DC Theater Review: ‘Everybody’ at Shakespeare Theatre

"Everybody" puts amusing, compelling thought at the mercy of randomized casting

Cerebral and puckishly subversive, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is the kind of playwright who is in fervent discussion — not just with his audience, but with himself. He wants to think out loud and he really wants company.

Be it race, family, or the human condition, Jacobs-Jenkins is turning over ideas, lifting conceptual rocks, and usually employing an entertaining narrative while he’s at it. But — and it’s a crucial but — he also assumes a savvy audience; people who are up for an unfettered but always artful examination, those who won’t be rocked by an unsettling challenge provided that it’s delivered with warmth, intelligence, and humor. Put simply, Jacobs-Jenkins is a thinking person’s playwright.

With his adaptation Everybody (★★★☆☆), he turns his attention to a 15th-century morality play called Everyman, a medieval reminder that, grand or humble, we will one day meet the greatest leveler of all: death. In his reimagining, Jacobs-Jenkins takes this premise and runs it through a 21st-century filter — in all its neurotic, agnostic glory — delivering an updated death angst and ironic eye on all we do as we scrabble to shield ourselves from our last inexorable moment.

In Jacobs-Jenkins’ hands, as the protagonist named Everybody gradually comes to the realization that death is nigh, it is not just clever in its dream-within-a-dream format, it’s often amusing. It is therefore all the more disarming when the home truths begin to emerge. And though we may not wholly relate to this particular protagonist, the point is we don’t need to. Regardless of whether we would have them over for dinner, when it comes to the exit door, we are they and they are us. And so, in the least preachy way possible, Jacobs-Jenkins suggests we consider, if not tenderness towards our fellow humans, then at least forbearance.

Always theatrically mischievous, Jacobs-Jenkins doubles-down on his theme that we are anything but exempt from the message by flagrantly, joyously breaching the fourth wall. Indeed, it isn’t so much breaching as pushing that wall out beyond the sitting audience. It’s worth noting — especially in light of Woolly’s recent Fairview, in which audiences were expected to take the stage — that Jacobs-Jenkins lets his players do the breaching. It may be less provocative, but if you want people’s brains to function, you probably shouldn’t traumatize them.

It’s no secret that one of the other devices here is the use of a live lottery, in which five of the actors find out on the night of any given performance who of five characters they will play. Another reference to the “your number is up” aspect of death, it is also, without a doubt, something of a theatrical stunt obviously intended to delight the audience. But, truth be told, here is where concept must meet execution, and not just with respect to the challenges of a lottery performance, but simply in managing the entirety of Jacobs-Jenkins’ wild imagination. Although parts work wonderfully, the whole never fully gels.

As a witty Usher, Yonatan Gebeyehu might capture the right voice in wittily chiding the audience, but his later reappearances feel uneven. Similarly, the choice to make his God snarky, as opposed to something subtler and perhaps genuinely sinister, diminishes the presence (as does the Usher’s awkward transformations). If this was intentional, it wasn’t clear, and that’s a problem. This is where director Will Davis needed to anchor the vision.

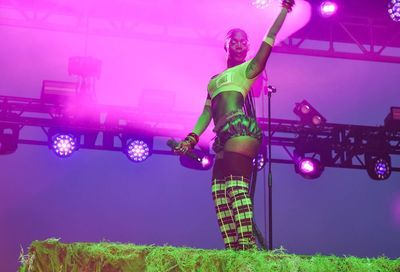

But the real hazard is the challenge of the lottery. If there isn’t enough pre-production preparation, the actors may be lauded as brave, but the play won’t be well served. Case in point was the performance of Avi Roque, who took on the role of the protagonist, Everybody, on press night. Roque brings energy, but little nuance and the almost exaggerated feel of the characterization clashes with the play’s increasingly introspective monologuing. Playing it large may showcase Roque’s charisma, but it misses a connection with the material.

And there was scope for a lot more had this been a compelling protagonist. The play’s final sequence, when personification takes over as Everybody nears death, is clever and even appropriately gloomy. But as potent the ideas, without a convincing protagonist, it never stirs the innards.

This disconnect appears again in the smaller role of Everybody’s cousin, where Alina Collins Maldonado never quite catches Jacobs-Jenkins’ ironic wave. And as another cousin, although Ayana Workman infuses the necessary irony, she seems too tamped down for this largely-writ production. One of the better performances, if a tad tentative, is Kelli Simpkins as the Somebody representing material possessions and money. Playing to the crowd, she makes the most of a clever concept. Strongest of all is Elan Zafir who plays Everybody’s fair-weather friend. Zafir has fun with Jacobs-Jenkins’ rapid-fire patter and “dude” persona, bringing some of the verve and genuine laughs the piece deserves, even if it is impossible to see the chemistry these two supposedly have. In the end, these lottery performances are too mixed a bag and, as good as they all are under the circumstances, the unevenness distracts.

In the non-lottery role of Death, Nancy Robinette feels ever-so-slightly miscast, but she obviously delights in the concept and chooses some exceptional phrasing in her delivery. Her statuesque presence at the end, replete with translucent raincoat, is memorable. Another standout is Ahmad Kamal as Love, who, by playing it with utter, understated conviction, brings some of the only pathos of the evening.

However, even if this production may never quite sing (and different nights will see different configurations), an evening in the room with Jacobs-Jenkins is always worthwhile. To experience one of his plays is to feel him pacing the aisles, checking our reactions against his own. When he lobs his challenges, it’s not to chide or be teachable, but to ask, “So what do you think of this? And now, what do you think of what you think?” And it feels like he really wants to know.

Everybody runs through Nov. 17 at the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Lansburgh Theatre, 450 7th Street NW. Tickets are $49 to $120. Call 202-547-1122 or visit www.shakespearetheatre.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.