And then, I would have night terrors about wolves. It’s that weird thing about scary stuff where you’re drawn to it even though it triggers this bodily fear.

MW: Well, I’ll tell you, I would be hesitant to walk into any room with Fluffy’s crate in it.

ROMERO: Yeah, it was terrifying. That was the scariest thing in our house. It was chained up and I just had a little voice in my head that was like, “He could be in there.”

MW: At what age did he finally let you watch his movies?

ROMERO: I get asked that sometimes, and my true answer is I don’t even remember. There wasn’t a moment of like, “Okay, you’re allowed to watch them now.” They just always were there. There was no censorship. I saw Close Encounters of the Third Kind before the age of five. I saw Jaws before the age of five. If it was on, I was watching it with him. We just watched shit. And so I feel like the films came to me when they came to me. When I got into my teens and started to form my own brain, I remember seeing Knight Riders for the first time as a thinking person. I remember seeing Creepshow as my own person, and I remember waking up to his films and thinking like, “Oh wow, these are great movies.” Even though I had seen them in my youth, it wasn’t until I formed thoughts as an adult that I started to really appreciate them. Creepshow is one of my favorites, for sure. I think the colorful lighting, the poppy colors, the short format, the anthology nature. I love Creepshow.

Monkey Shines, I like a lot. I have a hard time watching it because my mom [Christine Forrest] plays the Nurse Ratched character, and when her bird dies, it just guts me. Her reaction did a number on me when I saw it young. And so, I kind of put that movie over here, because it’s too hard to watch that. I love, love, love Dawn of the Dead. I love Survival of the Dead because I feel like it’s the most production design my dad ever got with a film. Have you seen that one?

MW: I have not.

ROMERO: It’s not one of the most popular, but I like it a lot. It was his opportunity to do a Western aesthetic. He loved the Westerns. He loved, loved, loved John Wayne. And this one, he’s got the two feuding families. Even the final shot is two zombies over a hilltop silhouetted having a showdown. I feel like he got to express this part of himself. It has a different vibe from a lot of his other work.

Diary of a Dead is not one of my favorites. But I also associate that with kind of a dark time in my family history. My dad left the Pittsburgh life and my mother and moved to Toronto. And I refused to let him go. I very much stayed in his life. Diary of the Dead marks that transition time. So I associate that film with an icky part of our family history. Sorry, I got off on a tangent.

MW: It’s fine. Tangents are welcome. You have a different association with his movies than most people. I remember when I first saw The Night of the Living Dead, I was in college, and it scared the hell out of me. I’d never seen anything like it. I’ve watched it recently within the last few years and the scene where the mother is killed by her daughter is shocking. I can’t even describe the dread of that scene.

ROMERO: He’s introducing this monster and is really hammering home the point that when it comes to the zombie apocalypse, it can turn anybody. It could be your family, it could be your best friend, it could be your neighbor, it could be your cousin, it could be your kid — and they’re not your kid anymore. They are out for brains, out to eat you. My dad would say that the zombie is the most blue-collar democratic monster. Unlike a vampire, where they’re choosing you, anybody can turn into a zombie at any point. No one is safe.

MW: On a personal note, when did you come out to him?

ROMERO: In college. I sort of tested the waters with my parents. I first got my nose pierced and I called them to tell them I got my nose pierced as a way to see how they would react. They were both on the phone, and my mom screamed and dropped the phone, and my dad laughed and was very cool. When I came out, both of them were very cool. Well, my mom was maybe a little bit — she opened the wine and took a sip and was like, “Was it Wellesley?”

My dad’s reaction was very much like, “You know what? Guys are asshole anyway. Great.” And shortly after that, he booked tickets in Pittsburgh to go see Margaret Cho’s comedy tour. And he also, that same year, got tickets for us to see a stage production of Hedwig and the Angry Inch that was on tour. With both events, I feel like he was saying like, “Look, I’m cool with you kid. I see who you are and it’s okay.”

MW: Dads can surprise you. When did you realize for yourself that —

ROMERO: I liked girls? It was college. My second year of college I was an R.A. and I had to go early to lead these diversity talks ahead of time. And there was a girl in one of my groups that I just felt feelings for. It was very organic. It just hit me out of the blue. I couldn’t deny it. I was like, “I have a crush on a girl.” And I was lucky enough to have some really good friends left over from high school and I processed it with them. They were all like, “Go for it, follow it.” And it was thrilling.

I remember how amazing it felt to come into my skin in that way, and just to realize, “Oh, this is what I’ve been missing in my life. This is what real connection feels like.

I went to Wellesley for the academics — I did not go there knowing that it was a paradise for women who love women. And then I found myself there, and I was like, “Oh, amazing.” What a perfect place to discover your sexuality. And then very shortly after that I saw But I’m a Cheerleader — that movie rocked my socks off, and then it was on. I feel like I had my renaissance as a human.

MW: So your mom was right. It was Wellesley.

ROMERO: [Laughs.] Maybe it was Wellesley. It wasn’t like I didn’t know about gay stuff, but there weren’t a lot of lesbians in my high school. And so it wasn’t really on my radar as a way to be, if that makes sense. But again, it wasn’t because I was around queerness that I came out. It was because I met someone who sparked emotions in me, which felt really natural and organic.

And then, cut to my senior year of college. My dad was making Land of the Dead, and I went to Toronto to do a part in the movie. I play a soldier. It’s actually a very embarrassing shot, because I’m not a great actress, and I am dressed in fatigues and I’m holding a BB gun. I think my line was, “Stench, 10 o’clock,” and my dad was like, “I want to do an homage to John Wayne and say ‘Stench, high noon,’ instead.” And I thought it was so cheesy, I don’t know why. So you can see me cracking up. I say “Stench, high noon.” And my boss goes, “Take his face off.” And then I shoot the gun, and I just crack up. I think it’s a terrible performance, but I’m in there and my girlfriend at the time came with me, and they got her all zombied out, and I was so tickled walking around the set as a gay zombie soldier couple.

MW: Let’s move to your film, Queens of the Dead. It feels like you are paying tribute to your family legacy, just in a very queer way. Am I wrong?

ROMERO: No, you’re not wrong at all. It is a big old gay movie. But my hope is that it’s not alienatingly queer. I really hope that everyone feels invited to the party.

MW: It feels that way. I remember thinking while I was watching the first time, it isn’t just a horror show, it isn’t just a comedy. You start to get real feelings for these people. You get real emotion in there as their situations, without spoiling it for people, play out. You’ve layered it with a lot of heart.

ROMERO: I wanted to play with the tropes of the zombie film. And so much of a survival movie is about your survival crew. I really wanted to flip the script. Instead of having the token gay and the crew, I wanted to have an entire queer motley crew with the one straight guy from Staten Island.

Erin Judge, my co-writer, and I have done a few shorts and I love working with her. She’s hilarious. She’s a stand-up comedian, and a novelist, and a total brain. And I knew she was the perfect collaborator for me on this one because she’s so good at getting character through dialogue. And that’s hard to do because it can feel expository, but she knows how to get a character across through the words that they’re saying.

We’ve been working on this for eight or nine years, and I think by nature of time being in it for so long, we had backstories for every single character. And over the years, we just whittled it down to the essentials. And so I think what was on the page worked pretty well already. And then when you bring in this cast — this absolute dream cast — all of whom are so interesting and dynamic and funny, and they bring these words to life, they bring a whole other layer to it.

Kelsey, for example, could have been a boring character, but Jack Haven was able to go kind of weird with Kelsey. They said they wanted to channel Barbara from Night of the Living Dead, but also give a little bit of their Russian drag queen alter ego.

Jack Haven, by the way, was a last-minute get. The person who was supposed to play Kelsey was no longer available. And I was a fan, a huge fan. I loved that show Atypical. I Saw the TV Glow — [Jack] was on my radar, but I was like, I really want Kelsey to be high femme and I’m not sure that Jack is going to be down for that because their gender journey is not a feminine one.

I said, “Are you down for this? I really want Kelsey in a mini skirt. Are you down to shave your legs?” And they were like, “Yes, I love playing a girl. I have an alter ego that wears a blonde wig and is a Russian drag queen, and I will channel her.”

MW: I’m glad that you don’t slaughter everybody. This is going to sound horrible, but you kill judiciously. You are very careful about who goes — and how they go.

ROMERO: Writing it, Erin and I really didn’t want to kill our people. It’s hard to. And also, by the way, a really large bulk of our writing got done during COVID. Everything was shut down. We had more time, we got a lot of drafting done, we had drafts, but we pushed it home during COVID. And at that time, we were like, we don’t want to see something dark and depressing — we want to be uplifted. And also, we’re telling this survival story of the community. We didn’t want it to be a “Final Girl” movie. We wanted most of them to get out alive. We wanted the spirit to be that the community sticks together and makes it out. We knew we had to kill some, but we didn’t want to kill all.

So, yes, we were judicious — I like that word — about who we killed and when. I always knew that I wanted the hot white guy to go first. Jimmy, poor Jimmy — Cheyenne Jackson. I mean, as much as I’d love to have Cheyenne on camera this entire film, it was our intent to kill him off first. We knew that we were going to have to take Jimmy out. And it’s sad, but it’s meaningful.

MW: I do have a question about Jimmy, though. He’s bitten and dies and I thought for sure he was going to come back as a zombie. Is there a scene lying about somewhere on the cutting room floor?

ROMERO: I wish. We didn’t have time. I really wanted Jimmy to get out of the cooler and sit up in the dress bag. It’s begging for it. But we were out of time and out of money. I actually feel like we’re lacking two resolutions — Jax [Samora la Perdida] in the go-go cage and Jimmy in the cooler. We just ran out of time and money.

It was a hard shoot, and I can’t even believe we pulled it off. I think that the reason that we did pull it off is because we had the fighting spirit of the gays. This was a 98 percent queer crew. On camera, it’s a story of communities surviving something crazy. Same story behind the scenes as well. We were just all determined. I can’t even believe how lucky I got with this crew, but every single person just did the most to make it happen.

We had a two-person hair department — we had so much hair going on in this movie — and Mitch Beck was able to pull off all of these wigs with his right-hand, Monique. It is just phenomenal what they were able to do. Same with David Tabbert, head of costumes. I just can’t believe the blood, sweat, and tears that everyone put into this film. It’s truly remarkable. We got a lot for what little we had.

MW: The production values are tremendous. Really slick. Obviously, you pay tribute to your dad in it. But one of the things I loved was how it calls back Dawn of the Dead, where the zombies all go to the shopping mall as they did in life. Here they’re all still glued to their phones, going to the club, as in life.

ROMERO: I very intentionally wanted to call back Dawn of the Dead. I had to keep the zombie mythology. Traditional Romero — they’re slow. One bite turns. You got to take out the brain to take out the monster. And then, I wanted to add that they’re still responding to their devices, which I think my dad would have approved of, because we are. We have streets full of phone zombies out here. It’s wild. And I’m freaked out by it. I’m freaked out personally how much this phone has changed my own brain in the past decade. I think the biggest enemy in the film is big tech, that’s the thing that’s really driving us to devour ourselves. It’s devouring our brains, the tech.

These zombies, they’re freshly bitten on a Saturday night in Bushwick. They’re not wearing their denim and their flannels. They’re out on Saturday night, and they’re going out to the club. And I wanted them to have personality just like the zombies in Dawn of the Dead. I wanted there to be fun personality and some sequins.

MW: As a filmmaker, do you think it’s harder to scare people or to make them laugh?

ROMERO: Oh, my God, that’s a great question. I think it might be harder to make them laugh because you can’t force it. It’s hard to force a joke. You can kind of force a scare. But they are similar. It’s both a set up and a punchline. They’re two sides of the same coin.

But there’s something with trying to make people laugh — you can feel when someone’s trying to do it, more than you can feel when someone’s trying to scare you. With scares you bring in the music, you bring in the sound effects. But you don’t have all those tools when you’re trying to make someone laugh necessarily. So comedy is, I think, a little bit harder.

MW: And finally, what scares you?

ROMERO: Sharks. What’s lurking in the water? I have the spirit of a surfer, I really identify, as I want to be Moana. I want to run into the water. And the second I get to the edge, I’m running right back out, because I’m so certain that there’s something that’s going to eat me. Bathtubs, deep ends of swimming pools, there is a monster lurking in the water at all times for me, and I hate it, but it’s my most visceral fear. Getting in the water, it’s like my heart rate increases. I can’t breathe. I just want to be frolicking in the waves, but I am so deeply terrified of Jaws.

But, actually, I am desperate to make a shark movie. My favorite genre. I love chompers. I love them. I love them. I love them. Jurassic Park, Anaconda, Cocaine Bear. That’s my Friday night popcorn movie choice. I want to see people getting absolutely devoured by animals. I love it. And so Erin Judge and I, the next thing that we’re writing — we just started — we’re going to write our queer Jaws.

Queens of the Dead is rated R and is playing in theaters nationwide, with streaming availability in the near future. Visit fandango.com.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.