Putting It Together

Witeck-Combs Turns Ten

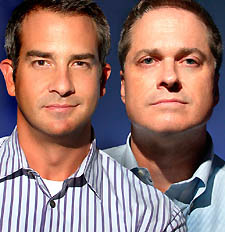

Photography by Todd Franson

It’s not easy finding the perfect job.

Bob Witeck spent the first ten years of his professional life working on the Senate side of Capitol Hill as a press secretary. Another ten years went by at public relations giant Hill & Knowlton before he struck out on his own as an independent consultant. Still, it wasn’t quite what he was looking for.

Wesley Combs went straight from studying marketing and business at Georgetown to working in sales and marketing for IBM. Over his years on the young executive track, he found he had more passion as a volunteer than as an employee.

Then, in the early fall of 1993, the two of them had an idea of how to bring together their experience with communications and marketing with their passion for issues and causes that make their community stronger. Witeck-Combs Communications was born.

“The things that inspire us are building up the values of our community,” says Witeck, 51. “It’s saying things about gay people in all aspects of our lives, in the marketplace, in public policy, and in the community.”

While that focus on the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (GLBT) community is one of the core aspects of their business, their partnership includes work on a broad ranges of issues and clients. In addition to their work with such groups as Food & Friends and the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), they focus their efforts on organizations ranging from the Christopher Reeve Paralysis Foundation to the newly opened Washington City Museum. And they’ve worked on diversity issues and GLBT marketing strategies for corporations ranging from American Airlines and Wachovia to Ford and Coors Brewing.

|

“I think we draw upon our commitment and our passion to our community, and we apply it to many other areas,” says Combs, 40, of the breadth of their focus.

Now celebrating its tenth anniversary, Witeck-Combs has carved out a name for itself in a city teeming with communications and public relations firms and professionals. Their research into gay and lesbian demographics earned them a spot in American Demographics magazine’s recent compilation of consumer trend experts. And Combs just received the 2003 Trailblazer Award from Out & Equal for their work on workplace diversity and equality issues.

A lot can happen in ten years — even the perfect job.

METRO WEEKLY: How did you first get into public relations and communications?

BOB WITECK: When I got out of college I ended up working on Capitol Hill. My dad had worked there for most of his career, starting in the 1950s. So we’ve had two generations working up there. Though I’m a lifelong Democrat, I worked for a Republican senator as a press secretary for about a decade. I learned media relations by working on issues and public policy. One of the things that I most remember was Lou Chibbaro [of the Washington Blade] calling me up on stories. This is in the late seventies, which tells you how long Lou’s been around. It was a time when things were beginning to ferment in terms of public policy and gay issues.

I was challenged early on to write speeches and news releases and that became the thing I most loved. It was the thing my boss wanted me to do, and it’s why I became a press secretary almost right away. I learned journalism from the other side, where you learn two things very quickly. One is that writing is the core of what we do, which I love. The other is, we have to know what journalists do. And I think the trust in the relationship you evolve with a journalist is based on understanding their responsibilities.

WESLEY COMBS: I was a marketing major in college. I graduated and went to work for IBM in marketing and sales for about eight years. I got a great career foundation, but I wasn’t fulfilled in what I was doing. I spent a lot of time volunteering in the evenings for non-profits, mostly the Human Rights Campaign. I found I enjoyed working there more than I did during the day. So I ended up leaving IBM to work at a consulting firm, but I still wasn’t happy.

This is where our stories converge. I’m not speaking for Bob, but this story’s pretty much the same when we both tell it.

WITECK: [Laughs] We’ve got our alibis together.

COMBS: At that time I was on the board of HRC and I was attending a board meeting in Dallas. Bob had just left Hill & Knowlton to go off on his own, and was there because the HRC foundation was one of his first clients. We knew each other through our work with HRC, so we were sharing a hotel room that weekend. He wasn’t that happy being off on his own — he said he wanted to collaborate with somebody or a small group of people, but he didn’t want to go back to a large firm.

The board was reviewing the merger of National Coming Out Day into HRC. I said to Bob, I would love to work on that project, I know what that project needs — it needs to have visibility, it needs celebrities, it needs public service announcements. I said to Bob, why don’t I work on this on a consulting basis for the foundation. Then you’ll have somebody to collaborate with and we’ll start a business. He said it sounded great. [Laughs.] Then it took two weeks to convince me that what I said was something I felt comfortable doing. And so October 15, 1993 was the day our little certification of occupancy from the District government says is the founding of Witeck-Combs in the basement of my townhouse.

MW: When you first went into the business, did you assign yourself roles for what you wanted to do in the partnership?

COMBS: The structure and setting up the business fell more to me because it was stuff I had studied. Actually, as our firm has progressed, I’ve pretty much been more involved with the day-to-day running of the business. Bob started out doing more of the media relations tasks, and I did more of the marketing projects, because those were our backgrounds when we started. From my standpoint, I learned pretty much everything I know about media relations from Bob.

WITECK: And that’s the same for me, because everything I know I’ve learned from Wes in terms of his professional skills. He understands business far better than I do, and has given me a great luxury in knowing that somebody smart and capable has that grasp and his patience to do it.

MW: Bob, you said earlier that you learned about journalism from the other side. What’s the most counterintuitive thing you learned about journalism? What most surprised you?

WITECK: Actually, nothing. What I needed to know then was the thing I use today, thirty years later: the knowledge that they are fellow professionals. People mythologize journalists. People have a great fear of journalism for a lot of reasons. They don’t understand that journalists are not your friends or your enemies. Journalists have the tyranny of deadlines, the tyranny of space. They have to take complex ideas and translate them into something their readers want to know about. [Our job] is making people feel comfortable working with the press — that it helps your business, it advances your mission.

Our work is values based. We feel that if you’re going to be in public relations and marketing, you want to work on things that inspire you. And the things that inspire us are building up the values of our community, communicating about gay people in all aspects of our lives: in the marketplace, in public policy, in the community. It’s taking the story about who gay people are and making it understandable. It’s important that we bridge to larger communities and we put our community in context accurately. Being able to work with journalists, both straight and gay, who may or may not have an understanding of the full depth of who gay people are, is invaluable. So you have to work with them as professionals.

COMBS: Coming from a corporate perspective, I worked for IBM at a time when it was a much more conservative company than it is today. Now IBM is one of the leading companies on GLBT diversity. As a closeted gay person in corporate America, I got to see how people reacted to gay people, so I had a perspective on how I thought they needed to be communicated with in order for them to understand gay issues. I also knew that companies were beginning to reach out and work with GLBT groups, but they needed to understand how to do it. And GLBT groups needed to understand how corporations operated. There was this need to bring the two together. Our first corporate client was American Airlines ten years ago, and we still have them as a client. But it was bringing together our knowledge of the community, our expertise on communications, our knowledge of marketing to take what was at the time a challenge for them and turn it into an opportunity. It was a very significant public relations challenge that now has lead them to be the marketing leader.

MW: Were you working with them after the incident when a passenger who had AIDS was removed from a plane?

COMBS: Yes, we were hired after that incident. The company had been doing a lot of good things, and yet they were still stumbling. They reached out to say, help us understand what we’re doing wrong. Bob talks about how we are a values-based firm. We only work on projects that meet the value systems of us as owners and us as a company. If the company isn’t sincere in wanting to fix the problem, whether it’s a gay and lesbian issue, an environmental issue, or a disability issue, we won’t work with the client because it affects our reputation.

MW: Have you ever dropped a client because their values have changed?

WITECK: We haven’t dropped any, but we haven’t accepted some. We feel strongly that there are certain issues that we shouldn’t work on — things that are hostile to civil rights, broadly speaking. Tobacco clearly is one that we’ve ruled out. We have to feel, as Wes is saying too, that they’re in sync with how we believe. Even if we stayed small forever, that’s a very good thing because you have control of your destiny. You can say, as Wes and I have, that we won’t do certain things we don’t want to do, and know that we can still make a good living working on things that we really care about. And so that’s where we find ourselves ten years later, on that same path.

COMBS: Money is not a motivator for the two of us. I’m not saying that we don’t want to make a nice living, but we would rather take on a project where we would be able to change the world and make it a better place because of our work, than tell the world that this widget exists. We have corporate clients on our list, and with very few exceptions they are tied to a particular issue. We wouldn’t do traditional corporate PR because we’re not in the best position to do that.

WITECK: I just want to mention that there are so many people in the communications field who good people too. I don’t want to feel sanctimonious that we’re the only ones who are white hats, because there are a lot of great white hat people. But as a small firm we just get to choose and focus on how we want to do that work.

COMBS: And we’ve stayed that way. The biggest change from ten years ago is that we’ve pretty much narrowed our focus into three areas: gay and lesbian marketing and public relations; health and disability; and what we call our Washington, D.C.-based community clients, who need to tap into the Washington media and reach out to this market specifically.

MW: You both have talked about being Democrats. When you started ten years ago, it was at the beginning of the Clinton era. Now you’re in what is in many ways a three-branch Republican town. How has the political shift affected your business?

WITECK: It’s not affected business, it’s affected our feelings. We wake up every day and hope that the nightmare goes away. [Laughs.] Wes and I have lived here forever, so we have many, many close friends who are Republicans. We don’t have a partisan focus on how we deal with our work. We deal with people of all kinds, we have to work with everybody. One of my close friendships is with Charles Francis, who heads up the Republican Unity Coalition. I respect what he does, and I think it’s invaluable. I have quarrels with some of the political topics that he and I get into, but that’s Washington.

COMBS: Because we’re not a public affairs firm per se, and we’re not a lobbying firm, we’re not as dependent on the shifts in the political climate. On gay and lesbian issues, having a more conservative administration is in some ways beneficial to us. There’s more of a need to communicate effectively. That’s why we have tied ourselves to a research company, because there’s a lot of emotion involved in gay issues. We’ve found that to be most effective with audiences that aren’t traditionally comfortable with talking about gay issues, providing the facts first helps the conversation go a lot further, instead of having that conversation tap into their emotional connection to the issue.

WITECK: There’s no question that corporate American probably looks a lot more Republican than we do. Nonetheless, we are finding ways to communicate. You can combine your business intuitions and knowledge with your activism and beliefs and you can make change that’s positive.

COMBS: Being pragmatic is a key to success. Certainly, there are people who succeed in being on the far left and being on the far right, but the world is very small over there.

MW: Was there any point where you thought maybe this business wasn’t such a great idea?

WITECK: Never. We’ve never had a contract or signed a partnership agreement, so for over ten years we’ve relied on each other’s boundless trust. And I have to tell you, we’ve had heartburn over a number of things. We’ve had knock-down fights yelling at each other a few times. But what’s amazing to me is that I never worry about this business partnership and friendship. I don’t know anybody else who can say that, I really just don’t. I don’t know how we were so lucky. [Laughs.] You’d better have the same answer.

COMBS: It’s true, we’ve never memorialized our agreement — we just started running and never looked back. There’s never been a time when I’ve wanted to call it quits. There’s something incredibly motivating and inspiring about this work. I got a chance to go back to IBM two years ago for a GLBT executive leadership conference that brought together 150 GLBT employees from around the world. I was one of the session leaders for the conference. Here I was, a former employee who wasn’t out at work when I was at IBM, who got to come back and teach at a facility that I only dreamed of going to when I was an employee. Now I was helping to enrich the lives of GLBT employees at IBM. My whole professional life came full circle for me in a way that I never would have predicted.

You see that all the time when people want to come interview here. “Oh my god, I want to make my life better.” “I hate my job as a lawyer, a salesperson.” “I want to give back to my community.” We hear it all the time, and we feel pretty lucky that we were able to do that and figure out how to make that work into a business and sustain our livelihood in the progress.

MW: You mentioned your research partner, Harris Interactive, and you do a lot of work about who gay people are as a community. Very often, groups that advocate against gay and lesbian legislation such as employment protection cite marketing studies that show the community as wealthier than the average heterosexual. I want to get a little bit of your feeling about the political pitfalls of the interpretation of marketing data. Are we rich, are we poor, are we middle class? How are we cutting the data?

WITECK: That’s why we actually started on that road [with more research]. We were so offended by poor marketing research, by poor sampling techniques, and by the myth of gay affluence. If you did the research properly you’d probably get a truer and more authentic view of who gay people are. A lot of the earlier research skewed toward that affluent, urban gay male. And they exist, you can’t discount them — for some marketers that’s exactly their customer. We are grounded by demographic research and have come to pretty much the same conclusions that most social scientists have: that politically and socially the gay community is a polyglot. They are rich and poor, young and old. They look like Americans. So when you review the body of the work we did in the last four years with Harris, it tells a more complex story. For those who tend to distort things, they don’t find any friends or allies in our work, and we think they never should.

COMBS: That’s a key thing. We are constantly having to correct those assumptions and misinformation. So data is like the gospel to us.

MW: It took many years for telephones to become ubiquitous enough to be a valid collection tool for polling data. Harris does a lot of research through online surveys. Have we gotten to a point where online access has penetrated far enough within the gay and lesbian community for research purposes, or is there the potential of people being missed?

WITECK: There will always be that concern. There is sample bias in all collection methods. The problem has always been the cost of telephone sampling and the low incidence [of GLBT respondents]. If you go door to door, the number of GLBT responses is like one percent; if you do it by phone it’s around 3 percent or less. Online you have more anonymity, so we do have confidence that we’re getting more people. Now the skew of course is that they’re online people. Propensity weighting is their technique to address that. They do hundreds of parallel [telephone] surveys a year. The Harris test has been up against all the pollsters, online and offline. In the 2000 presidential race and they got the results most accurately of all, compared against all methods of sampling.

COMBS: With call waiting, “Do Not Call” lists, and call blocking, doing telephone surveys is no longer a guarantee that you’re getting any better data than you’re going to get anywhere else.

MW: As people get more technology such as caller ID and savvier about data collection, where does that leave demographic research as people block off more and more avenues for people to actually reach them?

COMBS: Online is the future for us. The telemarketing controversy alone has so turned off people to responding at all to any calls. So I think the online is the future, and it’s imperative for all of us to get it right. And for gays, we have no other means of collecting data that is going to be as cost effective as doing it online. Also, GLBT people haven’t really been asked their opinions before, so I think they’re hungry to answer questions. They want to express their opinions, they want to tell people what they think.

WITECK: With online surveys, GLBT responders are quite a bit faster than anyone else. They’re so eager to be asked. We’ve been stigmatized, ignored and alienated for so long, and all of a sudden somebody says it matters what we think.

MW: Many GLBT and AIDS organizations have faced financial crises in the past few years. Is this something that you’re seeing with a lot of your non-profit clients?

COMBS: Our work goes beyond the gay community — we work with a lot of non-profits. For example, we represent the Christopher Reeve Paralysis Foundation and we do a lot of work with them in message development because they compete with a lot of other health care issues that in some ways are perceived to be more immediate and more critical than paralysis. There’s always a need. I think that the challenge that an AIDS organization faces in our community is how do you make this idea fresh and relevant to people who have become in some ways desensitized to the issue? Some of it’s due to the medications have made people who have HIV and AIDS not as visual in our community — we don’t see it as often.

There’s a whole generation that really didn’t know anything about HIV and AIDS, and what they know today is certainly not what we experienced. The models that got people like Bob and I to come to an AIDS fundraiser were largely due to people that we knew who were dying. This generation doesn’t have that reference point. But that doesn’t mean that they don’t care. The key is to be able to tap into those people in a way that is relevant to them.

MW: We’ve talked a lot about how things were 1993 and how they’ve changed in the past ten years. How do you predict things will have changed ten years from now?

COMBS: I used to refer to Ellen’s coming out in 1997 as a pivotal moment in our history. More happened for GLBT visibility in that one year of discussion about her coming out than perhaps had happened in the ten or fifteen years prior in our movement. This last year has eclipsed that moment ten times. The Supreme Court sodomy decision, Canada’s marriage decision, this popular culture television phenomenon with Queer Eye and Boy Meets Boy, the discussion in the Episcopal Church. There’s discussion of GLBT issues everywhere.

Survey research that we just conducted says that a majority of Americans support a lot of rights and benefits for gay and lesbian people, yet they don’t like the word marriage. They’ll give them almost everything else as long as they don’t call it marriage. I am immensely confident that what is happening in corporate America on GLBT equality in the workplace will translate to the public policy arena, and the communities that we live in will more reflect the places that we work.

WITECK: In the last ten years, our business in the community has been very much based on identity. I think in the next ten years identity will become much more diffuse. Younger people clearly are re-labeling their identities sexually, in more profoundly nuanced ways. They’re not trying to be pigeonholed or say that they are one thing now and forevermore. Ten years from now it’s going to be hard to have a gay-centric identity. I think it’s going to be more of a generational change in terms of understanding about people. Young people are more and more like gay people in terms of their openness about things, about not wanting to be pigeonholed or stereotyped or marginalized.

Ten years from now we’ll have had such major sea change that I think legal marriage will be a reality. The matter-of-factness of it will change things dramatically. I’m old enough to recall when African Americans first started appearing in advertisements. That was a huge deal for a lot of people. But along the way, those things that were so big at the time became matter-of-fact. A lot of people rue the day when that happens, because then we’ll be part of the larger community. But that’s where we’re meant to go.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!